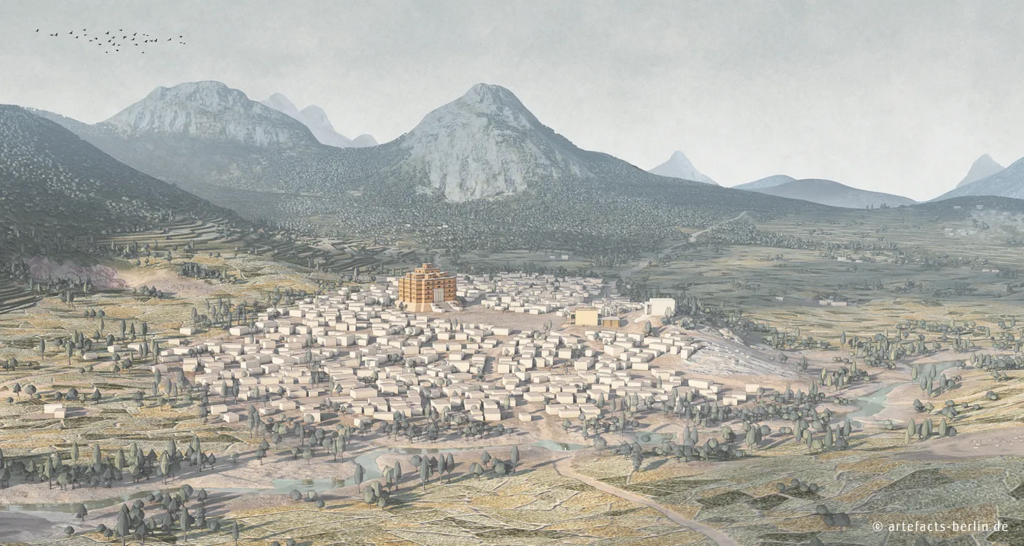

Yeha, the capital of an ancient kingdom in the first millennium BC, was home to a grand palace, a large temple—partially standing to this day—and a necropolis that offers us insight into the past.

Introduction

After the second millennium BC, references to Punt largely disappear from historical records. However, civilisation in the northern highlands of Ethiopia and Eritrea continued to endure, gradually adopting new characteristics. Contact with South Arabia increased, particularly from the latter half of the second millennium BC, as South Arabian polities began to take greater interest in the region and likewise the polities of the highlands recouped some of the losses from a loss of Egyptian trade. Thus interaction intensified, especially through merchants, some of whom settled and intermingled with the predominantly Cushitic population, giving rise to a partially Semitic-speaking community.

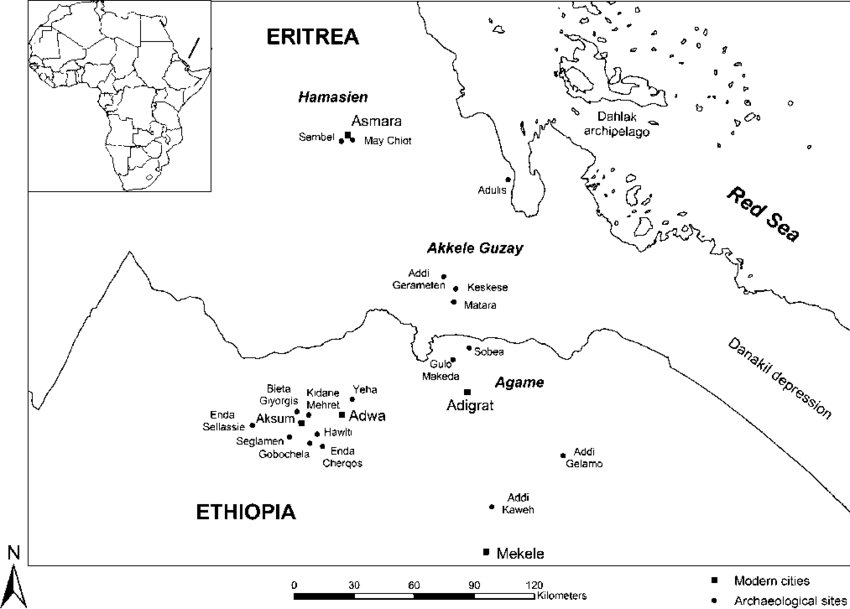

By around the 8th century BC, new polities began to emerge across the highlands. One of the most prominent was Yeha (ይሐ), located in north-central Tigray, Ethiopia. Dating back to the early to mid-first millennium BC, Yeha’s significance is evidenced by its remarkably preserved structures and artefacts. These structures reflect strong architectural and cultural similarites with the Sabaeans of South Arabia, while also displaying distinct features indigenous to the region.

