Yeha, dating from 800 BC to 100 BC, marks the dawn of civilisation in northern Ethiopia. As the heart of the pre-Aksumite period, Yeha laid the foundation for the rise of the Aksumite Empire with its remarkable architecture and cultural achievements.

Introduction

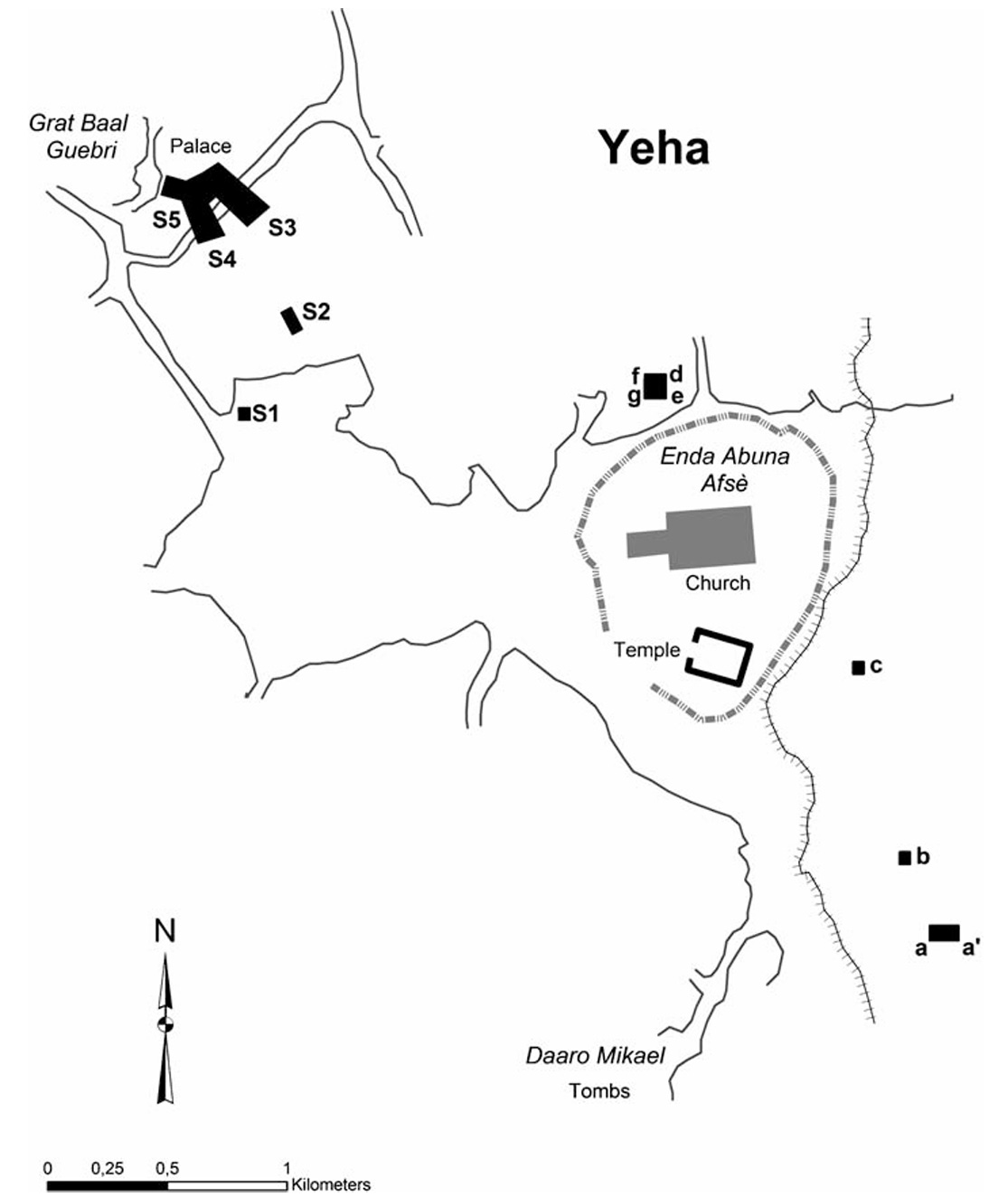

Yeha/ይሐ, situated in north-central Tigray, Ethiopia, is a site of profound historical significance, representing the northern Horn of Africa’s most impressive archaeological landscape during its time. Dating back to the early to mid-first millennium BC, Yeha’s importance is established through its well-preserved monumental structures and artifacts, which exhibit strong resemblances to its eastern neighbours, the Sabaeans, while also having unique characteristics indigenous to the region. There are three significant pre-Aksumite structures/sites located at Yeha, namely:

