By the early 11th century AD, the Zagwe Dynasty had risen to power. The exact origin of the name ‘Zagwe’ remains uncertain. As discussed in the “Fall Of The Aksumite Empire” article, one theory suggests it derives from the Ge’ez word ዘአጒየየ (zaagwayaya), meaning “he who ran/pursued.” Referencing the founder, Mera Tekle Haimanot, who reportedly pursued and defeated Dil Na’od, the last Aksumite emperor, by throwing a spear into his back during battle. Another possibility is that ‘Zagwe’ comes from ‘Agaw,’ reflecting Mera Tekle Haimanot’s position as a ruler of the Agaw people in the Lasta region, where the Zagwe Kingdom had its administrative centre1. A third claim suggests the name could be a shortened form of Zewge Michael, Mera Tekle Haimanot’s Christian name2. The Zagwe Dynasty would rule for over 250 years, ending in 1268/9 with its overthrow by Yekuno Amlak, who founded the Solomonic Dynasty.

The term “Zagwe” was not a self-designation used by the rulers of that dynasty; it was a name applied retrospectively, beginning around the 14th and 15th centuries AD3. Inscriptions from the period, including those from the reign of Emperor Lalibela, refer to the rulers and their people as the people of “Bǝgwǝna”4.

Emperor Mera Tekle Haimanot (~1010AD-1023AD)

Information on the Zagwe Dynasty is sparse, including details about its founder, Mera Tekle Haimanot, who I believe began his reign around 1010-1023 AD5, (A traditional loyal lineage states him to have reigned for 13 years6). Not much is known about his reign, most of his rule was probably spent consolidating his empire, both militarily and administratively. There may have been an influx of migrants from Fatimid Egypt, following a decree by Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, which permitted Christians in Misr (another term for Egypt) to freely travel to other Orthodox regions like Greece, the Nubian kingdoms, and Abyssinia. It is speculated that some of these migrants moved south into Nubia and Abyssinia, becoming artisans and scholars to avoid potential persecution in Egypt7. This information is supported by an analysis of the life of Patriarch Zacharias of the Coptic Orthodox Church, who served as patriarch between 1004 and 1032 AD8. The Excerpt is as follows:

Also during Mera Tekle Haimanot’s reign, it is evident from the interactions between Caliph al-Hakim and Patriarch Zacharias that Abyssinia under his rule did not persecute Muslims, rather they were allowed to practice their religion freely. The excerpt is as follows:

Whispers Of A Solomonic Origin

In the early 10th century AD, the first recorded association of Abyssinia with the Solomonic lineage was made by Patriarch Cosmas, who served as Patriarch between 920 and 932 AD9. Historian Sergew Hable Selassie suggests that the Zagwe Emperors were likely the ones who initiated the propagation of the Queen of Sheba myth10. However, their version of the myth differed from the later claims made by the descendants of Yekuno Amlak. Instead of focusing on a Solomonic connection, the Zagwe narrative revolved more around Moses. For instance, Emperor Lalibela himself propagated the belief that he was descended from the family of Moses11. The excerpt is as follows:

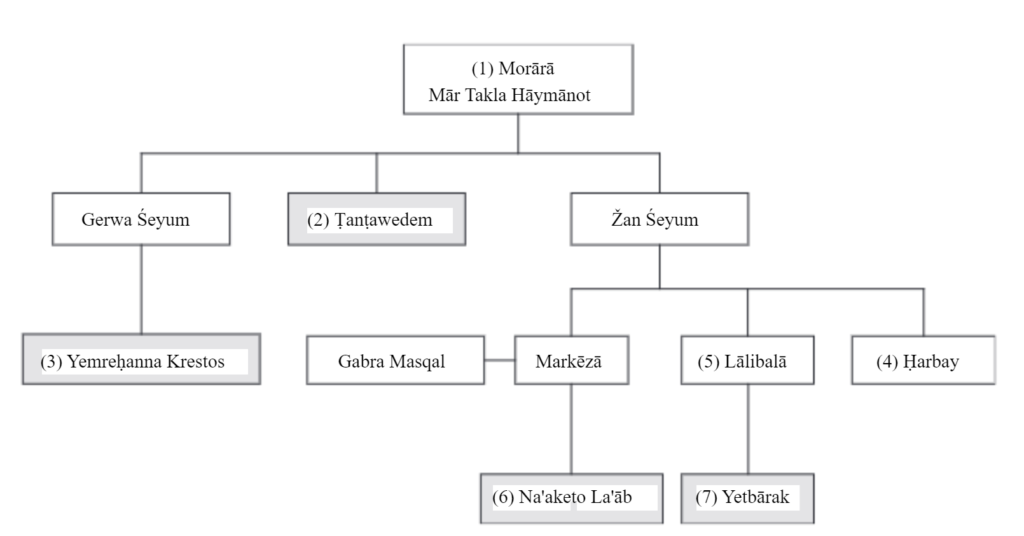

According to the Gedle Yimreh Kristos12, Mera Tekle Haimanot had three sons: Tetewudem, Girma Seyoum, Jan Seyoum. According to the manuscript Gedle Yared, he had died from an assassination attempt which, mortally wounded him in the stomach13, thus indicating discontent in the empire, and explaining his rather short rule.

Some scholars speculate that Mera Tekle Haimanot would be remembered as “Murara/Morara” by his predecessors…

There is an approximate 40-year gap between the reigns of Mera Tekle Haimanot and Tantawedem, during which sources for the Zagwe period are scarce, making it impossible to establish an accurate timeline. However, it is plausible that multiple emperors ruled during this interval. For instance, historian Sergew Hable Selassie notes that one of the Zagwe king lists includes seven emperors between the reigns of Mera Tekle Haimanot and Tantawedem14. He considers this list to be the most accurate, although we have little information about these other Emperors.

Emperor Tantawedem (1070-1090AD)

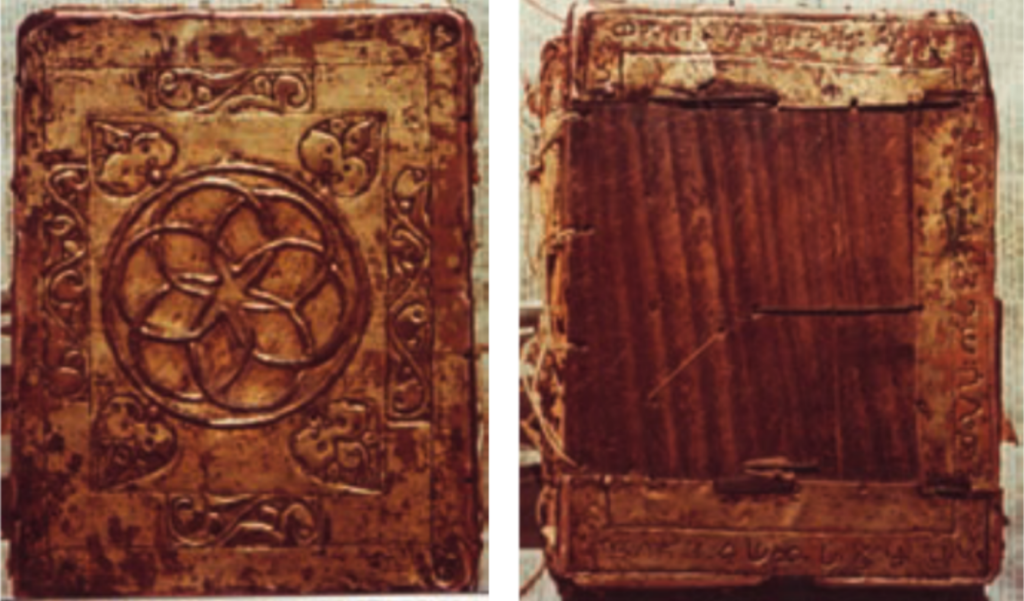

Engraved on this cross are the words: “I have acquired this cross (sign of the cross), I, Solomon the king, son of Murāra, and my name is Ṭanṭāwedem”.15 This inscription is particularly intriguing as it offers further evidence of the early formation of the “Solomonic Theory.” It is likely that during the time of the Zagwe Dynasty, the foundations of this concept were beginning to take root.