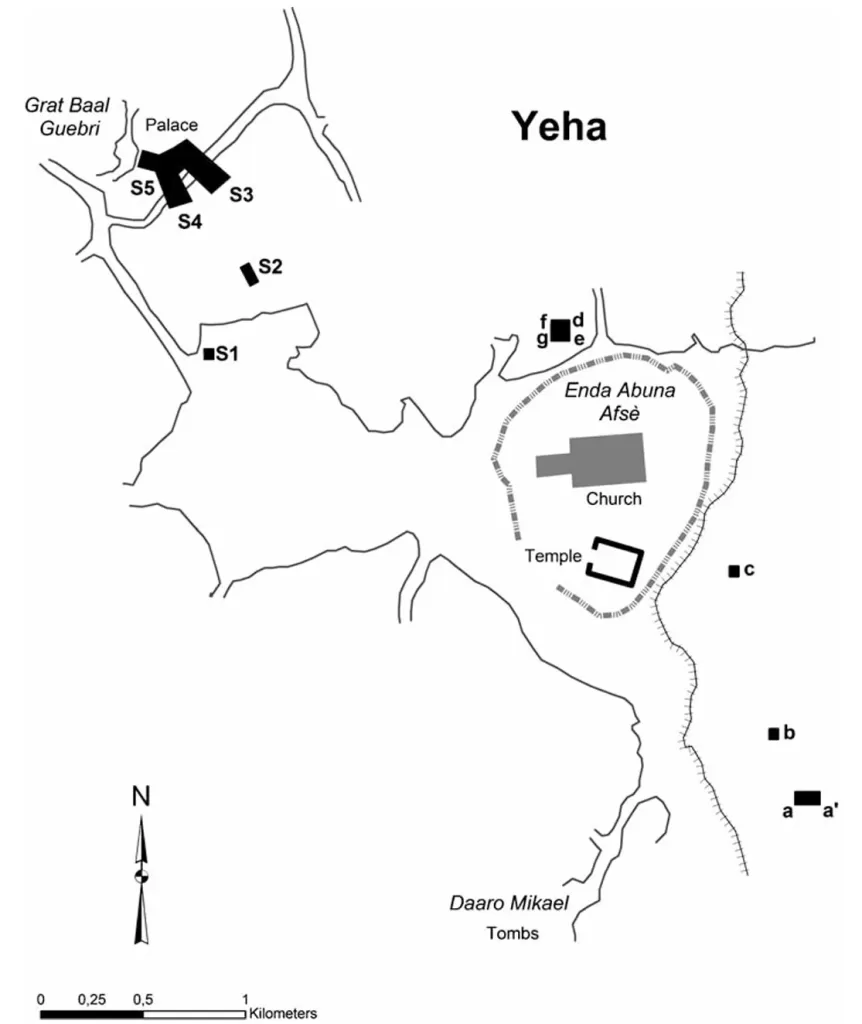

There are three significant pre-Aksumite structures/sites located at Yeha:

- The Great Temple of Yeha

- The Palace at Grat Be’al Gebri

- The Necropolis at Daaro Mikael & Abiy Addi

The word Yeha comes from an inscription found at Addi Akawah, in Tigray (close to where The Great Temple is located), this inscription refers to a great temple named Yeha. The inscription roughly reads as follows:

/

The Great Temple of Yeha

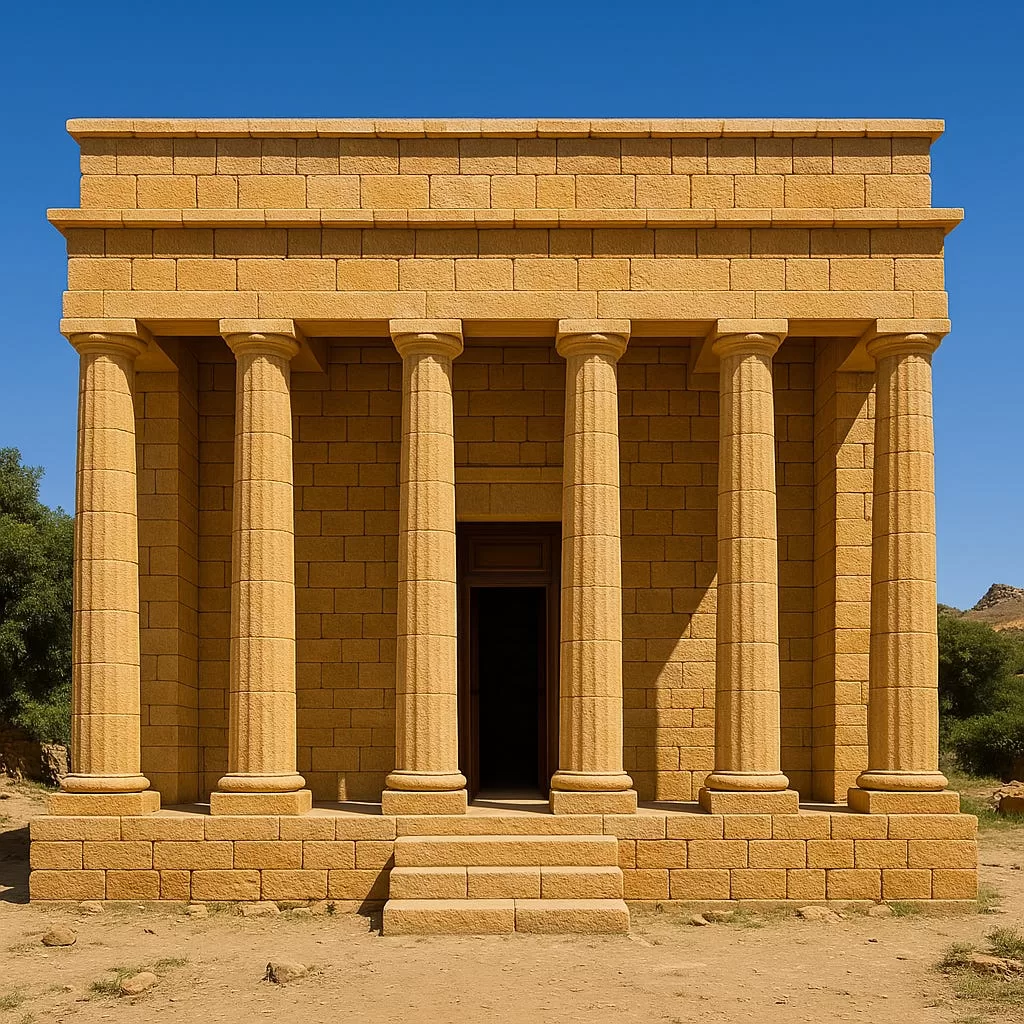

The Great Temple was once a significant centre of worship, it’s currently the oldest remaining megastructure in the region. It uniquely mixes indigenous architectural styles and south arabian. Its main purpose is deemed to be a place of worship for the god Almaqah1, which was the southern Arabian moon god.

