In this period, the Aksumite Empire faced rebellions, resulting in a territorial decline. However, it endured, welcomed numerous saints from the Roman Empire, and launched an invasion of Himyar.

Introduction

After the death of the twin emperors, Ezana and Saizana at around 360 AD, the Aksumite Empire experienced territorial contraction, with successful rebellions on its periphery. Compared to the preceding and succeeding eras, the 5th century AD is poorly documented, particularly in terms of primary indigenous sources. As a result, we have to rely on Roman accounts and numismatic evidence from the coinage minted during this period to reconstruct events.

This gap is partly due to the current lack of archaeological research on the Aksumite Empire, but it is likely that the weakening of the Aksumite state during this period also played a role in the absence of primary sources dated to this period.

Aksumite Territory In The 5th Century AD

It is important to emphasize that the territorial extent of the Aksumite Empire significantly shrank following the reigns of Emperor Ezana and Saizana in the early to mid-4th century AD. During this time, the Aksumites lost control over territories in Nubia and the Blemmyes (Beja) region to the east of Nubia, in addition to ceding lands in Southern Arabia to the Himyarites.

Nubia

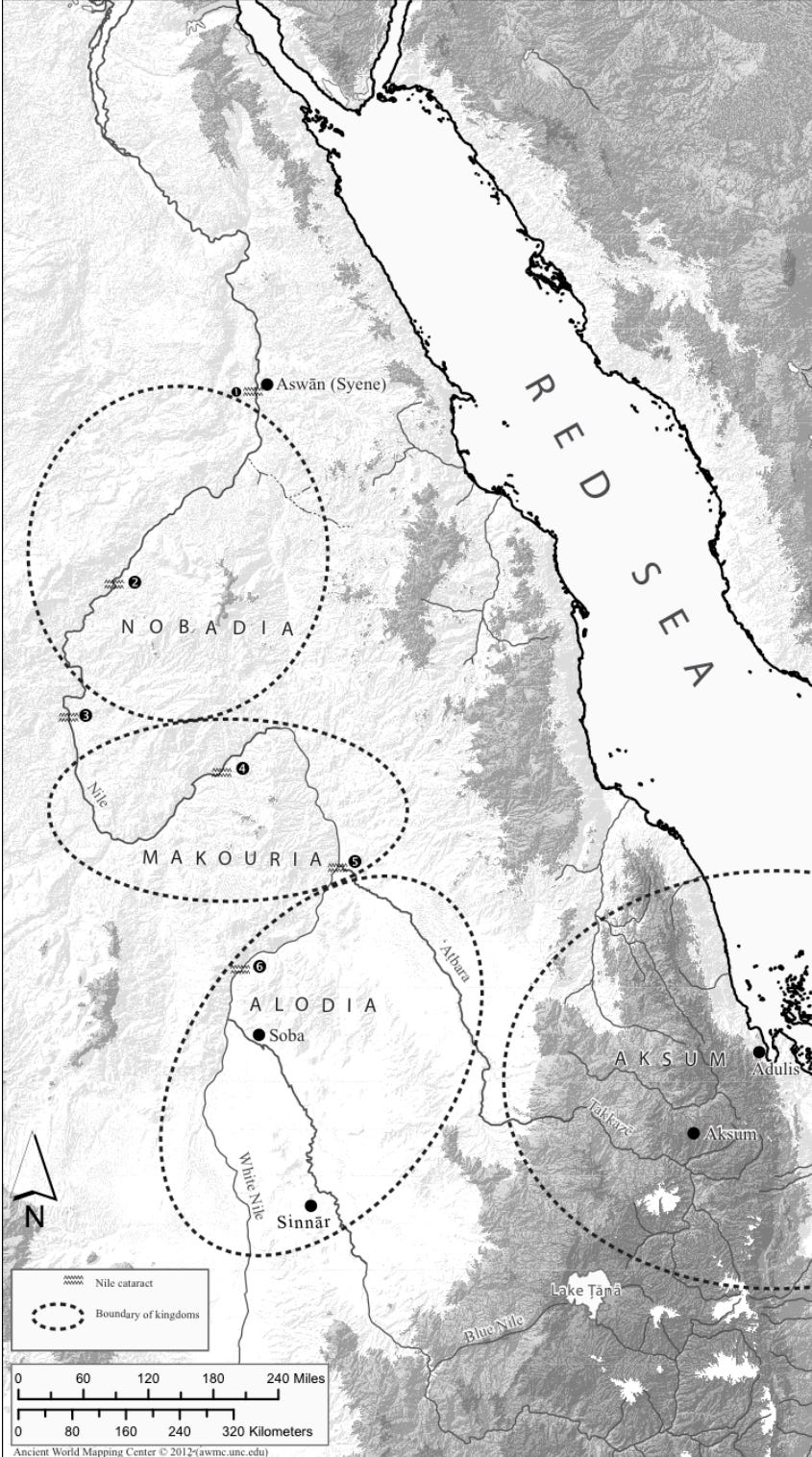

