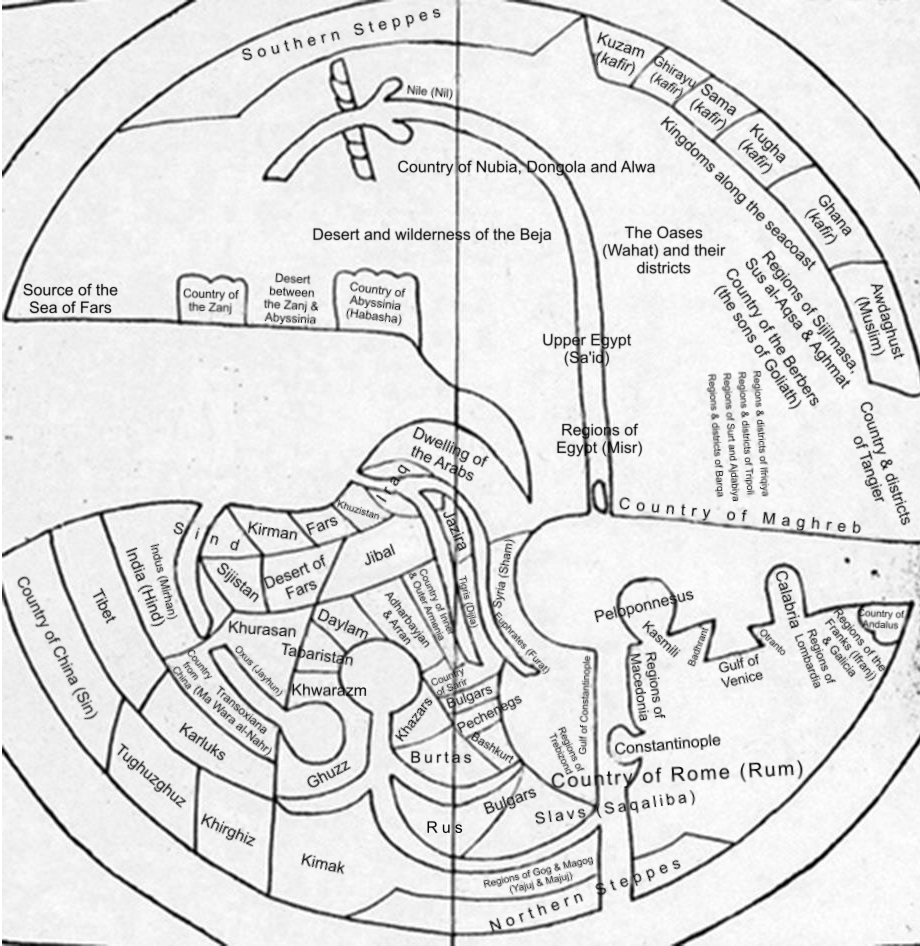

The North

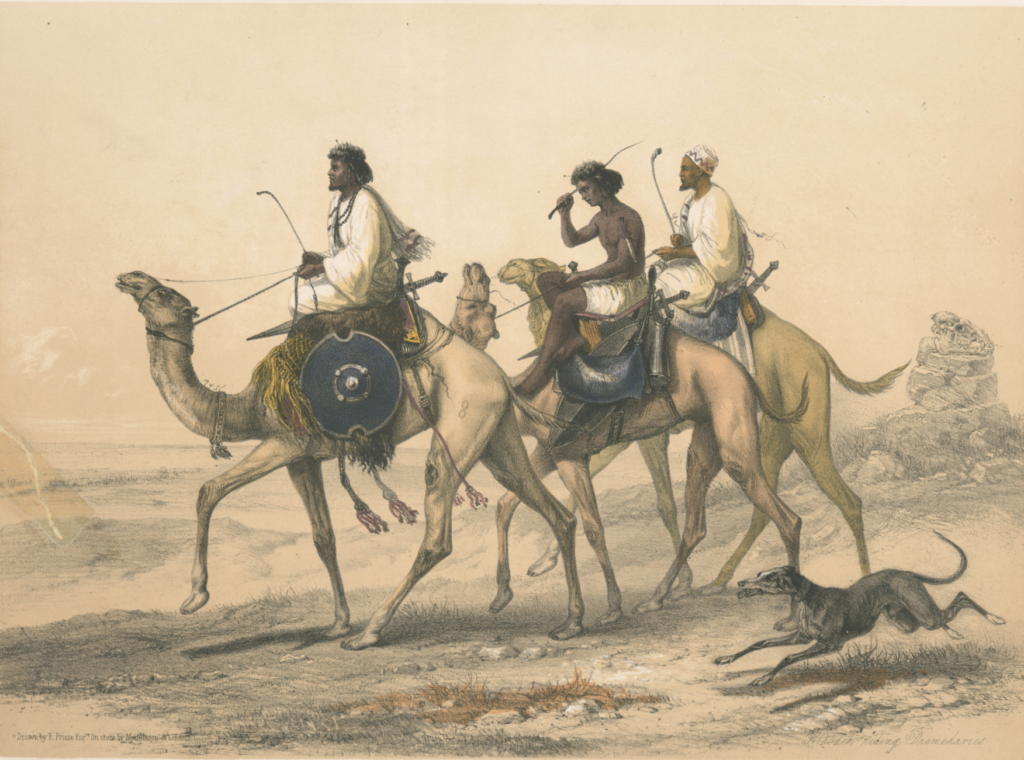

The Five Beja Kingdoms

In 831 AD, the Beja tribes in the north established a peace treaty with their long-time rivals in the west, the Kingdom of Alodia1. This allowed them to continue to focus on expanding further south into the northern periphery of the Aksumite Empire – The Eritrean plateau. As noted in the previous article, by the end of the 8th century AD, the Beja had already begun encroaching into the northern Aksumite heartlands, including modern-day Hamasien. By 872AD2, seven Beja kingdoms were established in North Eastern Africa, these stretched all the way from southern Aswan in Egypt to the Gash-Barka in Eritrea. The Arabian geographer Al-Yakúbi, in 872 AD, noted the following Beja Kingdoms 3:

- The Naqis Kingdom was occupied from the south of Aswan into the Barka Valley. Their capital was called Hajar, they were allies of the Muslims and this is where mines containing gold, emeralds etc were found4. They had seven tribes5:

- Hadareb – Modern-day Hedareb tribe, who live in northwestern Eritrea, near the Sudanese border. They were expert camel masters with camel-mounted spearmen6.

- Hijab

- Amaár – Called the Amarar tribe currently, and their territory is around northeastern Eritrea up to Saukin7.

- Kawbar

- Mansa

- Rasifa

- Arbarbá – Ababda Tribe that lives in northeastern Sudan, near the Red Sea8.

- Zanafj – Known as Dina Fana by Kebessa, They were originally a tribe with great authority9 however later on they became subservient to the Hadareb Tribe10.

- The Baqlin Kingdom inhabited the Sahil regions (Qarora region in modern-day Eritrea) down to the northern Barka-Valley11. Al’-Yakubi mentions that they worshipped a god named “Az-zabhir”, This is most likely referencing the term ègzi’abheer in Tigrinya which means God, they were likely Christianized Beja. Baqhla was the capital12.

- The Bazin Kingdom, located in the southwest (modern-day Gash-Barka Region in Eritrea), was home to the Kunama and Nara peoples13. They were also at war with the Baqlin Kingdom in the north14. They practised agriculture and were governed by a council of elders15.

- The Jarin Kingdom stretches from Badi (Massawa) to Hall Ad-dujaj meaning Fowl Market/ Fowl mountain (Tigrinya name is Emba Derho16). They extracted their upper and lower teeth and shaved their beards in arc/bow styles17.

- The Qata Kingdom, Around the west of Badi to a place called Faykun (Location unknown). They were great warriors and had military academies18.

Two other kingdoms were listed by Al-Yakubi, although these weren’t Beja they’re important and need to be addressed:

- The Kingdom of The Najashi, references that the kingdom was large & the capital was called Ku’bar & the port was near the Dahlak Islands (Adulis). This is important as it reveals that the Aksumite Empire was still around in 872AD, of course in a greatly reduced form, in addition to this it still had control of Adulis & the Dahlak Islands (which were captured temporarily in the 8th century AD).

- The Zanj: Scholars are unsure as to who this is referencing, but it’s a land to the southeast of Ethiopia19.

Around 872AD, Most of the Beja kingdoms were Pagan however the southernmost peripheries were likely Christianized & a tributary state of the Aksumites20.

The Direct Quote Of Al-Yakubi is as follows:

The Dahlak Islands

The Dahlak Islands, as previously mentioned, were seized by the Umayyad Caliphate in the 8th century and transformed into a prison for notorious criminals and exiles21. However, by the 9th century AD, the islands briefly returned to Abyssinian control. Authority shifted again in the late 9th or early 10th century when the Yemeni Ziyadid dynasty occupied them22. Despite these changes in control, the islands consistently served as a crucial gateway for Muslim traders, facilitating the spread of Islam along the Eritrean coast.

In the 11th century, the Dhalak Sultanate emerged24, however, the polities of the 11th century will be covered in the Zagwe Kingdom articles…

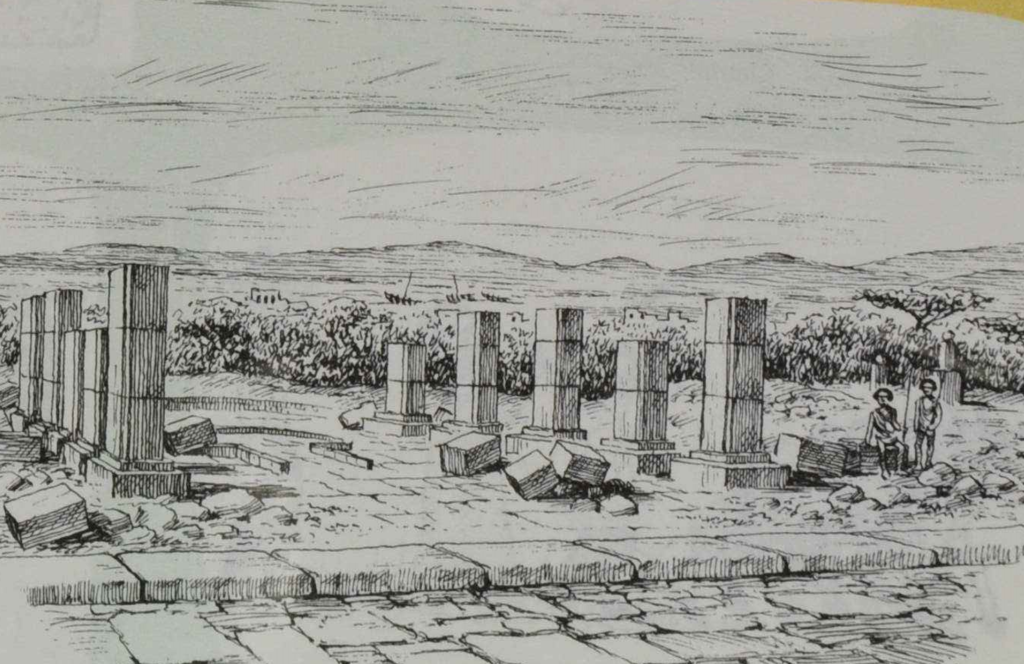

Adulis

As discussed in the previous article, Adulis faced an attempted invasion in the early 8th century AD, which, though successfully repelled, resulted in the city’s sacking. This likely diminished its naval capacity, a situation exacerbated by the capture of the Dahlak Islands throughout the century, further restricting naval operations from the port city. Additionally, Massawa, located further north, had become the primary port for Arab merchants, diverting much of the maritime trade away from Adulis.

