During the dawn of written history, several towns & cities emerged in the Akkälä Guzay region, such as Qohayto, Käskäse, Täḳwända, and Addi Kramatən, facilitating trade between Adulis & Yeha.

Introduction

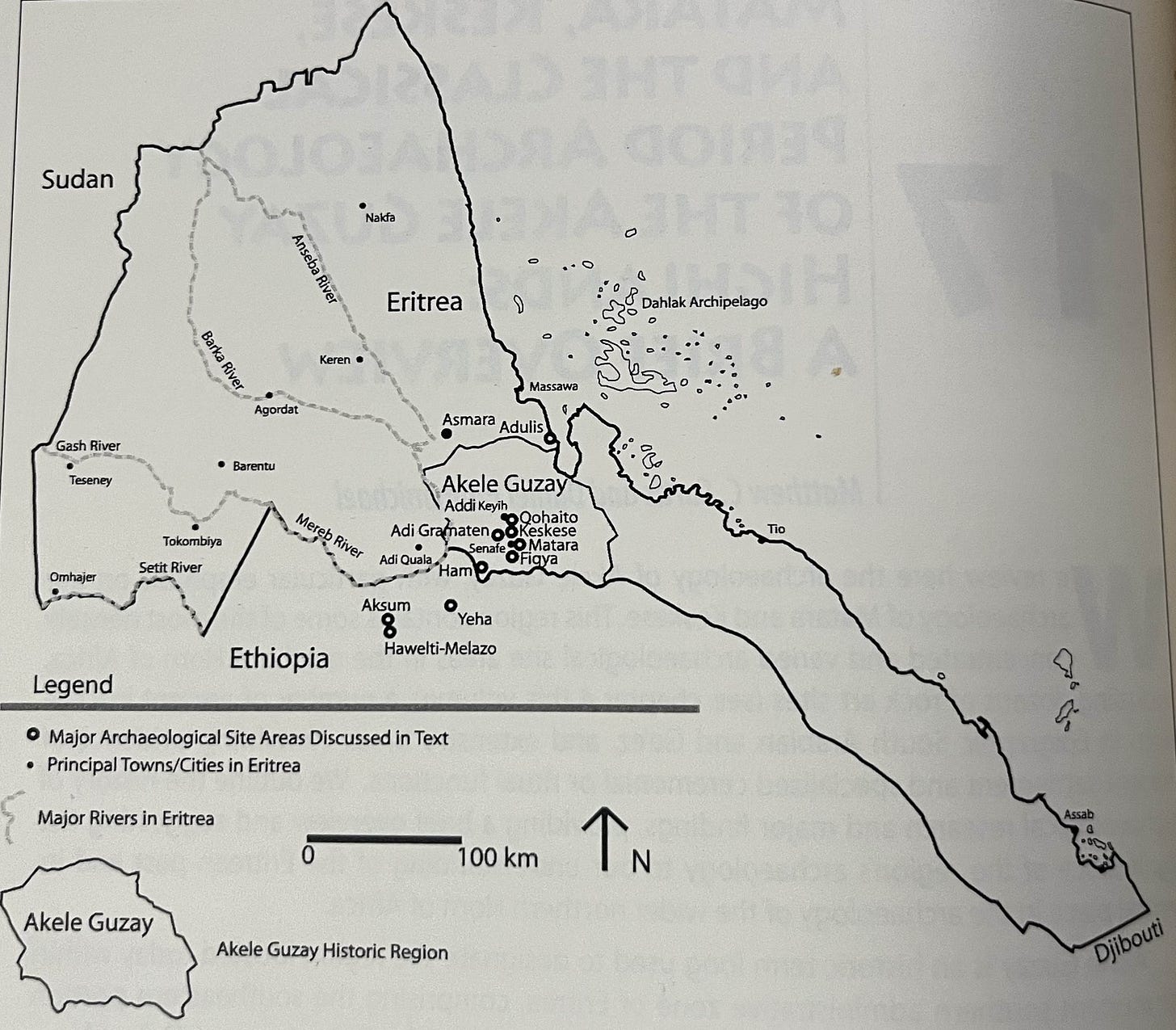

Although archaeological work in Eritrea is still in its early stages, several important early antiquity sites & societies have already been uncovered. These include the Ona sites near present-day Asmara and the ancient port city of Adulis, which dates back to the Puntite era and remained one of the primary ports in the Erythraean sea throughout antiquity. However, as I have discussed these polities in separate articles, this article will instead focus on four major sites located in Akele Guzay: Qohayto, Käskäse, Täḳwända & Addi Kramatən.