After the fall of Meroe, three kingdoms emerged: Nobadia (named after the Noba tribe), situated between the first and third Nile cataracts; Makuria, spanning from the third to the fifth cataract; and Alodia, extending from the fifth cataract to the lower Blue Nile1. These kingdoms began to take shape around 370 AD2, following the deaths of Emperors Ezana and Saizana of the Aksumite Empire.

These kingdoms, particularly Nobadia, were involved in wars (sometimes in alliance with the Blemmyes) against Rome3. However, the Aksumites are not mentioned in these conflicts, suggesting that they likely acted largely independently of the Aksumite Empire during this period.

Blemmyes/Beja

The Blemmyes were comprised of various Beja tribes and local kinglets during this period. While some tribes on the southern periphery, near the Aksumite Empire (such as the Suakin region), may have felt Aksumite influence, the northern Beja territories remained entirely beyond Aksumite control. In fact, some of these northern Beja tribes independently waged war against states like Roman Egypt.

Much of what we know about this era comes from the Roman historian Olympiodorus of Thebes, who visited Aswan and met with Blemmyes dignitaries4. He was granted access to several Blemmyes cities and documented their conflicts, including wars with Egypt and Nobatia. For example, he recounts a treaty signed between the Romans, the Blemmyes, and the Nubades (the people of Nobadia)5. Notably, the Aksumites are absent from these agreements, with only local representatives of the Blemmyes and Nubadians mentioned, suggesting that the Aksumite Empire had no direct control over the region.