Although researchers initially estimated the temple’s age to be 500 BC, it has since been revised to 800 BC2. Before the creation of the temple, a settlement is thought to have existed in the surrounding area.

Almaqah is associated with the Ge’ez word “ኣምላኽ” (ahmlak), which means “god” and is still used in modern Tigrinya and Ge’ez. This is likely because the original word was adapted during the conversion to Christianity in the 4th century AD, which coincided with the Aksumite period.

Excavations

Extensive archaeological excavations have revealed much about the temple’s structure and history. The Great Temple, owes much of this to its current preservation to it’s function as a church dedicated to Abba Aftse. This adaptation, believed to have occurred around the 6th century AD, not only preserved the structure but also integrated it into the ongoing religious practices of the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian community. Even now the temple hosts major annual religious festivals, highlighting its continued significance as a sacred site3.

Numerous foreign travellers such as the Portuguese explorer Alvares, who visited Yeha in the early 16th century AD, noted the ancient structures existence:

Architectural Features

The actual structure spans 18.6 x 15.0 m and with a height of up to 13 meters high 4, the walls consisted of rectangular blocks of sandstone. The Great Temple originally featured a large porch at its west that extended over 5.1m5 with six rectangular pillars, a design element that finds parallels in structures in southern Arabia. From the entrance, the double wooden doors opened to reveal a narrow passageway leading to the temple6.

The structure features a ground floor and evidence suggesting the existence of a second floor. The interior dimensions are 12.6m by 11.3m, comprising a central nave flanked by two sides, each with two aisles separated by square pillars (totalling five aisles). An inner drainage system, likely used to channel water runoff outside, is also evident. At the rear of the temple, a stepped entrance leads to three rooms7.

These ibex carvings, now located at the nearby church in Yeha, may have originally been on the temple itself8.

Grat Be’al Gebri: Elite Architecture

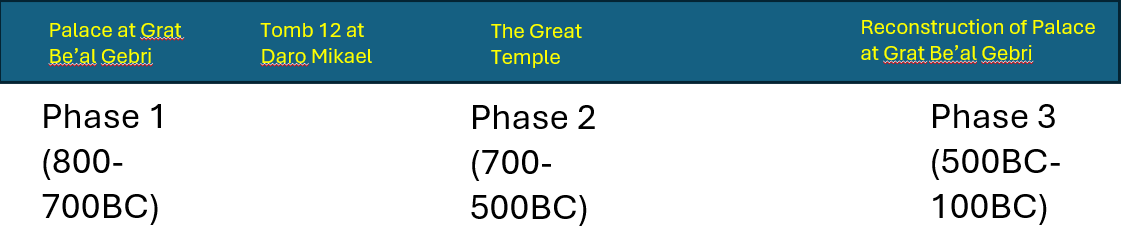

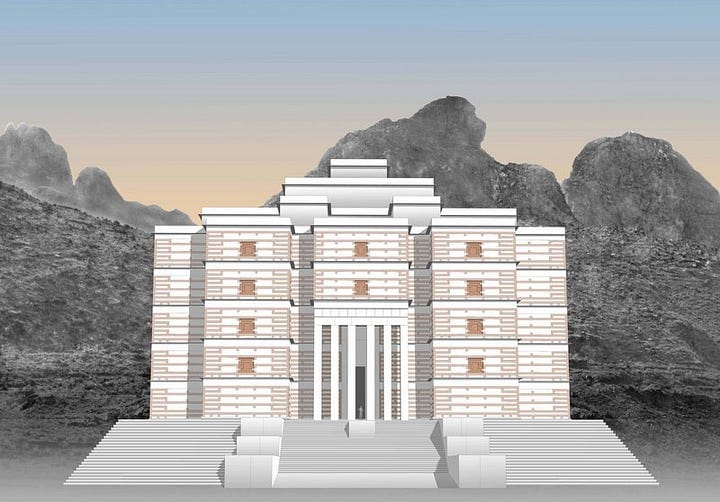

Another significant discovery at Yeha is Grat Be’al Gebri, often referred to as a ‘palace’. The structure likely served as a residential and administrative hub for the ruling elite. Archeologist Francis Anfray has dated the structure to between the 5th Century & 2nd century BC9.

Prior to the construction of the palace, an earlier structure existed10.

