Introduction

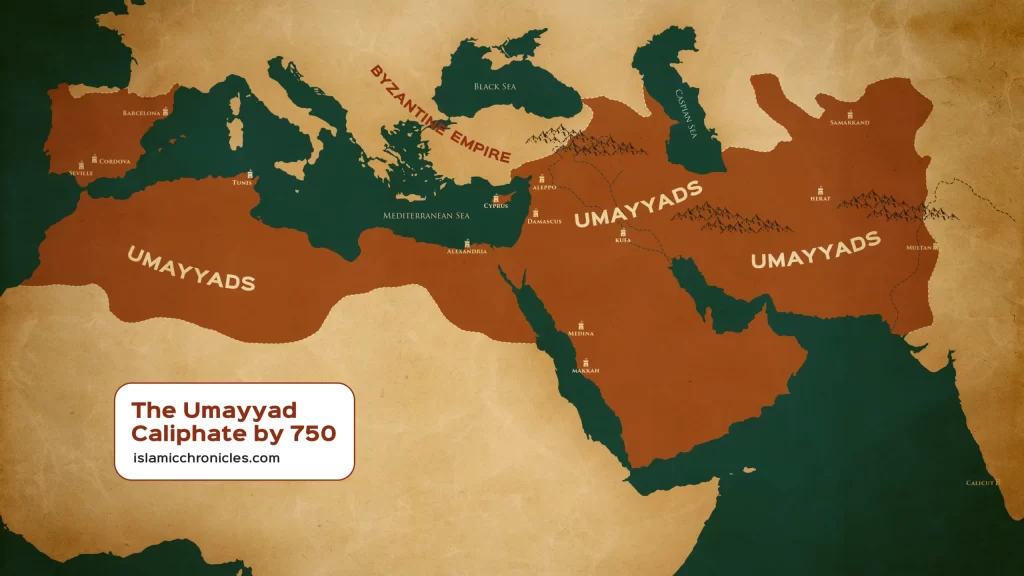

Around 548 AD, following the death of Emperor Gebre Meskel, the Aksumite Empire entered a prolonged period of decline, affecting various aspects of the empire, including its economy, culture, and military. This decline led to widespread unrest and the loss of significant territories. One of the key factors driving this decline was the emergence of a new religion in the Arabian Peninsula (Islam), which rapidly spread across the Middle East and into Egypt, effectively severing the Aksumite Empire’s access to Mediterranean markets.

This article delves into the challenges faced by the Aksumite Empire during these turbulent times, beginning with an exploration of Nubia in the north and then moving to Arabia in the east. Despite the mounting pressures, the Aksumite Empire did not succumb quietly; it fiercely defended itself and even launched counteroffensives against formidable adversaries, fighting until the very end.

Nubia

As previously discussed, the Nubians and Kushites had been under Aksumite sovereignty since the conquest of Meroe by Emperor Ousanos in the 3rd century AD. Although there had been several rebellions, the region largely remained within Aksum’s sphere of influence. However, this dynamic began to shift by the mid-6th century, with the emergence of three new kingdoms in the region: Nobatia in the far north with the capital Faras, Makuria in the centre with its capital at Dongola, and Alodia in the south with its capital at Soba1.

Even as early as the mid to late 5th century Nobatia was already showing signs of secession.2 It was likely sometime after Emperor Kaleb’s reign3, after his conquests in Himyar, possibly during the feud between Gebre Meskel & Israel that these three Nubian kingdoms fully emerged.

Wars With Nubia (6th & 7th century AD)

During this formative period for the Nubian kingdoms in the north, both a religious and military battle was occurring with the Aksumites, we have attesting to both. For example, Historian Sergew Hable Selassie mentions that the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church in Alexandria, Egypt who was named Issac (between 686-689AD) had sent a letter to the Aksumite Emperor & the Emperor of the Nubians, asking them to cease hostilities in hopes of reaching peace in the region4.

Religious Wars

In terms of religious battles between the Nubian states and the Aksumites, we know that all three Nubian kingdoms had converted to Christianity around 540AD, with the kingdoms of Nobatia and Alodia being Jacobites while in Makuria the Melkites had greater power5. This led to not only conflict between these three Nubian kingdoms but also religious conflicts with The Aksumites as they believed in the Monophysitic nature of Christ.