However, these military and economic challenges alone did not lead to the demise of Adulis. It was likely a series of natural disasters that sealed the city’s fate. Some scholars attribute the destruction to an earthquake, others to a flood, and still others to a major fire25. While we cannot yet confirm which disaster was responsible, the flood theory remains the most widely accepted. By the late 10th century AD, mentions of Adulis were long gone, and arab geographers of this period no longer mentioned Adulis, rather they mentioned Badi & Zeila as the ports for Absynnians26.

The Aksumite Coup – General Hasani Daniel (7th – 9th AD)

The exact period when the events of the Hasani Daniel occurred is speculated by scholars, some pin it to as early as the 7th century AD such as Munro-Hay27, however, most scholars are unable to pin a date, with a date until the early 10th century AD possible28.

I’ve chosen the period between the late 8th and mid-9th century AD, as the mention of Ku’bar as the Aksumite capital by Arabian historians by 872 AD precludes any date later than this. Additionally, an earlier date, prior to the late 8th century AD, seems improbable, because as noted in a previous article, a major expedition was launched in 748 AD with Nubian assistance, which would have been highly unlikely during a time of civil conflict.

During the continued expansion of the Beja kingdoms in the north, which included the sacking of Adulis and the occupation of the Dahlak Islands in the early 8th century AD, the Aksumite Empire faced mounting economic strain. This turmoil inevitably led to a significant rebellion that reshaped the Aksumite political landscape. As a result, the traditional title of “Negus” for the emperor was replaced with “Hasani,” and the capital was relocated further south. The man who led this rebellion was a general named Hasani Daniel, son of Dabra Ferem.

Interestingly no mention of these two figures (Hasani Daniel or Dabra Ferem) exists in traditional monarch lists, possibly alluding to the purposeful erosion of their name.

General Hasani Daniel, an Aksumite military leader29, launched a successful campaign against the Beja kingdoms, focusing primarily on the Bazen Kingdom. His forces advanced as far as Kassala, seizing livestock and taking captives as spoils of war, during these battles he came across another “hatsani” named Karuay and defeated him.

In another inscription, Hasani Daniel recounts a defensive campaign against the Wolqayt people, who had attacked a location referred to as HSL (the exact location remains unknown) before advancing on Aksum itself. The Wolqayt were decisively defeated, with livestock and captives taken. The Wolqayt, reached as far as Aksum, suggesting a significant increase in their power during this period. These two inscriptions are as follows:

In the final inscription, Hasani Daniel describes his overthrow of the Aksumite Emperor in Aksum. He suggests that a negotiated settlement was reached without any direct combat between the armies, resulting in the Emperor becoming a tributary ruler under his authority. These inscriptions paint a picture of a turbulent era marked by civil wars and weakening central authority in Aksum. It is highly probable that during Hasani Daniel’s time, the Aksumite capital began shifting from their administrative capital from Aksum to Ku’bar. The inscription is as follows:

Hasani may be derived from the word asena meaning King in Agaw30. Atse (ዐፄ) would later mean Emperor during the Zagwe & Solomonic Era31. Hasani Daniel could be the origin point of the change in this word’s meaning from King to Emperor.

Interestingly only the Zagwe kings used the term Hasani (in this strict form). It fell out of use after 1225 and was rather used to define a provincial ruler during the reign of Amda Seyon32.

Hasani Daniel’s rebellion might be viewed as marking the fall of the Aksumite Empire. However, this is debatable; the local population likely did not perceive it as the beginning of a new dynasty, and indigenous manuscripts from this period do not indicate the start of the Zagwe era at this time, rather they attribute it to the fall of Dil Na’od by Mera Tekle Haimanot (as discussed in the final section).

The Southern Expansion (Late 7th, 8th and 9th Centuries)

Contrary to the events unfolding in the northern peripheries of the Aksumite Empire during the 8th and 9th centuries, Aksumite forces were actively expanding their territory in the south during this time. Historian Taddesse Tamrat explains that establishing military colonies was the standard practice in these newly conquered southern regions33. He theorizes that the Amhara tribe was among the earliest communities to be Semitized during an early Aksumite period, predating the arrival of Christianity and, therefore before the reign of Emperor Ezana34 (It is documented that Emperor Ezana travelled southwards to conquer the Afan, who were believed to inhabit the extreme southern regions, so this theory does hold weight). Taddesse also notes that by the early 9th century AD, a Semitized Amhara population had already been established around the Bashilo River (in Wollo) and extended southward to the Jamma River (in North Shewa)35. Later, kings such as Dagna Jan, Ambessa Wudem, and Dil Na’od would commemorate their southern conquests by building churches in these regions.

In the 9th century, the Absynnians had penetrated as far as Zeila in the south-east & into the central Shewa36, however, Zeila and it’s surrounding territories are known as Adal by arabic sources37, therefore it was likely Zeila and Adal were in a tributary relationship with the Aksumites. In Southern Shewa, the Mahzumite dynasty is said to have been established38. It was originally from an Arab clan from Mecca39. During this time they were a tributary state of the Absynnian Kingdom40.