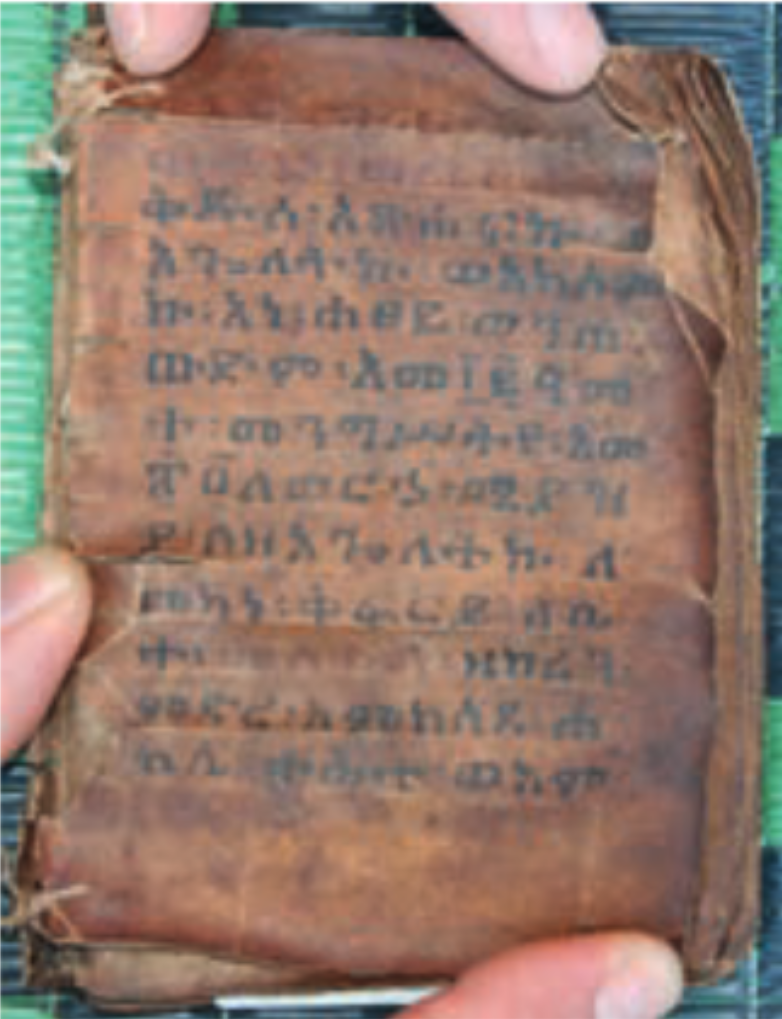

Upon the death of Mera Tekle Haimanot, Tetewudem (also known as Ṭänṭäwǝdǝm – baptismal name) ascended to the throne, bearing the titulature “Solomon, son of Murara”16, his regnal name was Solomon and his surname was Gaba Madhen17. Unlike his father, Tetewudem was less tolerant toward Muslims. This is evident from an inscription found on a manuscript that was donated to the church of Urā Masqal. The inscription mentions that Tetewudem seized the land, people, and livestock of several locations (unfortunately their present-day location is unknown) and donated them to the church. He also mentions an incursion into Serae (Eastern Tigray18, not to be confused with Serawe), specifically a place called “Sa Andewat” (location unknown) which was inhabited by Muslims however they were subjugated and their goods transferred and donated to a church.

The North

Tetewudem also issued a land grant for a church named Ura Masqal (Located in modern-day eastern Tigray), in which he explicitly warned several governing entities not to interfere with the lands bestowed upon the church19. He specifically addressed three Sayyumans (Governors), from Agama, Bur, and Sarawe. Notably, the grant also references a Bahr Negasi (Bahr meaning “sea” and Negasi meaning “king”), marking the first historical mention of this title. A document from the later Zagwe dynasty, during Emperor Lalibela’s reign, mentions that this Bahr Negus ruled over a kingdom called Mā’ekala Bāḥer20, it’s possible that the Bahr Negus also ruled the same land at this time.

The Inscription is as follows:

Several lands are mentioned, such as Sarawe, which is in reference to the region of Seraye in modern-day Eritrea,21 while Bur was a coastal province that spanned Akele Guzay, reaching up to Adulis22. Lastly, Agame is mentioned, this is an ancient area first mentioned in the Throne Of Adulis, it covered roughly the same area as the Agame region today. Additionally, the land of Gwǝlo Mäkäda is mentioned as being under the authority of several Sayyumans, likely referring to a region near present-day Agame23.

Scholars also hypothesise that Gwǝlo Mäkäda might have been a region covering the northern periphery, encompassing the shum of Sarawe, Agame and Bur24. This would then mean the Bahr Negus, was likely in charge of these Sayyuman, therefore Gwelo Makada could have been an earlier form of Mā’ekala Bāḥer.