Architectural Features

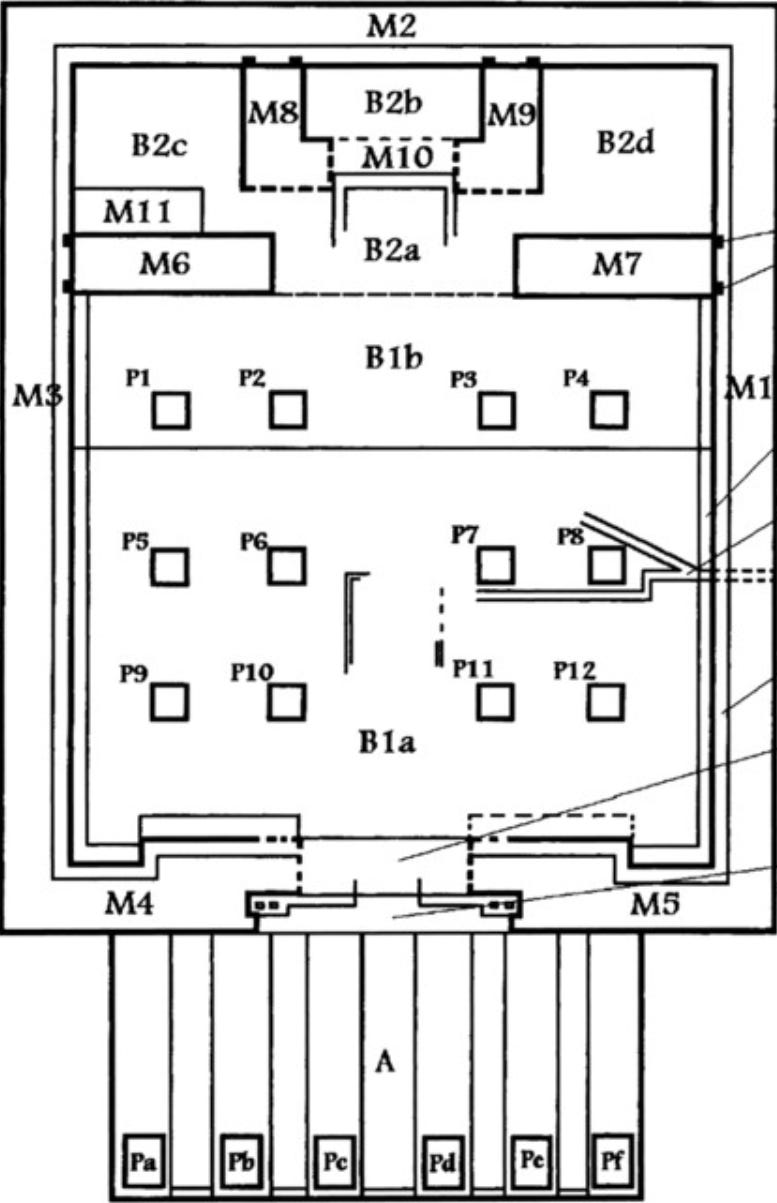

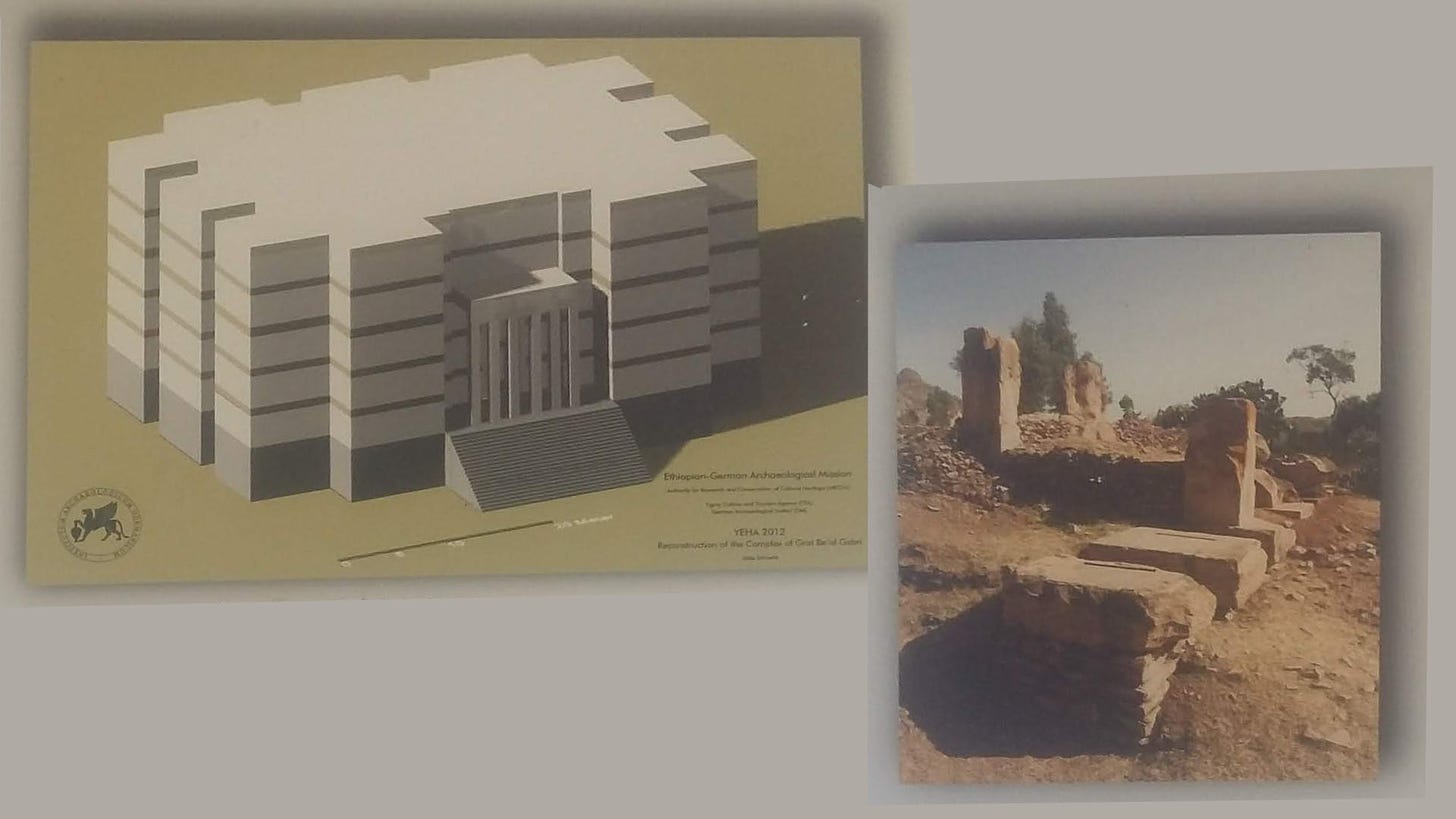

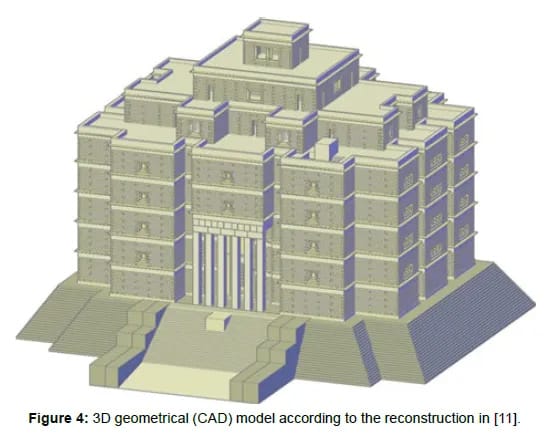

The building originally spanned at least 46 x 46 meters and included a 4.5-meter-high podium, This podium housed an interior chamber system11. It was constructed primarly from timber & locally quarryed stone12.