South Arabia

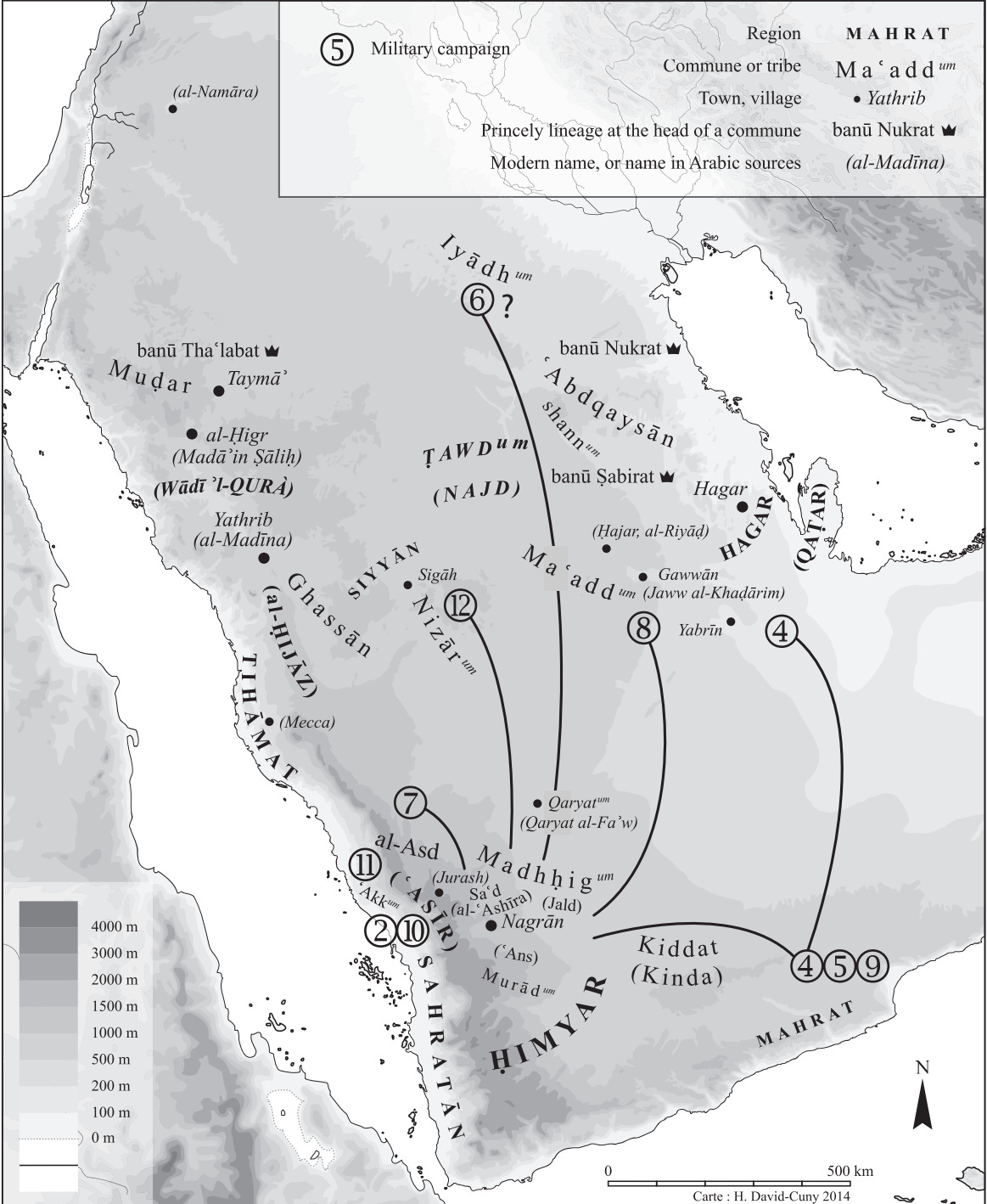

Scholars largely agree that Emperor Ezana and Saizana likely did not maintain control over any part of southern Arabia6. Aksumite influence in the region appears even less attested after their reign7, with no clear evidence of Aksumite presence until the time of Emperor Ousanas II (Emperor Kaleb’s father). By this period, southern Arabia had firmly come under Himyarite rule.

Furthermore, the rulers of Himyar during the 4th and 5th centuries styled themselves as “Kings of Sabaʾ, of Dhū-Raydān (Himyar), of Ḥaḍramawt, and of Yamnat”, signifying their dominance over all former South Arabian polities8. Himyar’s power extended even further north into “Arabia Deserta”, covering central Arabia, and by the 5th century AD, they expanded into coastal Arabia as well9. Notably, no historical sources from this era mention the Aksumites in the region, further supporting the likelihood that the Aksumites had no presence in southern Arabia at this time.