Emperor Dagnajan

We know of a ruler named DagnaJan in the early 9th century AD (825-845, According to Sergew Hable Selassie’s regnal list41) , I’m theorizing a time frame around 845-875AD, taking into consideration “The life of Patriarch Joseph (830-849)” which is explained later on in this section. According to manuscripts found by Qese Gebrez Tekel Haimont of Aksum and Translated by Sergew Hable Selassie42, DagnaJan amassed an army of over 100,000 soldiers who marched westward toward the land of the Arabs. However, his campaign ended in failure, as he reportedly died after being unable to cross the land.

The inscription goes as follows:

Sergew Hable Selassie suggests that “The Land of the Arabs” was likely located in the southwest of Aksum, near Damot43. He based this conclusion on the analysis of the word “Arab” mentioned as a neighbouring province next to Damot in the chronicles of Amda Seyon44. This region might also have been referenced by Cosmas as the land of Sasu, known for its gold. It is highly probable that by the 9th century AD, Damot had already emerged as a powerful kingdom exerting significant influence in the south, and it was beginning to encroach on the weakened Abyssinian kingdom in the north. The Damot kingdom consisted mainly of Woloyta & Sidama peoples.

Historian Sergew Hable Selassie notes another account of this ruler in a different manuscript, which mentions that he moved his capital from Aksum to Weyna Dega (in Gondar/Begemidir45). Accompanied by 150 priests, and an army they travelled further south, crossing the Semien Mountains, passing through Gondar, and continuing beyond Lake Tana. After this, the sequence of events described appears somewhat disjointed and may refer to the period of Ambessa Wudem. During this time, Dil Ne’ad, his son, was leading an army of 18,500 soldiers and met with his father, who may have been terminally ill, thereby leaving the kingdom to his son. The text then indicates that after the reign of Dil Ne’ad, the kingdom was no longer ruled by the Israelites—likely a reference not to Gudit—but rather by the Zagwe dynasty, who were of Agaw origin.

Historian Taddese Tamarat points out that the 13th-century monk & saint Tekle-Haymanot had referenced that his ancestors had settled in Shewa ten generations before, during the reign of DagnaJan46, thereby alluding to the fact of southern expansion during DagnaJan’s reign. Interestingly Taddese points out that the manuscript “Gedle Iyesus-Mo’a” states the date of creation for Istifanos Monastery was around 870AD47 – around the time of DagnaJan.

The inscription goes as follows:

Sergew Hable Selassie notes the following locations48:

Fiq – East of Gondar.

Dergina – Unidentifiable but somewhere in the Gondar area.

Tahya – In Semien Mountains

Rib – Reb river, near Laka tana.

The life of Patriarch Joseph (830-849)

The historical document “History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria” offers a fascinating account concerning the Abyssinian king during the time of Patriarch Joseph (830-849 AD) – likely referring to DegnaJan. It notes that the Abyssinian king was engaged in warfare, which aligns with information previously gathered from traditional manuscripts. The document also describes a liturgical dispute that arose during the king’s absence, leading to the removal of a bishop who had been appointed by the Egyptian patriarch in Alexandria. This removal reportedly resulted in significant misfortune for the kingdom, including a devastating plague that claimed the lives of many people and livestock, as well as a severe drought.

The text further mentions that the Abyssinian king suffered multiple defeats—paralleling what we know about DagnaJan’s defeats in his wars—and suggests that his successor, likely Ambessa Wudem, also faced similar losses. Interestingly, it alludes to the involvement of a queen behind these events. While this could be interpreted as a reference to Gudit, her rebellion occurred 50-100 years after Patriarch Joseph’s lifetime, suggesting that the timeline might have been confused by the authors of the “History of the Patriarchs.” Eventually, the document states that a bishop was sent after the Abyssinian king sent a letter apologizing for the earlier incident.

A gap of approximately 50 years exists between the end of DegnaJan’s reign and the rise of Gudit, in my chronology of the events that occurred. This can be attributed to several factors: 1) the general imprecision in dating events from this period, which could result in discrepancies of a few decades; 2) the likely dissolution of central authority, leading to multiple kings ruling over the Abyssinian Empire simultaneously; 3) the Falasha rebellions, which culminated in the establishment of their own kingdom in the late 9th century AD. Additionally, Eldad Ha-Dan’s mention of “five Ethiopian kings” likely refers to this turbulent period, when various rulers were vying for power.