The primary entrance was marked by a six-pillar roofed porch, the bases of which, along with some pillar remnants, remain today. Behind this grand entryway lay a large gate leading into a hallway, which in turn opened into a corridor that bisected the building. This corridor provided access to various rooms, although the specifics of these rooms remain less documented due to the building’s deteriorated condition13.

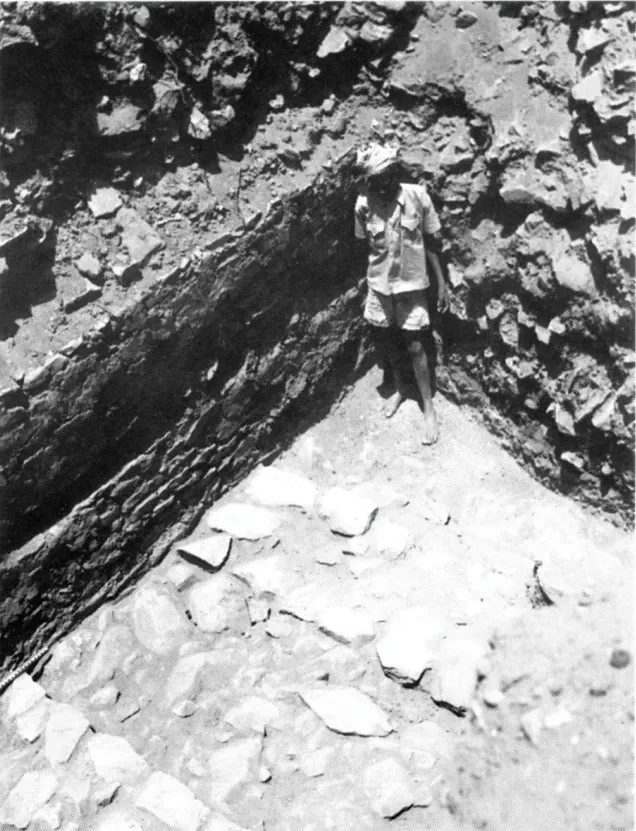

Grat Be’al Gebri, showcases two principal phases of construction, each illustrating different architectural techniques and cultural influences. Initially, this monumental building was erected with a distinctive South Arabian influence, featuring a stepped podium and a front porch supported by pillars. Unfortunately, this initial structure met its demise through a catastrophic fire, leading to its destruction14. The earliest section of the building is the outside staircase entrance, which is estimated to be dated to around 750 BC-500 BC15. This staircase had more than 24 steps16!

Subsequently, a second building phase ensued where a new structure was built directly over the ruins of the first. This new construction utilized rougher wall techniques, possibly incorporating the Aksumite ‘monkey-head’ technique, known for its timber framing and use of rubble stones and mud. Stratigraphic test pits at the base of the podium further revealed that the site had been occupied even before the construction of the original building17.

Grand multi-story buildings like the one in question were present during the Aksumite times, as well as in later periods such as the Zagwe period & the Solomonic era. This particular structure could have been the first elite building created in the region, and it might have served as a palace for a ruler or king of that time.