The loss of the Nubian region in the 6th century undoubtedly had a profound impact on the economic stability of the Aksumite Empire. During the 4th and 5th centuries, Aksum’s full control over Nubia facilitated flourishing trade with Egypt, allowing the empire to export and import goods freely. However, as Aksum lost direct control over Nubia and engaged in conflicts with the three Nubian kingdoms, trade between the two regions inevitably declined. When trade did occur, it was subjected to taxation. This economic strain was further exacerbated by the loss of Aksum’s control over South Arabia to the Persians in 575 AD. As a result, the Aksumites no longer had control over the crucial trade routes up the Red Sea to Egypt and the Mediterranean, further weakening their economic position.

Eventually, the Jacobite faction did win the religious war8, however, Makuria would annex Nobatia by the early 7th century AD9.

The Last Great Crusade (8th Century AD)

In 748AD, following the conclusion of the Nubian civil wars, peace was established between the Aksumites and their neighbours. This newfound alliance culminated in a joint military campaign against Umayyad-controlled Egypt. The conflict arose when Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad caliph, imprisoned the Orthodox patriarch, aiming to extort money and suppress his communications with King Cyriacus of Makuria10. In response, the Nubian states (led by King Kyriakos) and the Aksumites11 assembled a formidable force of approximately 100,000 men and camels, supported by over 10,000 horses. Together, they crossed into southern Egypt, launching a successful invasion that saw them capture and plunder several cities. Reaching as far as modern-day Cairo12. The swift and decisive campaign pressured the caliph to release the patriarch to halt further hostilities. With the patriarch’s release, the war came to an end, and the combined forces of Nubia and Aksum returned to their respective territories.

Coptic Orthodox Perspective

Aksumite Perspective

The alliance between the Nubian states and the Aksumites persisted into the 9th century, with both forces once again engaging in a war against Egypt in the middle of that century13. This is substantiated by the following excerpt from the primary source Patriarchs of Alexandria:

14 Years of War which impeded most if not all trade with Egypt and thereby most of the Mediterranean, alludes to a horrible economic situation for both the Nubians and the Aksumites in the 9th century, which is yet another indication of the fall of the Aksumites.

Arabia & The Rise Of Islam

Some scholars believe the church depicted in the coins of Armah depicts the Holy Sepulchre14 as a tribute, as it had been captured in 614 AD.

As previously discussed, by 575 AD, Southern Arabia was no longer under Aksumite suzerainty, following the Persian conquest of Himyar and the defeat of Abraha II’s remaining forces. The Persians not only conquered the region but also committed acts of genocide against many Aksumite civilians. Despite this loss, the Aksumites maintained a formidable naval presence in the Red Sea during the late 6th and 7th centuries AD. In 640 AD, Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab of the Rashidun Caliphate dispatched a naval force under Admiral Alkamah to confront the Aksumites, prompted by reports of attacks on Muslims along the northern coast, likely between Massawa and Adulis. However, this naval detachment was utterly defeated, deterring any further attempts by Umar to challenge the Aksumite navy during his reign15. The excerpt is as follows:

Relations With Prophet Muhammed (570AD-632AD)

In 570AD, Prophet Muhammed was born in Mecca, this was right when the Aksumite forces were warring with the Persians in Himyar, & only just a few decades after the Aksumites had attempted to invade Mecca, therefore it’s no surprise Muhammed knew about the Aksumites and throughout his life would be in contact with them. Throughout his childhood, his nurse Umm Ayman was of Aksumite Origin (claimed to be a slave, most likely sold from the southern regions of the Aksumite Empire), she helped deliver the birth of Prophet Muhammed, and with him throughout his childhood and adult years, referring to her as a “mother after my mother”16.

According to a Chinese text translated from a Persian manuscript detailing the life of Muhammad, it describes a journey taken by Muhammad’s grandfather to attend the coronation of Emperor Saifu. At the time of Muhammad’s birth, the reigning emperor was Saifu, who was the grandson of Emperor Kaleb. The following is an excerpt from the text:

“The great king, your grandfather, was a benevolent king, and his grandson is a holy sovereign, who breaks off with flatterers and follows what is right, avenges the oppressed and, acting upon right principles, administers the law equitably. Your servant is the superintendent of the sacrifices in the sacred precincts of the True God, a son of the Koreish, who, hearing that your Majesty has newly received the great precious throne, has come to present congratulations.” – Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity pg 92.

Emperor Armah, who ruled during the late 6th and early 7th centuries AD, played a significant role in early Islamic history. In 613 AD, when Prophet Muhammad called for the First Hijra (migration) to the Aksumite Empire to escape the persecution inflicted by the dominant tribe of Mecca (The Quraysh), he chose the Aksumite Empire because it was a strong and just empire that would likely offer refuge to the oppressed. In this first migration, Muhammad sent eleven men and four women, including Uthman ibn Affan, who would later become the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate17. They arrived at the port of Adulis and journeyed to the royal court at Aksum, where they met Emperor Armah, who graciously promised them safety and asylum.