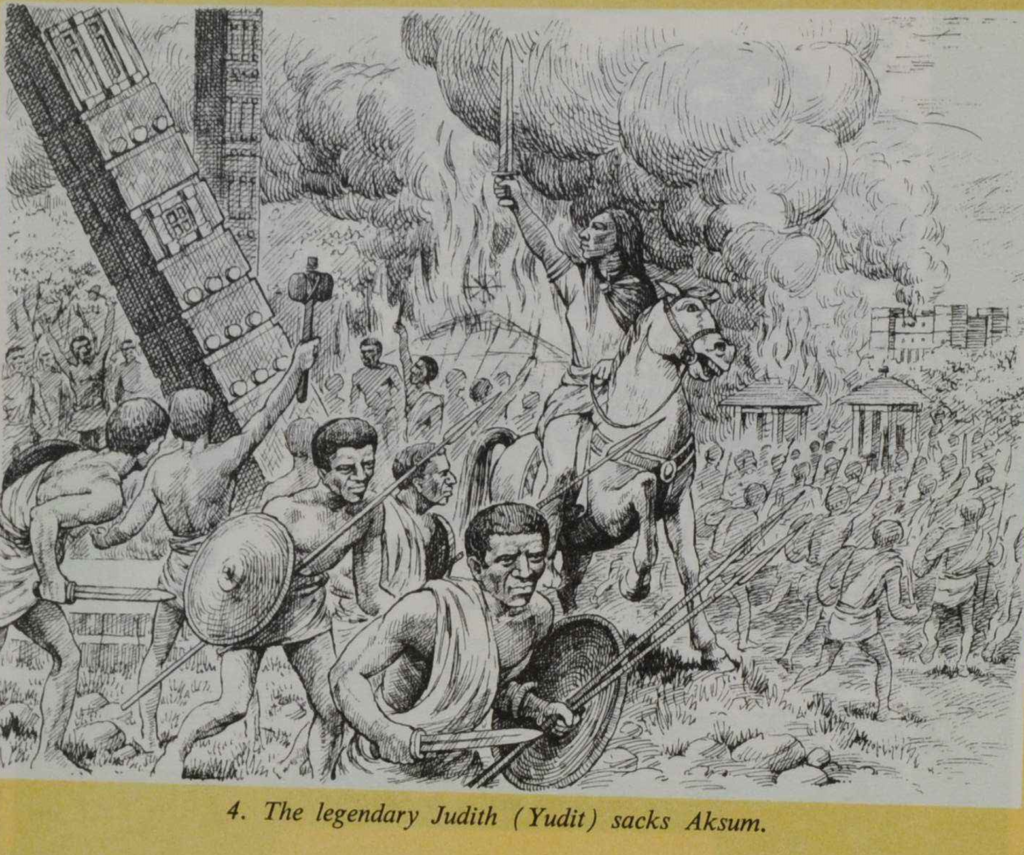

Gudits rebellion (~920AD)

The Falasha Rebellions

Around the early 9th century AD, a significant rebellion was led by a woman named Gudit, whose story is recounted in various traditional texts. There are multiple accounts and sources pointing to a Falasha rebellion, with the most famous being the stories of Gudit. I, we will first examine this rebellion through the perspective of a Falasha explorer and merchant named Eldad Ha-Dani, in the late 9th century AD49. Then two inscription describing the reign of Gudit will be analyzed.

Eldad Ha-Dan claimed to be from an independent Jewish kingdom known as “The Dan”, located in east africa and stated that his people were in constant warfare with five neighbouring Ethiopian kings. Historian Sergew Hable Selassie suggests that Eldad was likely a Falasha himself50. By analyzing his claims and the timing of these texts, we can infer that the Falashas, who lived near the Semien Mountains, enjoyed a form of independence, no longer subjected to the Habeshas by the late 9th century AD. Eldad’s mention of five different Ethiopian kings hints at a period of significant internal strife, reminiscent of the Zemene Mesafint, which would unfold a thousand years later. It is unsurprising, then, that the Falashas had achieved independence during this turbulent time, and then would likely assist in Gudits rebellion.

Inscription 1

Historian Sergew Hable Selassie translated an excerpt from a traditional manuscript (Provided by Qese Gebez Teke Haimanot of Aksum) that provides some background on Gudit. It is said that she originated from the land of Sham, likely referring Kingdom Of Dam (Semien Mountains area – Falashas) rather than Bilad al-Sham province of the Umayyad Caliphate, which encompassed parts of modern-day Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria51. Gudit reportedly arrived with a man named Zenobis at Dihono (Arkiko52, about 10km south of Massawa in Eritrea). She then informed her homeland (referred to as Hahayle, a place in Adwa53), saying, “I have gathered many soldiers and come here. Join me soon, or you will be my enemy.” Some people deserted and joined her at Asaorta (a Saho clan name in southern Eritrea, Akele Guzai54). She then advanced her forces to Shilinuqwu (location unknown but likely closer to Aksum). The text states that she created a road from Massawa to Aksum for her troops, and no one could stop her. Gudit then entered Aksum, and destroyed the palace, the church built by Ezana and Saizana, the stelae, and the wells. She declared that churches should be closed, as she and her husband, the new rulers, were Jewish. Priests were persecuted, and the Ark of the Covenant was taken east to Zuway (Debre Tsion Mariam Monastery, located on an island in Lake Tana55). Gudit is said to have ruled for forty years before dying. She was succeeded by Anbessa Wudem, who brought peace and ended the persecution of Christians, allowing the Ark of the Covenant to return.

The inscription goes as follows:

Analysis

What can we infer from this? Firstly, the claims of Gudit’s Jewish descent seem unlikely, rather she had gathered support from the Falashas who were from the Land of Sham (Kingdom Of Dan) , who had a prince named Zenobis. Secondly, she had royal lineage, being the granddaughter of Emperor Wuden Asfere, who, according to royal records, reigned from 792-822 AD. Her mother’s country, Hahayle, is mentioned, which appears to be a location in Adwa. This suggests that she wasn’t entirely a foreigner, but possibly of mixed Falasha heritage. She also likely secured military assistance or a pact from a foreign power with a Jewish affiliation (most likely the independent falasha kingdom mentioned earlier).

Thirdly, her headquarters were likely based around Arkiko, near Massawa, an area that had been under Arabian/Beja influence for centuries and was beyond Aksumite’s control. Gudit initiated her rebellion by issuing a warning to anyone who opposed her and seemingly garnered support from within the empire (this alludes to dessent already existing within the aksumites). She then advanced her troops from Massawa up the Eritrean plateau, encountering little resistance as she entered Aksum (this makes sense, as we seen before Emperor DegnaJan had apparently amassed 100,000 troops & pushed south into the Damot area, & had been defeated/lost, therefore much of the Imperial army wasn’t at Aksum to defend it from Gudit) .