Other Artifacts found

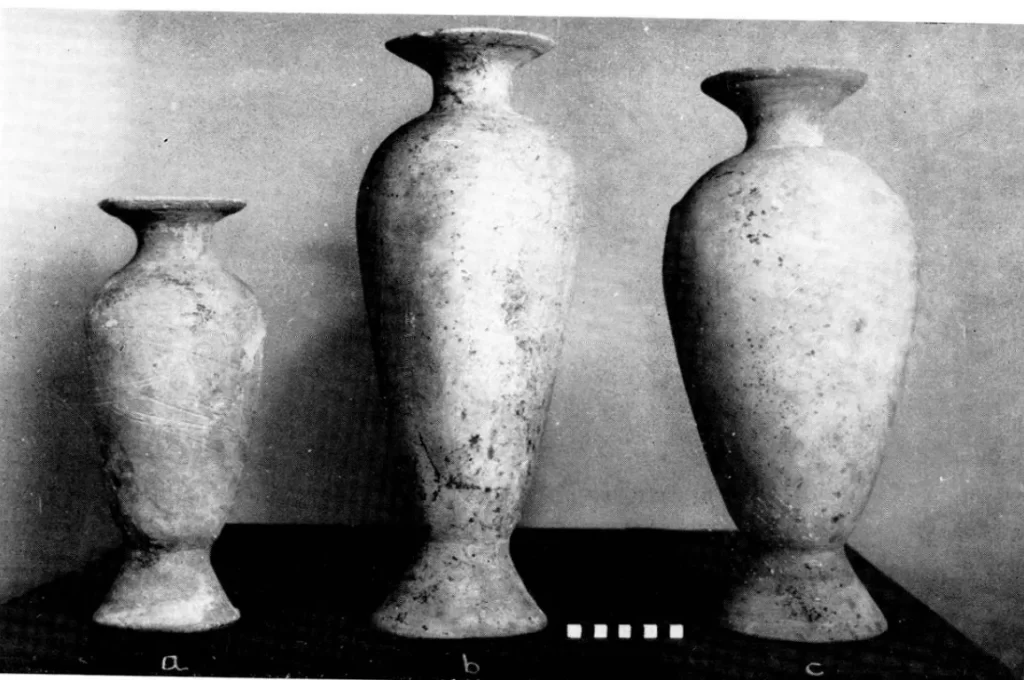

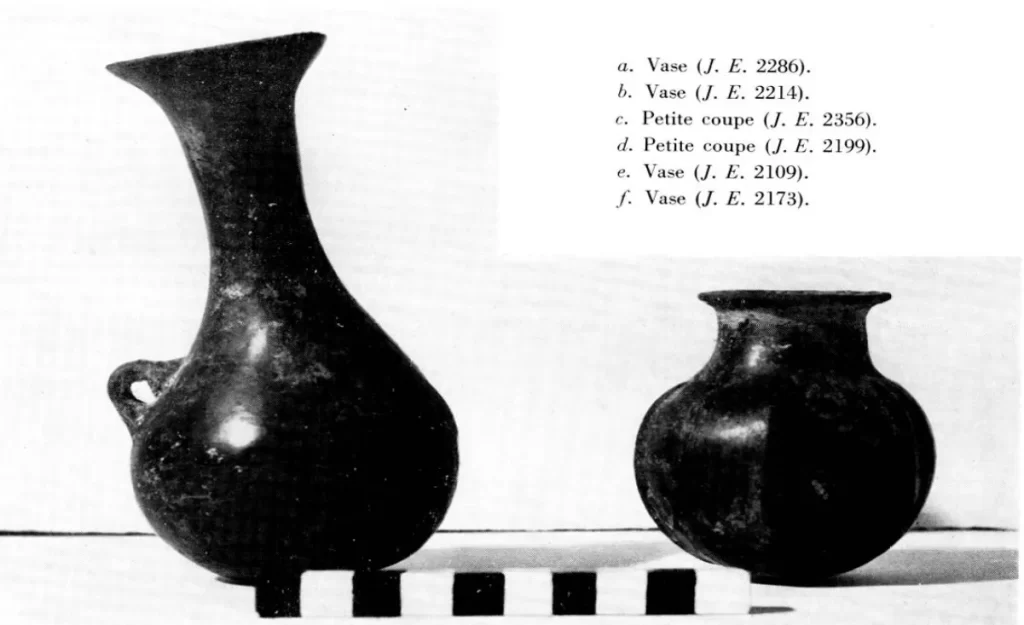

Excavations and tests in areas surrounding Grat Be’al Gebri have yielded a range of artifacts. Notably, ceramic findings from the second phase of the building’s use include a variety of wares such as red coarse ware, black polished coarse ware, and several types of fine wares, reflecting the rich material culture of the inhabitants.

A remarkable discovery was a statue of a woman dressed in traditional cotton attire resembling a modern-day Kemis. Nicknamed the “Queen of Yeha,” it was found at the nearby Pre-Aksumite archaeological site of Hawelti and dates back to that era.

Could this “Queen of Yeha” be connected to the Queen of Sheba? While it may seem far-fetched, the dating of this period, along with Yeha’s Sabaeic influence, suggests the possible existence of a prominent queen during this era—one whose legacy may have later evolved into the Queen of Sheba narrative found in the Kebra Nagast.

The Necropolis: A Glimpse into Elite Pre-Aksumite Burial Practices

Adjacent to these monumental buildings is the necropolis, a large burial site at Daro Mikae, where tombs of the elite have been uncovered. The artifacts and tomb constructions found here highlight a society that placed significant emphasis on the afterlife and its preparation, especially for elites.

Professor Rodolfo Fattovich suggested a date for these tombs around the mid-first millennium BC, with evidence of continued use into the late first to early second millennia AD18.

It is believed that the tombs found in Yeha were used for the rulers of the surrounding areas, maybe even the elusive D’MT kingdom. It is interesting to note that similar subterranean tombs were also used for Aksumite rulers at Aksum. This suggests that the practice of building such tombs may have originated in Yeha and spread to other regions.