- The Great Temple of Yeha

- The palace at Grat Be’al Gebri

- The Necropolis at Daro Mikae

The word Yeha comes from an inscription found at Addi Akawah, in Tigray (close to where The Great Temple is located), this inscription refers to a great temple named Yeha. The inscription roughly reads as follows:

/

The Great Temple of Yeha

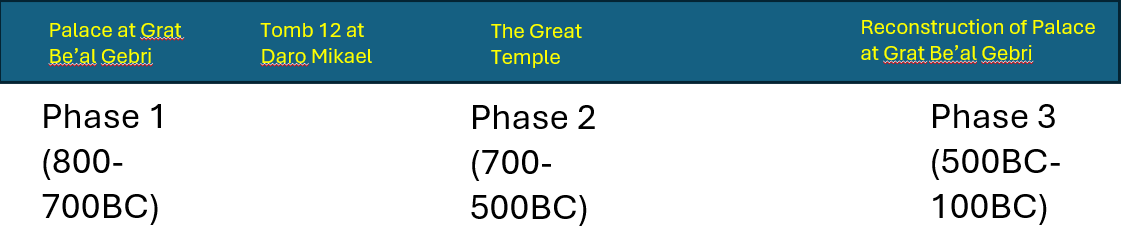

The Great Temple is a cornerstone of Yeha’s archaeological significance, exemplifying architectural styles and construction methods similar to those in southern Arabia at that time. Its main purpose is deemed to be a place of worship for Almaqah1, which was the southern Arabian moon god. Beyond its religious purpose, the temple also represented the social-political stature and technological achievements of its creators. Although researchers initially estimated the temple’s age to be 500 BC, it has since been revised to 800 BC2. Before the creation of the temple, a settlement is thought to have existed in the surrounding area.

Almaqah is associated with the Ge’ez word “ኣምላኽ” (ahmlak), which means “god” and is still used in modern Tigrinya and Ge’ez. This is likely because the original word was adapted during the conversion to Christianity in the 4th century AD, which coincided with the Aksumite period.

Historical Context and Excavations

Extensive archaeological excavations have revealed much about the temple’s structure and history. Initial digs were conducted in the 1960s, with further significant excavations taking place between the 1970s by the Ethiopian Institute of Archaeology under Francis Anfray’s direction, and again in the 1990s by a French expedition led by Christian J. Robin . These efforts were complemented by a comprehensive area survey in 1974 by an American expedition under Joseph W. Michels, providing a broad archaeological context for Yeha and its surroundings 3.

Architectural Features and Comparative Analysis

The rectangular structure was 18.6 x 15.0 m and with a height of up to 13 meters high 4, the structure consisted of rectangular blocks of sandstone. The Great Temple originally featured a large porch with six rectangular pillars, a design element that finds parallels in structures at Marib and Baraqish in southern Arabia. Upon entrance, the double wooden doors opened to reveal a narrow passageway leading to the temple5.

The Great Temple, known for its impressive preservation, owes much of this to its transformation into a church dedicated to Abba Afse, one of the nine Habesha saints. This adaptation, believed to have occurred around the 6th century AD, not only preserved the structure but also integrated it into the ongoing religious practices of the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian community. The temple hosts major annual religious festivals, highlighting its continued significance as a sacred site6.

The interior organization of the temple was meticulously planned with five aisles divided by square pillars, with the central area open to the sky. This architectural choice is echoed in the design of early Habesha Christian churches, suggesting continuity and adaptation of architectural forms over time7.

The eastern end of the temple was distinctly sectioned into three rooms, and the entire floor was laid with sandstone panels, directly atop the natural rock. A notable feature within the temple was its drainage system, designed to prevent flooding by channelling water to a hole in the southern wall8.