It is likely that the Bahr Negus held a tributary status under the Zagwe Emperors, evidenced by the land grants given to northern churches such as Abba Libanos. However, direct control over the Bahr Negus’s territory seems improbable. The inscription above clearly indicates that the Zagwe Emperor was issuing a warning to the Bahr Negus, suggesting that the latter maintained a degree of independence and was not directly subject to imperial authority.

Debre Libanos Church near Senafe in Eritrea, a manuscript has been found, on the cover, there is an inscription that states the following: “I, King Solomon, had this Gospel cover bound for the church of Abbā Meṭā’ede ‘Aham.” – This is in reference to Emperor Tantawedem & Abba Metaéde Aham is referring to the Monastery of Debre Libanos25.

The Dhalak Islands (11th & 12 Century AD)

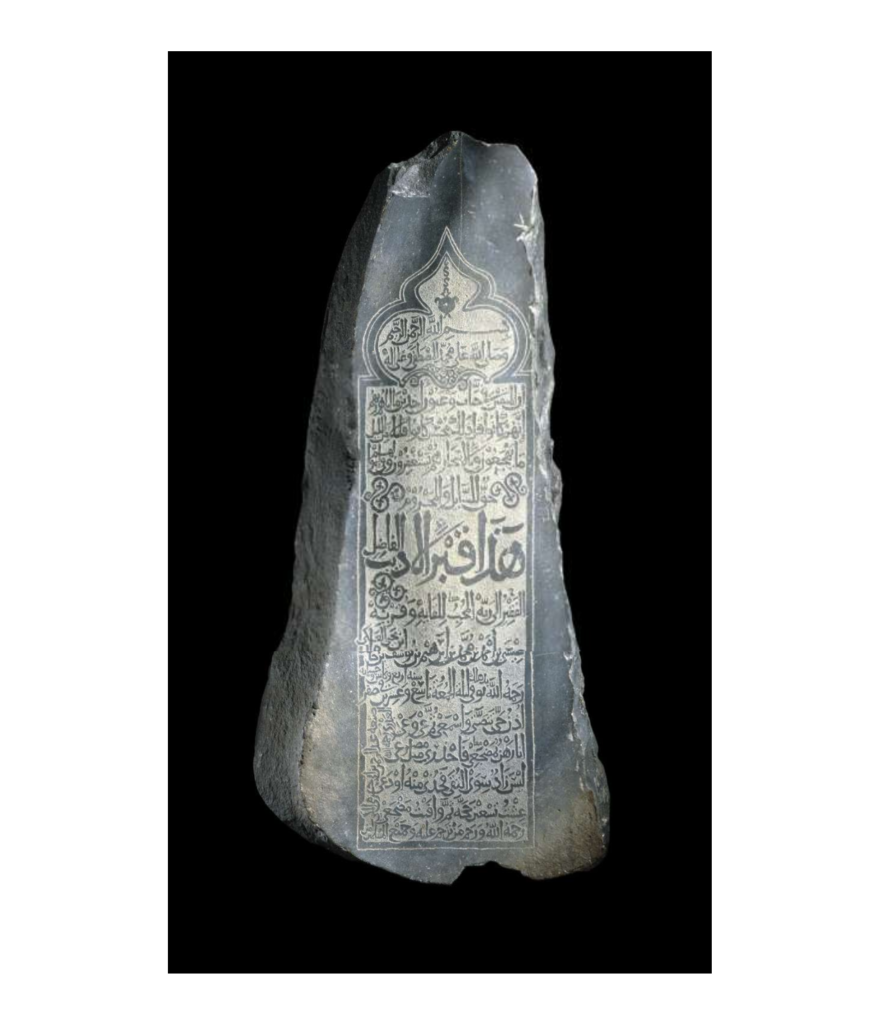

In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Dahlak Islands experienced a significant surge in trade, drawing merchants from across the Muslim world. This flourishing commerce led to the emergence of the Dahlak Sultanate, ruled by the Nagahid Dynasty—former Abyssinian slaves who had briefly ruled Yemen starting from around 1021/2226. The first known sultan to rule the Dhalak Sultanate was named Al-Sultan Al-Mubarak27 and was found in a stele erected and dated to 1093.