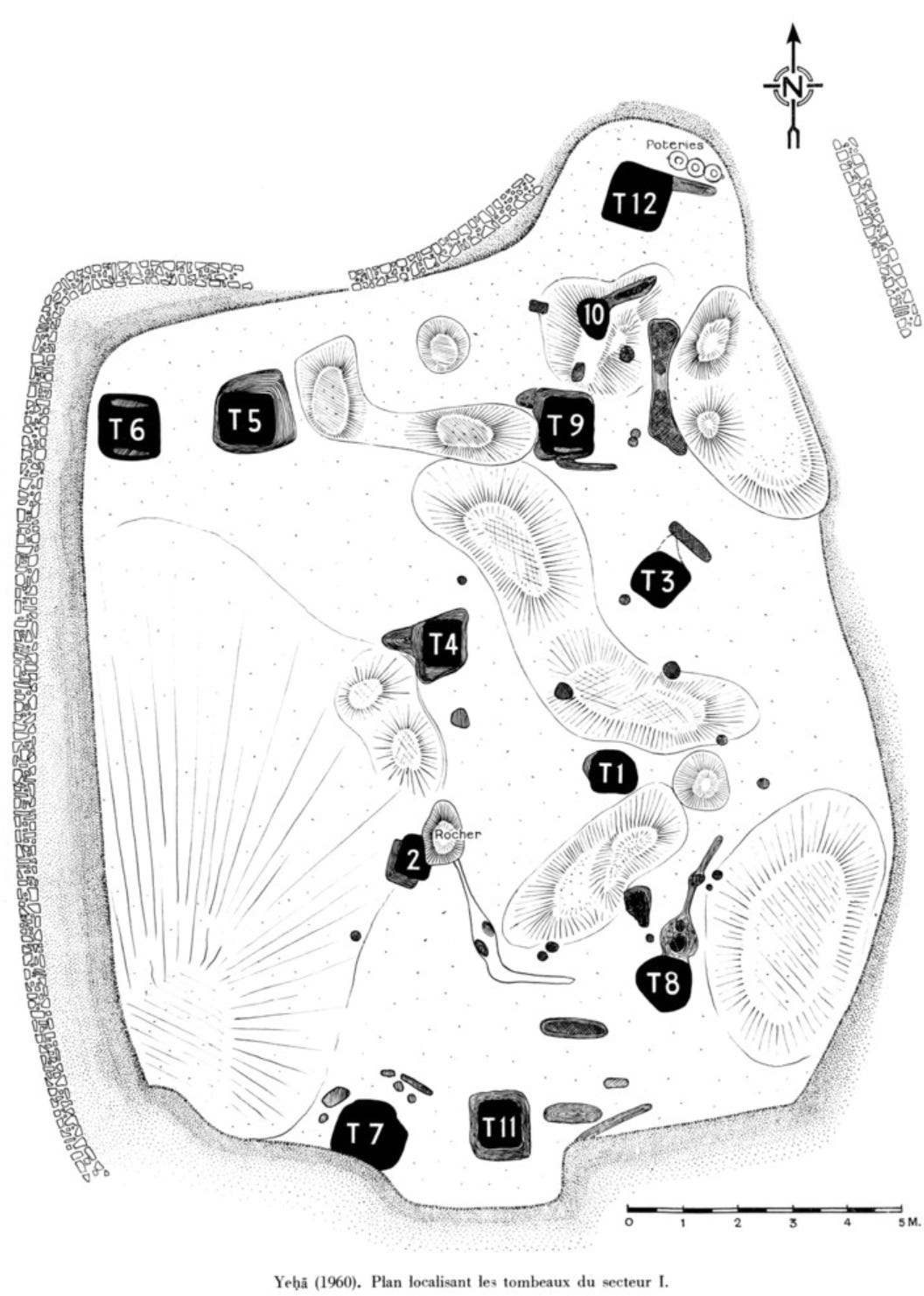

Daaro Mikael

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Ethiopian Institute of Archaeology, led by archaeologist F. Anfray, conducted excavations at Daaro Mikael, located at the Necropolis south of Yeha. The team uncovered seventeen tombs and two burial chambers, most of which contained various types of pottery and artefacts, with some even holding skeletal remains19.