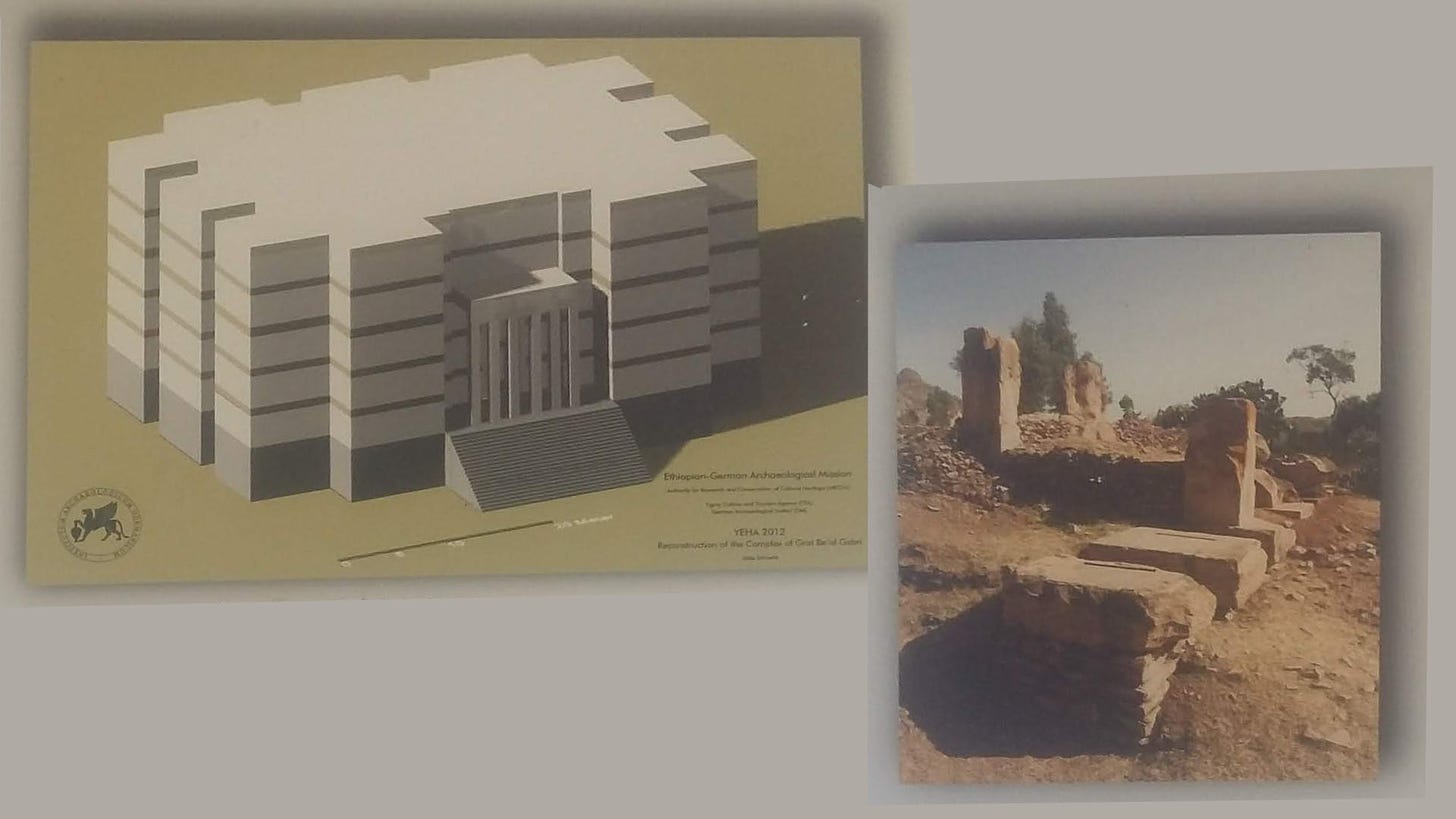

Grat Be’al Gebri: Elite Architecture

Another significant discovery at Yeha is Grat Be’al Gebri, often referred to as a ‘palace’. This ancient elite building further underscores the complexity and sophistication of pre-Aksumite society in Yeha. The structure likely served as a residential and administrative hub for the ruling elite, playing a crucial role in the management and governance of the local populace.

Architectural Features

The building originally spanned at least 46 x 46 meters and included a 4.5-meter-high podium, This podium housed an interior chamber system9.

The primary entrance was marked by a six-pillar roofed porch, the bases of which, along with some pillar remnants, remain today. Behind this grand entryway lay a large gate leading into a hallway, which in turn opened into a corridor that bisected the building. This corridor provided access to various rooms, although the specifics of these rooms remain less documented due to the building’s deteriorated condition10.

Grat Be’al Gebri, showcases two principal phases of construction, each illustrating different architectural techniques and cultural influences. Initially, this monumental building was erected with a distinctive South Arabian influence, featuring a stepped podium and a front porch supported by pillars. Unfortunately, this initial structure met its demise through a catastrophic fire, leading to its destruction11.

Subsequently, a second building phase ensued where a new structure was built directly over the ruins of the first. This new construction utilized rougher wall techniques, possibly incorporating the Aksumite ‘monkey-head’ technique, known for its timber framing and use of rubble stones and mud. Stratigraphic test pits at the base of the podium further revealed that the site had been occupied even before the construction of the original building12.