While she was near Massawa (which was under the control of the Jarin Kingdom, as discussed earlier), she likely acquired the support of Beja tribes, who were already at war with the Aksumites in their northern territories.

It is evident that significant destruction occurred during this period, likely including the defacement of Aksumite thrones, tombs, and possibly the toppling of one of the stelae. It is also suggested that she sabotaged wells, leading to starvation among the local population in Aksum (the analysis of Patriarch Joseph’s life earlier alludes to a famine as well…). Furthermore, the persecution of christians was so severe that the Ark of the Covenant was moved from the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Tigray to an island in Lake Tana, indicating that the region around Lake Tana was likely outside of Gudit’s control, or at least, she had minimal influence there.

Finally, it is understood that Gudit ruled for 40 years. She was then succeeded by Anbessa Wudem, who restored order and re-established Christian rule.

Inscription 2

Sergew Hable Selassie then mentions the existence of another manuscript he translated from Qese Gebez Tekel Haimantot that goes into the backstory on why Gudit started the rebellion, it is as follows:

Analysis

Firstly, it’s evident that Gudit experienced a significant fall from grace, becoming impoverished despite her royal lineage. This suggests she or her parents may have committed some transgression that led to her downfall. Desperation pushed her into prostitution, which was particularly scandalous given her noble background.

When a young priest sought to engage with her, Gudit rejected his advances unless he could provide her with a gold veil and golden shoes. The priest, leveraging his access as a clergy member, stole a piece of the golden curtain from the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion to fulfill her demands. However, the missing piece was soon noticed, and suspicion fell on Gudit. When confronted, she admitted to possessing the golden shoes but claimed ignorance about their origin, only revealing that a young man had given them to her.

The elders and judges, however, placed the blame solely on Gudit, accusing her of manipulating the young priest into committing the sacrilegious act. As punishment, they mutilated her by cutting off her right breast and exiled her from the country to the Red Sea, likely near Arkiko.

These events are highly questionable; it’s unlikely she manipulated a priest to commit theft. However, she was probably punished for a serious crime, likely connected to the royal court. This would align with the idea that Gudit was enraged by the decline of her royal lineage. She was most likely exiled to the northern red sea, as this lines up with the previous manuscript.

While in exile, Gudit encountered the son of the King of Sham (this is probably the kingdom of Dam referenced earlier, therefore the Falashas had aided her) , possibly a prince visiting Massawa. Sympathetic to her plight and her mutilation, he married her. Gudit then renounced Christianity, adopting Judaism, her husband’s faith. Fueled by a desire for revenge against the Aksumite rulers, she persuaded her husband to gather his army to help her overthrow them. Initially, he hesitated, fearing the power of the Aksumite Emperor Dagnajan. However, after receiving intelligence that Dagnajan had suffered a defeat during a military expedition in a distant land (again this lines up with the inscription of him venturing far south), Gudit urged her husband once again to attack, sensing an opportunity to strike while the empire was vulnerable.

An Arabic Perspective On The Rebellion

The 10th-century Arabic geographer and historian Ibn Hawqal documented that during this period, a Queen was ruling Abyssinia, using the title “Hadani,” which is probably derived from “Hasani.” This suggests that she was associating herself with the lineage or ideology propagated by Hasani Daniel, rather than the Aksumites. The historian further notes that she not only dominated Abyssinia but also exerted control over the neighbouring region to the west, identified as the land of the Hadani (Italian Colonial Histroain, Conti Rossini, suggests that this region corresponds to Damot). If she had control of Damot, then it’s very likely Damot had assisted her with ruling the Aksumites, like we mentioned before DagnaJan likely led the expedition into Damot, therefore it’s within reason that after his defeat they had pushed further northwards.

The inscription is as follows:

Finding A Date For Gudits Rebellion

Ibn Hawqal travelled between 943 and 977 AD56, completing his book in 978 AD57. Therefore, the events he described occurred within this time frame. He journeyed from Baghdad to South Arabia around 947-951 AD58, which is likely when he either witnessed or heard about the events in Abyssinia. His mention of these events spanning “many years” suggests that he was not referring to the beginning of Gudit’s reign when he was there at around 950 AD, but rather that at least a decade had likely passed. Using this information, we can estimate the timeframe of Gudit’s rebellion and rule to be approximately between 920 and 960 AD.

The margin of error is likely 10-30 years…

A Timeline Of Events

Around 930AD, there was a woman named, Gudit. She was likely a woman of mixed heritage, with Sidama origins on her father’s side and Aksumite royal lineage on her mother’s side, tracing back to her grandfather, Emperor Wuden Asfere. However, by the time of her parents’ generation, her family had lost their noble status, leaving her in destitution. This likely fueled her anger, leading to her committing a crime severe enough to warrant punishment and exile to the north, near Massawa.

While in Massawa, she encountered a prince from the Kingdom of Sham, who was likely there for commercial reasons, given the port’s bustling activity at the time. They had an affair, married, and she converted to Judaism. With her ambitions set on avenging her family’s fall from grace, she began to recruit support. She gained allies among the Beja tribes in Massawa, utilized her husband’s connections, leveraged her family’s former royal ties, and possibly drew on her father’s influence in the southern Damot territories.

When she learned of Emperor DegnaJans’ death in Damot and the decimation of his army far to the south, she saw her opportunity. She planned a coordinated attack: her husband’s forces would strike from the Semien region, while she, supported by Beja tribesmen and Aksumite dissenters, would attack from the north, with the Damot kingdom pushing from the south.