Some of these sites, particularly Käskäse, contain inscriptions mentioning the kings of DʿMT, suggesting they were part of the DʿMT kingdom. However, it’s likely that local lords (Sabaean: bʿl → baal) ruled the towns directly. Nevertheless, besides Qohayito, which shares the most affinity with Adulis, these sites generally display a cultural affinity with other DʿMT sites, as evidenced by similarities in pottery and religious artefacts, indicating they were part of the same broader cultural sphere during this period.

Qohayto/ቆሓይቶ

Qohayto roughly translates to “stony hill” in Saho1.

As most of the architecture found at Qohayto, such as the Temples/Churches & Palaces date to the first millennium AD, they are thus out of the scope of the article, therefore, this section will be relatively short. Another article will cover this later period.

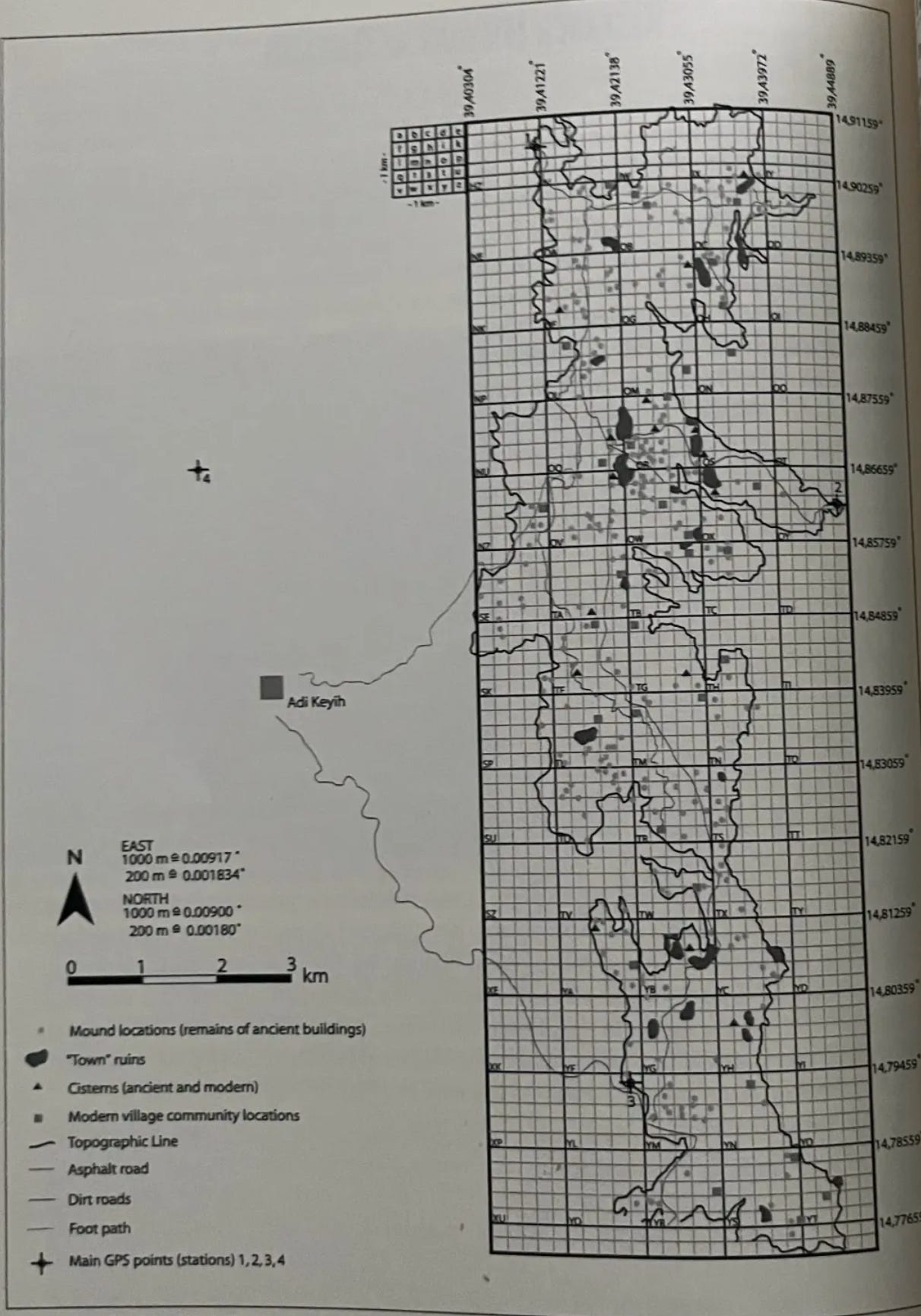

Qohayto is an archaeological site located northwest of the modern-day city of Adi Qeyeh in Eritrea, spanning approximately 32 square kilometres. The area was likely inhabited as early as the Neolithic period, as indicated by numerous cave paintings discovered near Qohayto2. However, it first experienced substantial growth during the first millennium BC. As the port city of Adulis to the north expanded because of increasing trade through the Red Sea, Qohayto also benefited. It was the closest town to Adulis, located in the highlands and thus the first stop for any merchants travelling from Adulis further into the interior, & the last stop for merchants before arriving at Adulis.