According to Islamic Sources, After Emperor Saifu there was one other unnamed ruler, who had one brother who completed a plot of assassination against him and sold the rightful ruler’s only son named Amrah to slavery. Later on, the royal court would find him Amrah and reinstate him to the throne.

An Interesting Video that describes the Islamic perspective of Emperor Amrahs life is the following:

A year later, rumours spread that the Quraysh had ceased their persecution of Muhammad’s followers, prompting the refugees to return to Mecca. However, upon their arrival, they discovered that these rumours were false, and they were forced to flee once again to the Aksumite Empire, this time with a larger group of 63 men and 18 women in 616 AD18. They were led by Jaafer Ibn Abi Talib.

Alarmed by these developments, the Quraysh nobility sought to negotiate with the Aksumite royal court to secure the return of the refugees for prosecution. They sent a delegation led by Amr bin Aas, who brought lavish gifts to sway the Aksumite court. Emperor Armah granted them an audience, where the delegation falsely claimed that the refugees were criminals who needed to be sent back for punishment. Sensing the need for clarity, Emperor Armah summoned Jaafer Ibn Abi Talib to explain the situation. Jaafer eloquently defended their case, explaining that their people had been enlightened by Prophet Muhammad, who had guided them away from idol worship towards a monotheistic faith. He detailed how the Quraysh persecuted them for these beliefs.

Moved by their plight and their commitment to a monotheistic belief, Emperor Armah, with deep sympathy for the persecuted people whose only “crime” was their faith, decided not to hand them over to the Quraysh, ensuring their safety in the Empire.

The Speech given by Jaafer Ibn Abi Talib is as follows:

Around 528AD, Muhammed requested for his followers to return and sent messengers to dispatch this information to Emperor Armah19, when Emperor Armah received this message he allowed them to return back. Muhammed would continue to respect Emperor Amrah, with the following dialogue showing the warmness shared between each figure:

Emperor Amrah ordered the use of two ships for the refugees’ return. However, only 16 out of the original 80+ decided to go back. The rest settled in Negash, Tigray20. Which is the oldest settlement of Muslims in Africa and the World outside Arabia.

Around 630AD, Emperor Amrah died21. Before Muhammed’s death in 632 AD, it said that Muhammed prohibited any Jihiads (War against non-believers) against the Aksumites unless they were on the offensive22.

It’s believed in Islam that Emperor Amrah had converted in secrecy to Islam and that Muhammed had prayed the Janazah (Funeral Prayer) upon Amrah’s death. The validity of this statement is however questionable, the Emperor didn’t officially convert publicly & this is proven by the Christian crosses inscribed on coins during his reign. There is still a slight possibility that he had converted in private, with the royal court quickly stamping down any rumours…

Sanctions In Jeddah (7th Century AD)

Although Muhammad had instructed his followers not to attack the Aksumites, several skirmishes occurred both during his lifetime and after his death. The Aksumites had established a commercial presence off the coast of Jeddah, but in 631 AD, Muhammad ordered his admiral to remove the Aksumite ships and presence from the area23.

This marked one of the earliest instances of economic sanctions against the Aksumites, a factor that would contribute to the empire’s eventual decline centuries later.

As previously mentioned, the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, Umar Ibn Khattab, attempted a naval expedition in 640 AD to halt Aksumite ships from allegedly attacking Muslims near the Nubian coast. The expedition failed, and the Aksumite presence in the Red Sea remained unchallenged.

Also in 651 AD, the Aksumites attacked parts of Arabia, while the Nubians attacked Rashiduan Egypt, forming a Christian alliance24.

The Sacking Of Adulis & Beja Invasions (7th & 8th Century AD)

In 702 AD25, following earlier economic sanctions, Aksumites responded with an expedition to Jeddah. Though not directly, they likely permitted around 83 Abyssinian pirates (likely referring to ships) to loot and pillage Jeddah as retaliation26. This led to further sanctions against the Aksumites, with the Umayyad Caliphate annexing the Dahlak Islands and attempting to invade Adulis, which was still the most crucial port of the Aksumite Empire. Although the invasion was repelled, the city was still sacked27. The importance of this set of events can’t be understated, according to Professor Daniel Habtemichael, around 70% of all coinage in the region originated from Adulis28. This sacking likely didn’t result in the complete destruction however, the cause of the destruction of Adulis is not agreed upon by scholars, with them attesting to fires, while others a great flood/tsunami29.