Roman Accounts Of The Aksumite Empire

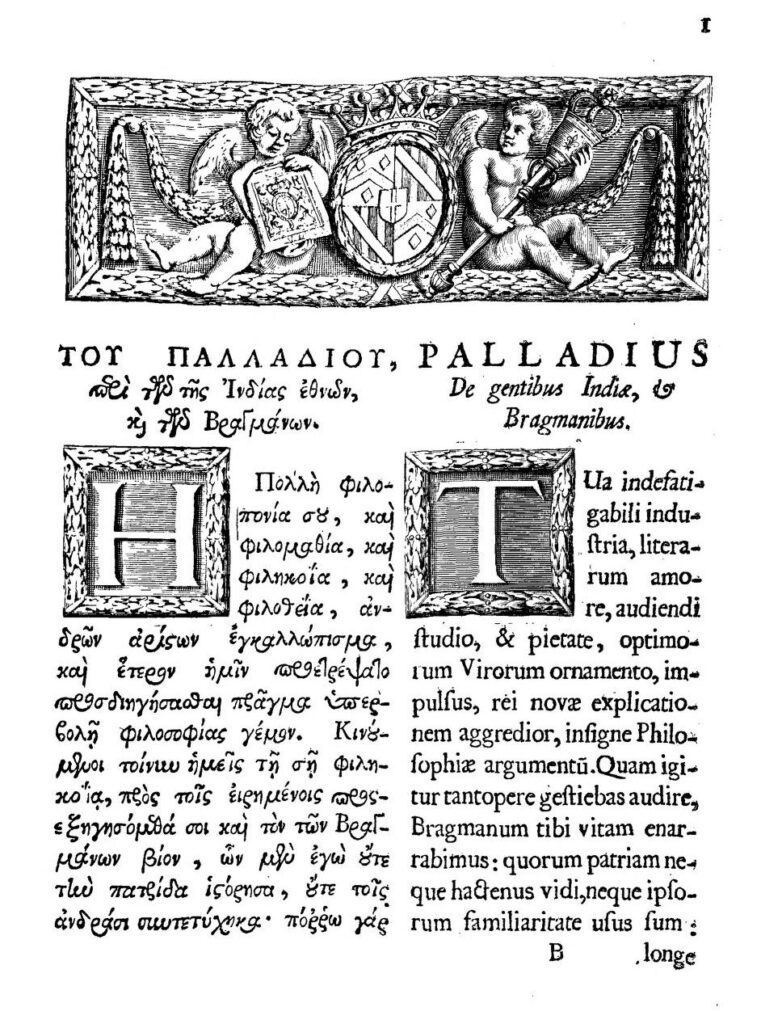

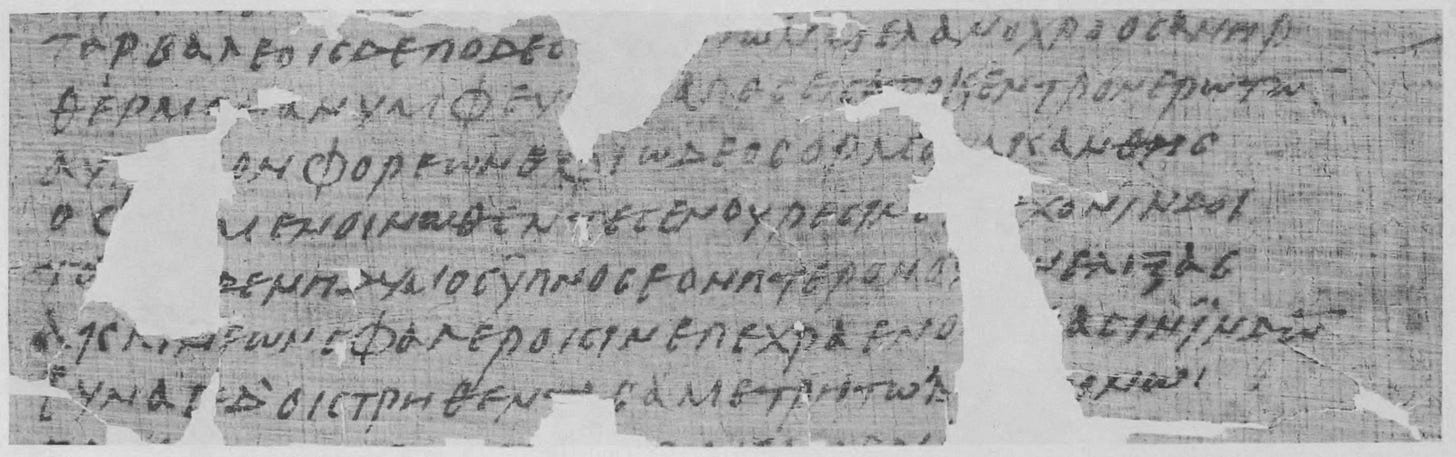

In the late 4th to early 5th century AD, the Aksumites are mentioned in a written work by Palladius of Galatia (~360–430 AD). In his account of the “Brahmans”, he describes a passage to India via the Red Sea (an already well-established trade route) and references both the Aksumites and Adulenians.

I have highlighted all the mentions of Aksum and Adulis in his work below:

Palladius himself only reached as far as Adulis, he gathered most of his information from a “skholastikos”/scholar who had travelled further to India.

Interestingly, Palladius refers to the Aksumite emperor as “Basiliskos Mikros” (Basiliskos meaning “minor king” or “chief” and Mikros meaning “small” or “insignificant”). This suggests a perception of Aksum’s declining power at the time. As previously discussed, both Nubian and Beja territories had fallen out of Aksumite control, along with South Arabia. It is also possible that centralized authority within the empire’s core had weakened, further indicating a period of decline.