The Dahlak Sultanate’s wealth primarily stemmed from taxing trade ships traversing the Red Sea, whether they were journeying from the Indian Ocean to Egypt or vice versa28. The islands were prosperous enough to mint their own coins, and archaeological findings suggest that the inhabitants had connections with Qwiha in Tigray, as evidenced by the discovery of several funeral stelae in Arabic dating from the 10th to 13th century AD29. Qwiha was situated on a route close to and leading into the Afar depression where salt mines were located, making it an important stop for traders from the lowlands to meet with highlanders30. A Muslim community was attested to live alongside Christians and it was a route to Negash, Tigray where one of the first Muslim communities in the highland exists.

It appears that the prominence of the Dahlak Sultanate was short-lived, with its significance already diminishing by the 12th century AD31.

The growth of the Dahlak Islands in the 10th and 11th centuries AD likely coincided with a weakened Abyssinian state during the formative stages of the Zagwe Empire, when sea trade through ports was limited. However, as the Zagwe Empire later established control over Zeila, it expanded its trade capacity, diminishing the significance of the Dahlak Sultanate. Additionally, the establishment of the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt, which extended its control over Yemen from the late 12th century AD, brought increased stability to the region—a stability that had been lacking in previous centuries.

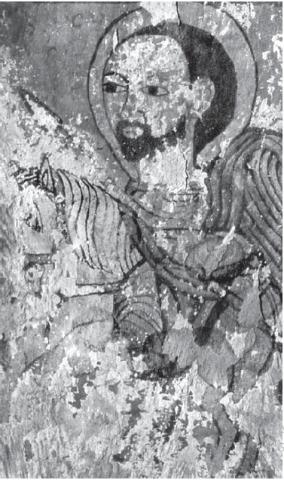

Emperor Yemrehana Krestos (~1090AD-1130AD)

After the reign of Ṭanṭāwedem, according to traditional accounts, Yemrehana Krestos (Guide Us/Have Mercy On Us Christ) ascended to the throne32. Yemrehanna Krestos was the son of Girma Seyon, who was the brother of Ṭanṭāwedem. According to tradition, much of his childhood was spent in hiding because Ṭanṭāwedem, having been informed by members of his royal court—referred to as “magicians” who could foresee the future—that his brother’s son, Yemrehanna Krestos, would eventually succeed him, so he grew wary and suspicious. The fear of being overthrown by an ambitious family member, a common occurrence in Abyssinian power struggles, prompted Ṭanṭāwedem to pursue Yemrehanna Krestos, who consequently fled south into Begemder, where he took refuge in caves and mountains33. It is highly likely that during his time in exile, Yemrehanna Krestos found refuge with monks, which fostered a deep connection to the Orthodox faith. After the death of his uncle, he journeyed to Lasta, where he garnered the support of the common folk, who accompanied him to the capital, Adfa. There, he was crowned as the next emperor. Yemrehanna Krestos remained deeply religious, instituting a law that banned all forms of witchcraft. His devotion to his faith was so profound that he was reputed to have performed priestly functions34. Moreover, he constructed a church, now known as Yemrehanna Krestos, located north of Lalibela.

The Life and Legacy of Yemrehanna Krestos: A Summary

The Gadla Yemrehanna Krestos is a hagiography, or a sacred biography, documenting the life and spiritual journey of Yemrehanna Krestos, a man in Ethiopian & Eritrean history who rose from humble beginnings to become a revered emperor and saint. The text is said to have been authored by a man named Zerubabel, who, during a visit to a church, received divine instruction from Yemrehanna Krestos himself, compelling him to document the narrated events.

The Gadla Yemrehanna Krestos (Life of Yemrehanna Krestos) was composed around the 15th century35, more than 300 years after the events it recounts, so it may contain inaccuracies. Additionally, the traditional narrative is religious in nature, with divine elements woven into the story. Despite this, we can still glean certain aspects of his life from it.

Early Prophecies

The narrative begins with Tantawedem, the reigning emperor of Ethiopia, who was warned by his royal courtiers of a prophecy. They foretold that a man named Yemrehanna Krestos would succeed him. Tantawedem was initially puzzled, as no one by that name was known at the time. However, it was soon discovered that his brother Girma Seyon had a son whose eyes emitted a miraculous light. When the child was just 40 days old, he was baptized and immediately spoke the words, “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Adam, Enoch, Noah, and Abraham, who dwells in the highest heaven.” This was seen as a divine sign, marking the child as someone of great significance.