Grand buildings like the one in question were present during the Aksumite times, as well as in later periods such as the Zagwe period. This particular structure could have been the first elite building created by the Habeshas, and it might have served as a palace for a ruler or king of that time.

Other Artifacts found

Excavations and tests in areas surrounding Grat Be’al Gebri have yielded a range of artifacts. Notably, ceramic findings from the second phase of the building’s use include a variety of wares such as red coarse ware, black polished coarse ware, and several types of fine wares, reflecting the rich material culture of the inhabitants.

The Necropolis: A Glimpse into Elite Pre-Aksumite Burial Practices

Adjacent to these monumental buildings is the necropolis, a large burial site at Daro Mikae, where tombs of the elite have been uncovered. These shaft-tombs provide invaluable insights into the burial customs, social hierarchies, and religious beliefs of the period. The artifacts and tomb constructions found here highlight a society that placed significant emphasis on the afterlife and its preparation.

Professor Rodolfo Fattovich suggested a date for these tombs around the mid-first millennium BC, with evidence of continued use into the late first to early second millennia AD13.

It is believed that the tombs found in Yeha were used for the rulers of the surrounding areas, maybe even the elusive D’MT kingdom. It is interesting to note that similar subterranean tombs were also used for Aksumite rulers at Aksum. This suggests that the practice of building such tombs may have originated in Yeha and spread to other regions.

Discoveries at the Necropolis of Abiy Addi, Yeha

Survey and Excavations

In the autumn of 2009, a joint Ethiopian-German archaeological team conducted a survey in the area of Yeha, specifically on the hill slope of Abiy Addi, located opposite the ancient Yeha settlement. This survey led to the discovery of a necropolis with visible signs of burial sites, Local residents shared with the team that one of the tombs contained a shaft and a staircase, indicating the presence of subterranean burial chambers14.

Further excavation in the spring of 2010 revealed six rock-cut tombs, each featuring a 2.5-meter-deep vertical shaft of rectangular shape, with one grave chamber at each of the narrow ends. The entrances to these chambers were originally sealed by rectangular stone panels, though these were missing in most cases by the time of discovery. The tombs were also capped with stone panels at the surface and surrounded by a mound of stone rubble15.

Tomb Structure and Contents

The chambers varied in size, with some extending up to 4 meters in length and reaching almost 1.2 meters in height. Unfortunately, most had been looted. The excavation team did find dislocated skeletal remains and fragments of clay vessels among other grave goods such as beads16. Notably, one of the chambers contained a burial from the sixteenth century AD, illustrating the continued use of the site across millennia.

Cultural Significance

The artifacts discovered, such as bronze seals featuring Sabaean motifs like the ibex associated with the deity Almaqah and Sabaean script, highlight a blend of local and South Arabian traditions. This blend is unique in that such objects have no direct parallels in South Arabia, indicating a localized adaptation of external influences17.

Interestingly, rock-cut tombs of this type appear in the archaeological record of Yeha before similar structures were found in South Arabia, suggesting that such burial practices were indigenous to the region before the rise of the Ethio-Sabaean kingdom18.

Brief Timeline Of Events & Interaction with Periphery states

Pottery resembling the style found in Yeha, initially found mostly in local areas during Phase 1, expanded in distribution during Phase 2. This expansion included not only sites in Tigray but also in Akkele Guzay, suggesting increased interaction and cooperation between the populations of these regions. In contrast, the ancient Ona sites in Asmara preserved their unique ceramic traditions, though fragments of Ona jars have been discovered in Akkele Guzay and Tigray. This indicates that trade was possible, even though the Ona sites likely had their distinct culture and possibly their own elites19.

Conclusion

Yeha is one of the most famous and researched sites from the pre-Aksumite period. It features several notable sites and was likely the capital of development during that time. Unfortunately, not much archaeological work has been completed in the region, so many questions remain unanswered. However, new discoveries are guaranteed to occur, and our knowledge of the area is still in its infancy. It’s clear that Yeha was one of the first signs of hierarchical Habesha societies, organizing to create places of worship, living and burial.

Bibliography

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 24 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 26 ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 276) ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 24 ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 148). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 147). ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 26 ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 148). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 150). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 151). ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 278 & 279) ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 278 & 279) ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 153). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 153). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 153). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Saba and DMT – New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia by Sarah Japp, Iris Gerlach, Holger Hitgen & Mike Schnelle (pg, 154). ↩︎

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich (pg, 285) ↩︎