Palladius’ mention of the “overseer” of the Adulenians suggests a degree of separation between the inhabitants of Adulis and the Aksumites, to the extent that they were identified as Adulenians rather than Aksumites. This distinction may indicate a level of local autonomy. Additionally, his reference to Aksumite traders being present in Taprobane, the classical Greek name for modern-day Sri Lanka, is plausible, as a century later, the explorer Cosmas Indicopleustes would make a similar observation10.

The Council Of Ephesus & Interactions With Jerusalem

In 431 AD, Emperor Theodosius II of the Eastern Roman Empire convened the Council of Ephesus, hosting significant theological debates with clergy from across Christendom. Notably, there is mention of bishops from India, which scholars widely agree was actually a reference to bishops from Aksum and Adulis11. Some scholars also hypothesise that a bishop from Adulis was present at the Council of Chalcedon, however this is disputed12. Lastly, communication between the Patriarch of Jerusalem & the Aksumite clergy is attested to in the late 5th century, when a bishop named Thomas was consecrated and sent to the Aksumite empire13.

Aksumite Middle Era – Emperors

Emperor Ouazebas (~370AD)

After the reign of Ezana, the next known emperor of the Aksumite Empire was Ouazebas, according to the historian and Aksumite coin experts Stuart Munro-Hay & Bent Juel-Jensen14. There is limited information about his reign, but coins bearing his name have been discovered beneath the largest Stele at Aksum. Scholars believe this might indicate that the Stele fell during his reign15. The exact circumstances of the Stele’s fall and the events during Ouazebas’s rule remain largely unknown, making his reign a subject of ongoing historical investigation. Interestingly during his reign, the reverse side of his coins had an inscription reading “May this please the people”16, possibly alluding to some sort of political strife in the empire.

Opinion: It’s likely during his reign that the formal secession of Beja & Nubian Territories occurred, possibly inducing a temporary state of anarchy or riots closer to the core of the Aksumite empire or even Aksum itself, hence the fall of the stele and the motto “May this please the people” on his coins.

Emperor Eon (~400?AD)

Following the turbulent reign of Emperor Ouazebas, Emperor Eon ascended to the throne. Similar to his predecessor, detailed records of his reign are scarce. However, his coinage has been found as far east as Yemen in al-Madhariba17, suggesting that Aksum had extensive trade connections during his rule. What distinguishes Eon’s coinage is the Greek inscription “Βασιλεύς Ἀβασινῶν”18 (Basileus Abyssinian /Habasinon), which translates to “King of the Abyssinians” or “King of the Habeshas”19, a notable change from the King of the Aksumites, which is found in earlier coins. Archaeologists & historians largely agree that he ruled after Emperor Ouzabes20.

Theory: Emperor Eon’s use of the term Abyssinian/Habesha likely reflected the consolidation of the Semitic tribes inhabiting the highlands of Eritrea and Ethiopia at the time. Since the late 2nd century AD, under Emperor GDRT, these tribes and their cities—Aksum, Yeha, Matara, Qohaito, Adulis, and others—were largely brought under a centralized authority. Over the centuries, this political unity fostered the emergence of a shared identity.

Initially, it was foreigners, particularly South Arabians, who referred to these groups collectively as Habesha. However, over time, the term may have been adopted indigenously, coming to represent the unified Semitized Highland communities that formed the core of the Aksumite Empire.

(Looking at what had occurred previously during the reign of Emperor Ouazebas, consolidation of identity in the Empire makes a lot of sense, as it would likely help in reducing tribalism and thus instability, especially at the heart of the empire)

Emperor Mehadeyis – The Warrior(~430AD)

After Emperor Ebana, Emperor MHDYS vocalized as Mehadeyis reigned21. This ruler is known primarily through the Aksumite coinage that features his name. The coins attributed to Mehadeyis includes both Greek and Ge’ez inscriptions, interestingly besides Emperor Wazeba, no other Emperor minted coins used Ge’ez22.