Girma Seyon later had a vision where he saw his son becoming exceedingly wealthy and powerful. Hearing of these miraculous events, Tantawedem grew envious and fearful that his brother’s son might overshadow his own children, who were destined to become generals—a common fate for the brothers of emperors in Ethiopia. Influenced by jealousy and satanic whispers, Tantawedem considered killing the child but was persuaded by his courtiers to instead exile the boy and his mother to a distant land. This would prevent him from growing up in the royal court and learning the ways of kingship.

It is evident that Emperor Tantawedem was wary of his nephew. Throughout the history of Abyssinian Empires, power struggles between the sons and nephews of emperors were common. Typically, in Aksumite times, the emperor’s brothers served as generals.

Exile and Divine Protection

Yemrehanna Krestos and his mother were exiled, living a life of hardship far from the royal palace. However, the emperor later sent messengers to retrieve the boy under the pretence of love and affection. The mother, knowing the true intent was to kill her son, refused to comply and fled with Yemrehanna Krestos. She took him to a bishop, who ordained him as a deacon. From then on, Yemrehanna Krestos lived a life of wandering, moving from town to town, often hiding in the wilderness to escape those who sought his life.

During his time in exile, he married a woman named Qaddast Azba, who was from the Levant. He also became a priest, dedicating his life to baptizing pagans and spreading the Christian faith. One day, God appeared to him, reassuring him that he had not been forgotten. God promised that Yemrehanna Krestos would one day reign as emperor, and when he did, his name would be known as David. God further promised that the angel Raphael would protect him from his enemies.

It is likely that Yemrehanna was exiled and sought refuge far from the emperor’s reach. During this period, he was probably trained as a priest, which provided one of the few opportunities for him to interact with others, leading to his close association with the church.

Ascension to the Throne

Following God’s promise, Yemrehanna Krestos was guided by divine intervention and angelic protection. He returned to his homeland, where he performed various miracles, such as exorcising demons and resolving disputes among villagers. His reputation grew, and he was welcomed by the people, who saw him as a rightful ruler ordained by God.

As word spread that Emperor Tantawedem had died, the people of Ethiopia rallied around Yemrehanna Krestos. Riding a royal mule, he was taken to the royal court, where he was accepted as the new emperor. Upon ascending the throne, he introduced new laws that reflected his pious nature and commitment to Christian values. He outlawed polygamy, banned soothsayers who predicted the future, and emphasized the importance of brotherly love, mandating that brothers support one another, regardless of wealth.

During his life in exile as a priest, Yemrehanna likely formed strong connections with the common folk, including farmers and villagers, gaining a deep understanding of their struggles and daily experiences. This bond may explain why they supported his ascent to the throne following the death of his uncle.

Reign of Peace and Spiritual Leadership

Yemrehanna Krestos’s reign was marked by peace and religious devotion. Unlike other kings, he refused to take multiple wives and did not indulge in hunting or warfare. Instead, he focused on his priestly duties, much to the dismay of some members of the royal court, who preferred a more traditional, militant king. Distressed by their dissatisfaction, Yemrehanna Krestos sought divine guidance. God reassured him in a vision, instructing him to lead his people in faith and to build a church at a location that would be revealed to him during a hunt.