Gudit then marched towards Aksum, passing through Akele Guzay before finally entering the city with little resistance. Once in Aksum, she exacted her revenge on the royal court and clergy. She likely ruled for about 30 years, and after her death around 960AD and the chaos she unleashed, the rightful heir, Ambessa Wedem, reclaimed the throne with his forces.

Some scholars claim Gudet is of Sidama origin, this is probably partially true. Both Taddesse & Sergew cite that south-western Ethiopia, near Damot there were traditions of Queens who waged wars with the Christian Abyssinians59.

Ambessa Wudem (960-980AD)

Finally, after the death of Gudit, around ~960AD, Ambessa Wudem ruled, he ruled for twenty years, ten as an emperor in exile (during the reign of Gudit) and then 20 years as Emperor60. In the previously mentioned manuscript collected from Qese Gebez Tekele Haimanot, it attests to his rule in exile during the reign of Gudit, by hiding in the mountains (of which there is many in the highlands..). The excerpt is as follows:

During Ambessa Wudems reign he had restored control of areas in the north in Eritrea, in addition to reinstating christianity as the state religion and building churches, we can gather this information from an excerpt from a manuscript translated by Sergew Hable Selassie:

The Monastery of El Arebeh on the Red Sea coast, could be a reference to Debre Sina in Eritrea, which was founded by Abreha (Emperor Ezana).

In the south, Wudem expanded the spread of Christianity near Lake Haik (Wollo) and Shewa by permitting priests to proselytize in these regions and overseeing the construction of churches61.

The Last Aksumite Emperor Dil Na’od (980AD-990AD)

After the death of Ambessa Wudem around 980AD, his son Dil Na’od ruled, he would become the last Aksumite Emperor. He rebuilt churches such as the the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion which was broken by Queen Gudit and built new ones such as Michael Amba, in Tigray62 . From the previous mentioned “Chronicle Of Ethiopia” manuscript that Sergew Hable Selassie translated we can glean as to what occurred that led to the death of Dil Na’od and the transition to the Zagwe empire.

“Chronicle Of Ethiopia”

The accuracy of the whole story is obviously not completely certifiable, however, we can understand certain dynamics that occurred during his reign by analyzing the excerpt from the manuscript.

From this manuscript, we can discern the following: The Emperor sought to survey regions further to the southeast, southwest, and west, likely to expand his empire and secure a strategic position to prevent invasions from the Kingdom of Damot and other adversaries in the area. Specifically, he dispatched surveyors towards Shewa, Enarya (near Damot), and Sennar (in Sudan). However, only one surveyor returned with positive news. Despite the successful journey, a dispute arose between the surveyor and the Emperor over who deserved credit for the success—the surveyor attributed it to divine intervention, while the Emperor claimed it as his own. This disagreement escalated, resulting in the surveyor’s imprisonment.

It’s likely during Dil Na’od’s reign that he continued his predecessor’s missions of expanding territory in the south, so this opening paragraph comes to no surprise. The dispute between the Emperor might allude to his temperament during his reign.

A monk, upon hearing of this, accused the Emperor of blasphemy and prophesied that in the future, the Emperor’s daughter would rule in his place. Troubled by this prophecy, the Emperor decided to abandon his three-month-old daughter in a ditch. Days later, a servant discovered the child while hunting, naming her Mesobe Werq (meaning “basket of gold”) after finding her in a basket. When the Emperor inquired about the servant’s hunt, the servant mentioned the girl, leading the Emperor to recognise her as his daughter. To ensure the servant’s silence, the Emperor entrusted him with the care of Mesobe Werq and appointed him as the master of Mera Tekle Haimanot, giving him control over a quarter of the last province.

This set of events is questionable, it’s more likely that she wasn’t abandoned by her father, which is what the second manuscript states..

As Mesobe Werq grew up, she had a confrontation with Mera Tekle Haimanot, who wished to marry her. This was against the law, as she believed he was her father. Mera Tekle Haimanot then revealed to her that her true father was Emperor Dil Na’od, and that she was named Mesobe Weqe because she had been found in a basket in a ditch. Upon hearing this, she wept, but an angel appeared and comforted her, saying that she and her descendants would inherit a new kingdom. Encouraged by this vision, she told her husband that God would be with them and advised him not to rebel against the king.

When the Emperor later summoned Mera Tekle Haimanot to pay tribute, he repeatedly refused, citing illness. After several failed attempts, the Emperor sent a military expedition to capture him, but Mera Tekle Haimanot’s forces defeated them. The Emperor then led another army personally, but they too were defeated, and he was forced to retreat. In the final battle, the Emperor was pursued by Mera Tekle Haimanot and his army. Ultimately, the Emperor was struck by a spear in the back. When questioned about who had pierced him, the Emperor’s final words were, “The one who pursued me pierced my back.” This gave rise to the name “Zagwe” for the new dynasty, as “Zagwe” means “the one who pursued the king.”

This final paragraph most likely did occur, his Tekele Haimanot’s refusal to pay tribute to the Emperor, led to retilation and the defeat of the Emperor. He might have then tried to escape, however he was caught out by Tekele’s forces. It’s then claimed the origin of the term Zagwe comes from the ge’ez word, ዘአጒየየ (zaagwayaya) which means “he who runned” or in this context “he who pursued”63

Analysis Of Gedle Iyasus Excerpt

Gedle Iyasus provides a slightly different version of events64, where Emperor Dil Na’od had a daughter named Mesobe Werq. The royal council and priests had decreed that whoever married the daughter would inherit the kingdom. To prevent this, the Emperor imprisoned her in the royal palace. However, a nobleman from Lasta, named Mera Tekle Haimanot, became a close friend of the Emperor. Their friendship grew so strong that Mera Tekle Haimanot was granted access to Mesobe Werq’s chambers, where they eventually fell in love. Mesobe Werq expressed her desire to marry him to her father.