Particularly notable are the copper and bronze coins, which also bear the motto “In hoc signo vinces,” meaning “By this sign, you will conquer”23 or “by this victorious, by the cross” 24. This motto, which references the Christian cross, signifies the emperor’s dedication to Christianity and his warlike nature. The quote was also used previously by Emperor Constantine of the Roman Empire, and most likely drew inspiration from it.

In the Ge’ez inscription on the coin, the following is inscribed: “ngś mw’ mHdys” translates to “The Victorious King MHDYS”25.

Look at the combination of the iconic wheat branches (seen in multiple Aksumite coins) and a cross on one of Emperor Mehadeyis’ coins, one might envision this as a symbolic “icon” of the Aksumite Empire following its conversion to Christianity.

Historical References to Mehadeyis

The Dionysiaca, a Greek text from the 5th century by the Roman Egyptian poet Nonnus, spans 48 books and centres on the life of Dionysus and his war with the Indians. Throughout the poem, Nonnus frequently mentions Ethiopians, often conflating them with Indians. He describes these Ethiopians and a particular section of “Indians” as living east of the Nile and having black skin with curly hair26.

Within this epic poem, there is a mention of a warrior king named Modaios who inhabited the Ethiopian region. Scholars believe this might reference MHDYS, a figure noted for his warlike behaviour and Christian devotion, as evidenced by his coinage27. The inscription on his coins, “In this sign, you will conquer,” aligns with the characteristics of a warrior king deeply committed to the Christian faith mentioned in the poem.

As mentioned previously, bishops from the Aksumite Empire had travelled all the way to Ephesus (in modern-day Turkey) during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II – which coincides with the reign of Emperor Mehadeyis.

Two excerpts from the poem are as follows:

“(Dionysus) assigned a governor for the Indians, choosing the godfearing Modaios.” – New Evidence of King MḤDYS?, pg 205

“(Ares) took the form of the champion Modaios, more than all others unsated with battle, whose joy was joyless carnage, whom bloodshed pleased better than banquets” – New Evidence of King MḤDYS?, pg 206

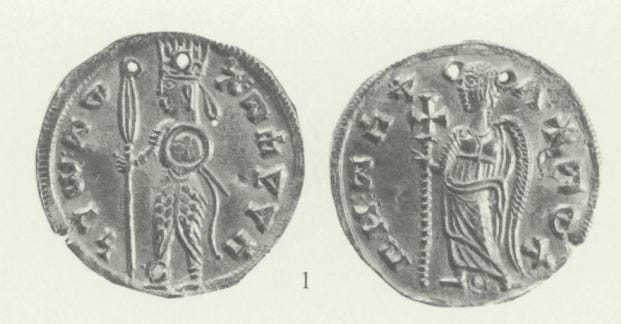

Unique Gold Coin of Mehadeyis

The two sides of the coin illustrate the dual aspects of Emperor Mehadeyis’s reign: his military prowess and his commitment to the Christian faith.

A unique gold coin featuring Mehadeyis was discovered, providing a rare and detailed depiction of the emperor, not found in any other Aksumite Coinage28. This coin is significant for several reasons:

- Obverse Side: The obverse side of the coin features a full-body portrayal of Emperor Mehadeyis, holding a shield in one hand and a spear in the other, dressed in official regalia, likely a type of armour. His right arm is adorned with three armlets, and a crown sits atop his head, from which a ribbon falls at the back. He is depicted wearing trousers with a tail-like object attached, reminiscent of the bull’s tail worn by Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs29. The end of a short sword is visible. This imagery emphasizes his role as a warrior and conqueror.

- Reverse Side: The reverse side of the coin depicts a female figure draped in a cloth, holding a long staff topped with a cross. She is adorned with wings on both sides of her shoulders. The inscription on this side reads, “By the cross, he shall conquer.” This coin bears a striking resemblance to those minted by Theodosius II of the Eastern Roman Empire around 420 AD, suggesting that Aksumite coinage was likely inspired by this design30. This depiction highlights Emperor Mehadeyis’s religious devotion and strong connection to Christianity.

Look at the striking similarity with the medieval Abyssinian Warrior above….