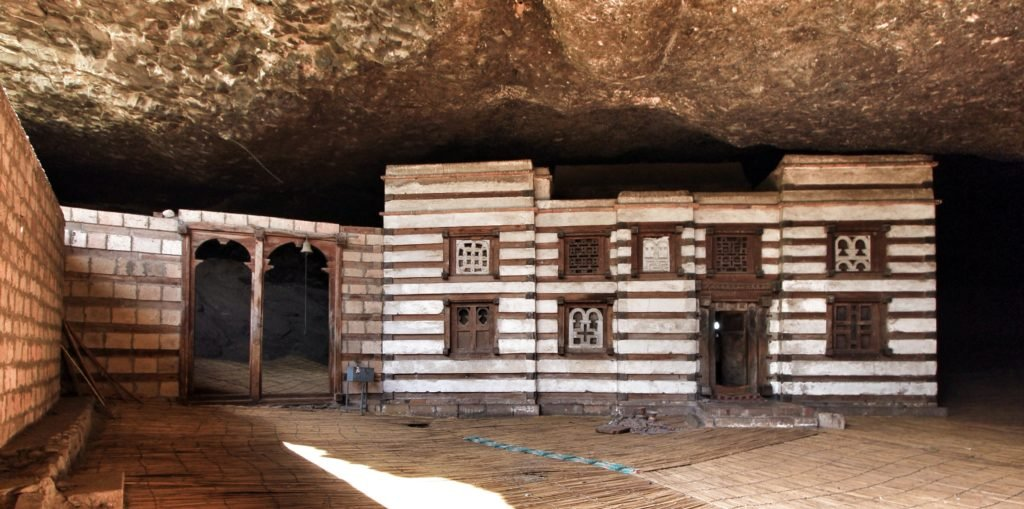

Obeying the divine command, Yemrehanna Krestos led a hunting expedition, during which he discovered a rock where the angel Raphael instructed him to build a church. This site, known as Wagra Sabin, later became known as the Yemrehanna Krestos Monastery, a significant religious landmark in Ethiopia.

Legacy and Death

Yemrehanna Krestos ruled for 40 years, a period marked by peace and the spread of Christianity. His fame reached as far as the Eastern Roman Empire, drawing bishops, priests, and deacons from various regions to visit him. Towards the end of his life, he led an expedition to Arabia to acquire gold and silver for his church. However, he fell ill during this journey. Despite his illness, he remained steadfast in his faith, crying out to God for strength. God reassured him once again, telling him not to fear. Yemrehanna Krestos died on the 19th of Tiqimit (29th of October). His soldiers mourned his passing deeply, placing his body in a coffin and bringing it back to Ethiopia, where he was buried in the church he had built.

The legend of Prester John originated in the early 12th century AD36, coinciding with the reign of Yemrehana Krestos. It is possible that Yemrehana Krestos’ efforts in promoting Christianity, building churches, and waging wars against Muslims spread across the world, even reaching Constantinople. It’s important to note that Abyssinians were not only present in Nubia or Alexandria in Egypt; they also visited Jerusalem during this period. Gadla Yemrehanna Krestos also claims the Patriarch Of The Orthodox Church at Alexandria came to visit during this period37.

A Portugese Perspective

According to Francisco Alvares, a 16th-century Portuguese explorer who travelled extensively across Abyssinia, the church of Yemrehanna Krestos was one of the remarkable sites he visited. He describes the church as being situated inside a vast cave, noting that “in my judgment, three large ships with their masts could fit within this cave”38. To reach the church, he had to ascend a mountain. Alvares described the church as impressively large, akin to a cathedral, with spacious aisles, intricate workmanship, and well-vaulted ceilings. It also contained three beautifully adorned chapels with elegant altars39. Additionally, he mentions a tomb believed to hold the remains of Yemrehanna Krestos and another for the Patriarch of Alexandria, who had died while visiting the site40. He also notes that the monastery at Gishen Debre Kerbe, also known as Amba Geshen in Wollo, Amhara, has been used to imprison the male relatives of the Emperor since the time of Yemrehanna Krestos41.

According to Gadl Yaemrehanna Krestos, he served as Emperor for 40 years42.

Gadla Yemrehanna Krestos has a great quote:

Sources

Bibliography

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 239 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 230 ↩︎

- The Zāgʷē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos, pg 159 ↩︎

- A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, pg 47 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation, pg 228 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 231 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 242 ↩︎

- https://tasbeha.org/hymn_library/view/2719 ↩︎

- https://st-takla.org/books/en/church/synaxarium/07-baramhat/03-paramhat-cosmas.html ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 241 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 242 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 249 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 242 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 241 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 42 ↩︎

- A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, pg 42 ↩︎

- The Zāgʷē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos, pg 163 ↩︎

- A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, pg 42 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 136 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 39 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 136 ↩︎

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, pg 639 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 139 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 140 ↩︎

- L’Enigme d’Une Dynastie Sainte Et Usurpatrice Dans Le Royaume Chretien d’Ethiopie, Xie-Xiiie Siecle (Hagiologia), pg 39 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 66 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 66 ↩︎

- https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-dahlak-islands-and-the-african ↩︎

- https://journals.openedition.org/aaa/2481 ↩︎

- https://journals.openedition.org/aaa/2481 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 67 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 249 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 250 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 250 ↩︎

- The Zāgʷē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos, pg 163 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 254 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 251 ↩︎

- The Prester John of the Indies, pg 202 ↩︎

- The Prester John of the Indies, pg 203 ↩︎

- The Prester John of the Indies, pg 203 ↩︎

- The Prester John of the Indies, pg 237 ↩︎

- Gadla Yemrehanna Krestos, pg 37 ↩︎