At this time, the Emperor was suffering from a debilitating disease that caused him to scratch his skin and seek warmth near a fire. Mesobe Werq informed Mera Tekle Haimanot of her father’s condition, and one day, Mera Tekle Haimanot visited the Emperor. In an attempt to win his favour, he helped relieve the Emperor’s pain by scratching his skin and, during this act, asked for his daughter’s hand in marriage. The Emperor, in his weakened state, agreed.

However, when the Emperor regained his senses the next day, he no longer approved of the marriage and demanded that Mesobe Werq be returned. Nonetheless, he insisted that the marriage ceremony take place first. Mera Tekle Haimanot, suspecting that the Emperor intended to keep Mesobe Werq imprisoned indefinitely, refused to return her. When the Emperor sent his army to retrieve her, they were unsuccessful, and Mera Tekle Haimanot ultimately became the new Emperor.

My Analysis

From analyzing both manuscripts we can come to a conclusion as to what events probably happened that led to the creation of the Zagwe Kingdom.

Emperor Dil Na’od and his royal courtiers, many of whom were likely priests, were well aware of the power and influence of Mera Tekle Haimanot, a provincial king or prince from Lasta, probably of Agaw origin. Tekle Haimanot possessed considerable land and commanded a powerful army. The court foresaw that one of the ways he could seize power without resorting to force would be through marriage to the Emperor’s daughter, particularly since Dil Na’od likely had no sons. Concerned about this possibility, Dil Na’od likely tried to keep his daughter hidden from Tekle Haimanot. However, Tekle Haimanot eventually succeeded in courting the Emperor’s daughter, who may have resented her father’s attempts to keep her isolated, further straining relations between Tekle Haimanot and Emperor Dil Na’od.

This tension eventually led the provincial Agaw king to cease paying tribute to the Emperor, sparking outright military hostilities that Dil Na’od promptly lost. After his defeat, Dil Na’od might have attempted to flee but was ultimately captured by Tekle Haimanot’s forces, giving rise to the rumours and legends surrounding the new emperor and the civil war he had won.

Bibliography

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 207 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 207 ↩︎

- https://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Al-Ya%27qubi ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 49 ↩︎

- A History of the Beja Tribes of the Sudan, pg 20 ↩︎

- https://www.101lasttribes.com/tribes/hedareb.html ↩︎

- https://www.sudanmemory.org/image/SNR-0000521/24/ ↩︎

- https://fanack.com/egypt/population-of-egypt/the-ababda-tribe-nomads-between-egypt-and-sudan/ ↩︎

- https://www.samadit.com/index.php/en/documents/language-ethnicity/4321-a-brief-sketch-of-the-bejas-of-eritrea ↩︎

- A history of the Beja Tribes of the Sudan 69 ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 49 ↩︎

- https://www.samadit.com/index.php/en/documents/language-ethnicity/4321-a-brief-sketch-of-the-bejas-of-eritrea ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 207 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 207 ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 51 ↩︎

- The Dynamics of an Unfinished African Dream: Eritrea: Ancient History to 1969, pg 54 ↩︎

- https://www.samadit.com/index.php/en/documents/language-ethnicity/4321-a-brief-sketch-of-the-bejas-of-eritrea ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 50 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 222 ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 50 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 65 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 66 ↩︎

- The Cambridge History of Africa (1050-1600), pg 119 ↩︎

- The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia, pg 66 ↩︎

- The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis, pg 119 ↩︎

- The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis, pg 121 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilization Of Late Antiquity, pg 262. ↩︎

- History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia, pg 276 ↩︎

- Layers Of Time: A History Of Ethiopia, pg 46 ↩︎

- Layers Of Time: A History Of Ethiopia, pg 46 ↩︎

- Layers Of Time: A History Of Ethiopia, pg 46 ↩︎

- A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, pg 38 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 71 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 72 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 73 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 73 ↩︎

- Peoples of the Horn of Africa : Somali, Afar and Saho, pg 140 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 99 ↩︎

- Medieval Islamic Civilization, pg 12 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 99 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 203 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 230 & 231 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 230 ↩︎

- The Glorious Victories Of Amda Seyon, pg 1 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 231 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 68 ↩︎

- Church and State in Ethiopia 1270 – 1527, pg 69 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 231 ↩︎

- https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5515-eldad-ben-mahli-ha-dani ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 213 ↩︎

- https://referenceworks.brill.com/display/entries/EIEO/COM-1031.xml?rskey=kNmLD6&result=1 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 227 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 227 ↩︎

- https://en.sewasew.com/p/asaorta-(%E1%8A%A0%E1%88%B3%E1%8B%8D%E1%88%AD%E1%89%B3) ↩︎

- https://actiontourethiopia.com/debre-tsion-mariam-monastery/#:~:text=Debre%20Tsion%20Mariam%20Monastery%20(Tullu%20Gudo)%20of%20Lake%20Zeway%20is,from%20the%20town%20of%20Zeway.&text=Lake%20Zeway%20is%20also%20a,Tree%20hyrax%20and%20hippopotamus ↩︎

- https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/ibn-havkal ↩︎

- Islam In Ethiopia, pg 52 ↩︎

- https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/ibn-havkal ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 230 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 233 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 232 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 233 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 236 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History, pg 236 ↩︎