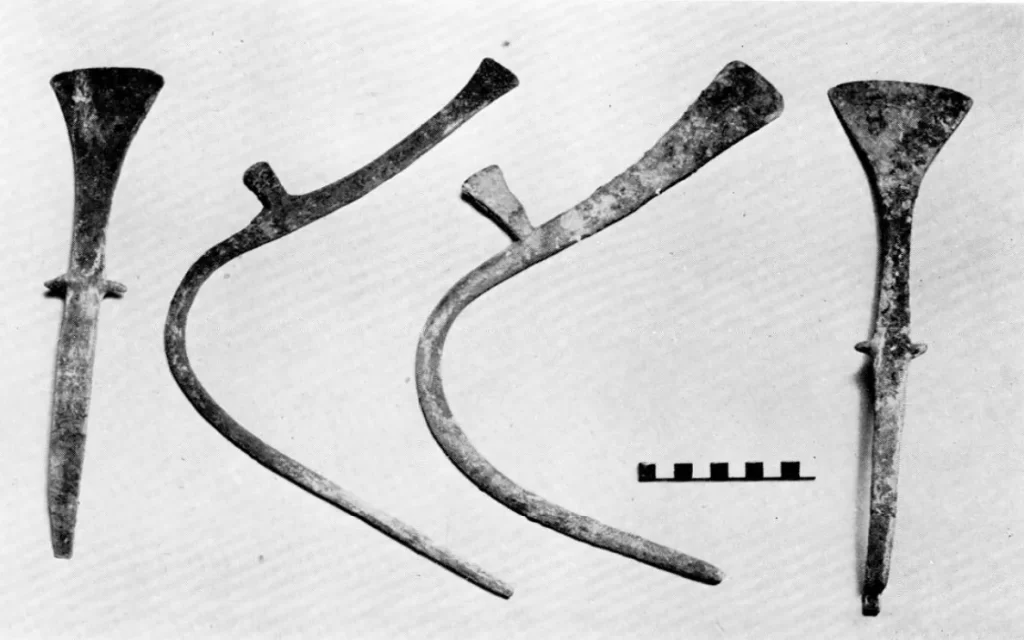

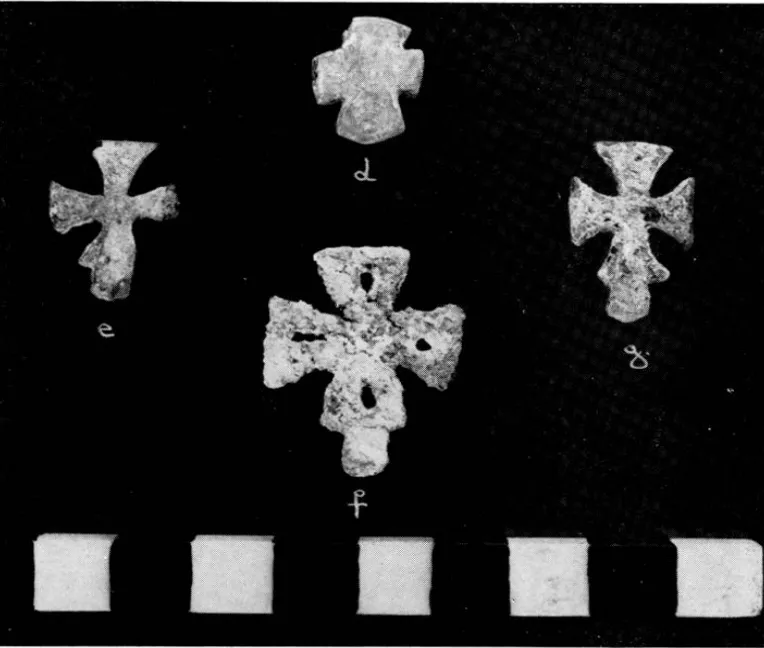

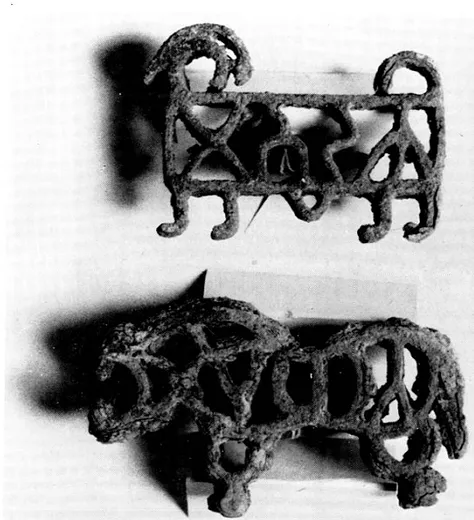

These artefacts included storage vessels like large vases for holding grain, cauldrons for cooking, and early forms of jebenas used for brewing coffee. Other items found included tools for cutting wheat, bracelets, necklaces, incense burners, and objects from later periods, such as crosses.

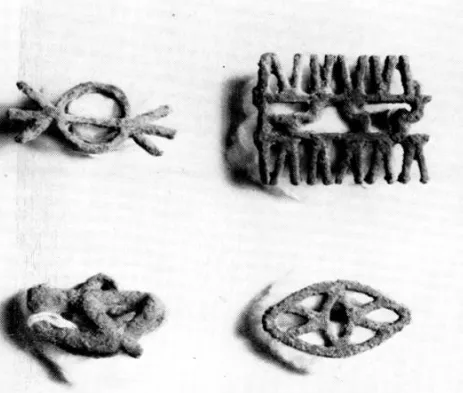

One of the artifacts discovered, were bronze seals, some of these featured Sabaen scripts and motifs like ibex which was associated with the god Almaqah, however, they also included indigenous elements not seen in southern Arabia. This blend is unique indicating a localized adaptation of external influences20.

Abiy Addi,Yeha

In the autumn of 2009, a joint Ethiopian-German archaeological team conducted a survey in the area of Yeha, specifically on the hill slope of Abiy Addi, located opposite the ancient Yeha settlement. This survey led to the discovery of a necropolis with visible signs of burial sites, Local residents shared with the team that one of the tombs contained a shaft and a staircase, indicating the presence of subterranean burial chambers21.

Further excavation in the spring of 2010 revealed six rock-cut tombs, each featuring a 2.5-meter-deep vertical shaft of rectangular shape, with one grave chamber at each of the narrow ends. Chambers of various sizes were also found, some extending up to 4 metres in length and 1.2 metres in height. The entrances to these chambers were originally sealed by rectangular stones, though most were missing by the time of discovery.22.

Interestingly, rock-cut tombs of this type appear in the archaeological record of Yeha before similar structures were found in South Arabia, suggesting that such burial practices were indigenous to the region before the rise of the Ethio-Sabaean kingdom23

Brief Timeline Of Events & Interaction with Periphery states

Pottery resembling the style found in Yeha, initially found mostly in local areas during Phase 1, expanded in distribution during Phase 2. This expansion included not only sites in Tigray but also in Akkele Guzay, suggesting increased interaction and cooperation between the populations of these regions. In contrast, the ancient Ona sites in Asmara preserved their unique ceramic traditions, though fragments of Ona jars have been discovered in Akkele Guzay and Tigray. This indicates that trade was possible, however Ona sites likely had their distinct culture and possibly their own elites24.

Besides Yeha, around the mid first millennium BC, Adulis and it’s adjacent port of Gabaza & the towns around it, were probably the only comparable area’s of urban society at the time. It’s likely that during this time many different polities existed in the highlands of northern Ethiopia & Eritrea, whether Yeha was a part or even the capital of one of these polities, particularly D’MT is questionable, no archeological remains have been found at Yeha that directly state D’MT (all inscriptions directly mentioning D’MT were found near Aksum and in Eastern Tigray25), however whatever the name of the polity that controlled Yeha during this time, it generated considerable revenues and had a organizational structure complex enough, to construct several great works of art.

Conclusion

Yeha is one of the most famous and researched sites from the pre-Aksumite period. It features several notable sites and was likely one of the capitals of development during the 1st millennium BC. Unfortunately, not much archaeological work has been completed in the region, so many questions remain unanswered. However, new discoveries are guaranteed to occur, and our knowledge of the area is still in its infancy. It’s clear that Yeha was one of the first signs of hierarchical societies in the horn of Africa, with organized places of worship, habitation and burial.

Bibliography

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 24 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 26 ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 147). ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 24 ↩︎

- Ancient Churches Of Ethiopia, pg 35. ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 148). ↩︎

- Ancient Churches Of Ethiopia, pg 35. ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 26 ↩︎

- AXUM, by YURI M. KOBISHCHANOV. Pg 11 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 26 ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 150). ↩︎

- https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/preliminary-structural-analysis-for-the-archaeological-reconstruction-of-the-ancient-palace-grat-beal-gibri-in-yeha-ethiopia-124381.html#:~:text=It%20is%20the%20palatial%20administrative,survived%20apart%20from%20the%20podium. ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 151). ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 278 & 279) ↩︎

- Ancient Churches Of Ethiopia, pg 33 ↩︎

- YEHA. LES RUINES DE GRAT BE’AL GEBRI. RECHERCHES ARCHEOLOGIQUES, pg 7 ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 278 & 279) ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- F. Anfray 1963a. Une campagne de fouilles à Yéha), CLIV ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 153). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 153). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 285) ↩︎

- Foundations Of An African Civilization, pg 38. ↩︎