Emperor Ebana (~450AD)

After the reign of Emperor Mehadeyis, it’s likely Emperor Ebana ruled the Aksumite Empire31. Like his predecessors, specific details about his reign are limited. However, his coinage also bears the inscription “Βασιλεύς Ἀβασινῶν” (King Of The Abyssinians)32, indicating continuity in the royal title. Ebana’s reign is notable for the large number of coins that have been discovered, making him the emperor with the most gold coinage33. This abundance of coinage suggests a period of economic stability and extensive trade under his rule, it’s likely Emperor Ebana ruled for a long period of time34.

After the largely successful reigns of Eon and Mehadeyis, who likely consolidated power and stabilized the empire, it is not surprising that Emperor Ebana would follow their lead, ushering in a period of relative stability and increased commerce.

Emperors Neezol and Nezana (~470AD)

The reigns of Neezol and Nezana present an unanswered case in Aksumite history. These two names might refer to separate emperors, a dual reign or an emperor with two names35. One of the theories was that Nezana was the primary ruler and Neezol the secondary, with Neezol possibly becoming the primary ruler after his death36. Coins from Nezana & Nezool have been dated to the late fifth to early sixth centuries37.

Coinage from both rulers also includes the inscription THEOU KHARI “By The Grace Of God”38, besides obvious religious devotion, this possibly might allude to the political turmoil occurring up north around this time (476AD – the fall of the Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustus & general turmoil in the Roman Empire), which no doubt troubled the royal court as they were a Christian Empire who had long established trade and political relationships with the Aksumite Empire.

It was during the period of Emperors Neezol/Nezana that the nine saints came from the Roman Empire39.

Emperor Ousas (~500AD)

The last known emperor of this period is Ousas also known as Ousanas II, who reigned from the late 5th century to the early 6th century. Although detailed historical records are sparse, his coinage provides some insights. The inscriptions on his coins read “Ousas King” and “By the Grace of God”40. Scholars suggest that Ousas might have been the father of the famous Emperor Kaleb, with Ousas’s alternative name being Tazena in traditional records41.

There are three different names in the coinage: Ousas, Ousana & Ousanas. Scholars used to speculate that these were three separate Emperors but now most think it’s one42.

Emperor Ousas may have led a military expedition into South Arabia towards the end of his reign, as scholars state that King Ma’dikarib Ya’fur (~519AD), was a puppet of the Aksumites43. This is supported by an Indigenous manuscript Qese Gebez Tekle Haimanot of Aksum, which states the following:

“Ezana, whose throne name is Tazéna, went in the direction of the East and fought against India. He defeated them, killed them, captured many prisoners, and took abundant booty. He subdued them and made them pay tribute.” – Qese Gebez Tekle Haimanot of Aksum (Source: Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 123)

- Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa, pg 155. ↩︎

- The Rise of Nobadia: Social Changes in Northern Nubia in Late Antiquity, pg 19 ↩︎

- The Fragmentary varia, pg 323 ↩︎

- The Fragmentary varia, pg 199 ↩︎

- The Fragmentary varia, pg 323 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 79 ↩︎

- Axum by Kobishchanov pg 80 ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 127. ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 138 ↩︎

- The Throne Of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 23 ↩︎

- A history of the Holy Eastern Church, pg 220 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 110 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 110 & 111 ↩︎

- Aksumite Coinage by Stuart Munro-Hay & Bent Juel-Jensen, pg 74. ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 109 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 192 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 108 ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford, pg 76. ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 111 ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 78 & Aksumite Coinage by Stuart Munro-Hay & Bent Juel-Jensen, pg 74. ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 81 & Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 78 & Aksumite Coinage by Stuart Munro-Hay & Bent Juel-Jensen, pg 74. ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilization, pg 188 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 81 ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West , pg 84. ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 42 ↩︎

- New Evidence of King MḤDYS?, pg 201 ↩︎

- New Evidence of King MḤDYS?, pg 206 ↩︎

- A New Gold Coin of King MḤDYS of Aksum, pg 276 ↩︎

- A New Gold Coin of King MḤDYS of Aksum, pg 276 ↩︎

- A New Gold Coin of King MḤDYS of Aksum, pg 276 ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 78 & Aksumite Coinage by Stuart Munro-Hay & Bent Juel-Jensen, pg 74. ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 86 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 110 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 110 ↩︎

- Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford by Wolfganghan & Vincent West, pg 12. ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 116 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, pg 111 ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 147 ↩︎