Even though Adulis wasn’t captured, its sacking & the capture of the Dhalak Islands heavily impeded trade within the Aksumite Empire, this was the beginning of the decline of Adulis as an influential port city & commercial hub. From this point on, the port of Badi (Massawa, which was controlled by Arabs) started to become the primary trading port in the north of Abyssinia30.

The Beja Territories in Sudan became tributary states of the Ummyaid Caliphate (paying a hundred camels/300 dinars yearly)31, and this is the conditions under which Badi started prospering as a trading port, the Bejas were slowly pushed deeper southwards into Aksumite territory throughout the 7th century AD32, by the end of the 8th century AD Beja tribes were making incursions into the highlands of Eritrea, particularly Hamasien33.

It is likely that in the late 8th century AD, the mass migrations of Aksumites from the northern peripheries, particularly Eritrea, began. These migrations would move large populations southwards continuing the semitzation of southern regions below Lasta.

Emperors From 530AD-820AD

Establishing an accurate lineage after Emperor Kaleb is challenging due to the scarcity of sources that reference emperors whose names can be linked to coinage or other physical evidence. Aside from emperors like Israel and Amrah, there is little information available about the other rulers of this period. Scholars theorize that by the late 7th century AD34 Aksumite Coinage stopped being minted, with Emperor Hataz, being the last.

Coinage Of Aksumite Kings Between 6th century AD – 7th century AD, unfortunately besides these coins not much is known about any of the Emperors, besides of course Israel & Armah. Which I have both covered.

After coins stopped being minted, it became considerably more difficult to understand the timeline of Emperors however certain royal lineages exist traditionally and Historian Sergew Hable Selassie has outlined the following list of Emperors from the 7th & 8th century AD37.

- Zeray – Eklewudem – 623 to 633

- Germay – Asfar – 633 to 648

- Zeray II – Zirgas, or Girma Sor – 648 to 656

- Zirgas – Digna Michael – 656 to 677

- Ekle – Bahr Ekil – 677 to 696

- Hizba Sion – Gum – 696 720

- ? – Asgomgum – 720 to 725

- ? – Latem – 725 to 741

- ? – Telatem – 741 to 762

- Adegosh – Lul Seged – 762 to 775

- ? – Ayzur – half a day

- Didim – Almaz Seged – 775 to 780

- ? – Wudemdem – 780 to 790

- Dimawudem – Wudem Asfere – 790 to 820

Bibliography

- The medieval kingdoms of Nubia, pg 24 ↩︎

- The Rise of Nobadia: Social Changes in Northern Nubia in Late Antiquity, pg 35 ↩︎

- Aksum and Nubia, pg 155 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 193 ↩︎

- Ancient And Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, pg 177 ↩︎

- https://www.everyculture.com/Africa-Middle-East/Jacobites-History-and-Cultural-Relations.html ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Melchites ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 194 ↩︎

- The medieval kingdoms of Nubia, pg 7 ↩︎

- The medieval kingdoms of Nubia, pg 73 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 197 ↩︎

- The medieval kingdoms of Nubia, pg 73 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 208 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 91 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 192 ↩︎

- https://muslimhands.org.uk/latest/2023/10/black-history-month-2023-celebrating-our-sisters-umm-ayman-ra ↩︎

- https://madainproject.com/migration_to_abyssinia ↩︎

- https://www.al-islam.org/restatement-history-islam-and-muslims-sayyid-ali-asghar-razwy/two-migrations-muslims-abyssinia ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 186 ↩︎

- Layers of Time A History of Ethiopia, pg 43 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 188 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 191 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 191 ↩︎

- The Power of walls by Friederike Jesse, pg 132 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity , pg 195 ↩︎

- Islam in Ethiopia by J. Spencer Trimingham, pg 48 ↩︎

- Arab seafaring in the Indian Ocean in ancient and early medieval times, pg 54 ↩︎

- Modelling the Local Political Economy, pg 254 ↩︎

- The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis, pg 119 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 196 ↩︎

- A History of the Arabs in the Sudan, pg 164 ↩︎

- Islam in Ethiopia by J. Spencer Trimingham, pg 49 ↩︎

- Islam in Ethiopia by J. Spencer Trimingham, pg 49 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity , pg 195 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity , pg 89 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity , pg 89 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian history to 1270AD, pg 203 ↩︎