Many archaeologists and historians associate Qohayto with the ancient trading city of Koloe, mentioned in Greek sources like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea3. Some also propose that Qohayto served as a retreat for wealthy elites—particularly successful merchants from Adulis4, who built lavish residences there. This theory is supported by the presence of numerous elite structures, some located near scenic views.

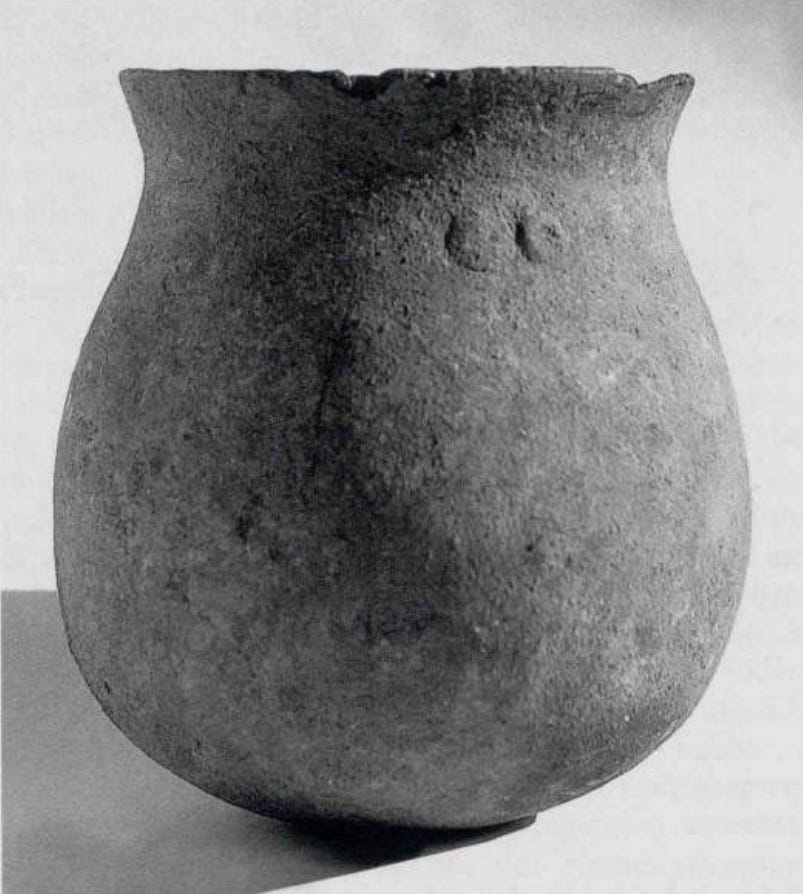

Qohayto is home to over 307 residential-style structures dating to the early antiquity period, at least 15 of which were large elite complexes, likely occupied by nobles, wealthy merchants, or skilled artisans5. Much of the site dates to the first half of the first millennium AD; however, evidence of occupation before this also exists, as structures/pottery dating to the first millennium BC have also been found, such as the pottery jar pictured above. Perhaps the most remarkable architectural feature from the early first millennium BC is the ancient dam, named Safira, after the nearby village inhabited by Asaorta Sahos.

Qohayto was comprised of dozens of settlements, the largest located east of the Safira Dam. In total more than 28 settlements were identified, with half classified as large towns or “city ruins”6.

Safira Dam

The Safira Dam was built using limestone and had a capacity of approximately 5,000 cubic metres of water, with a 67-meter-long and 3-meter-high wall blocking off the water7. Some archaeologists argue that it was not intended for irrigation, as the water levels were too low and fresh water was likely readily available nearby. As a result, it has been theorised that the structure may have rather served as a bathing pool, initially for pagan rituals, and possibly later for Christian practices such as baptisms. Another possibility might be that it was a cistern for local animals8.

Some suggest the dam is evidence that the Queen of Sheba once ruled in the Qohayto region, while others claim she once bathed in its waters.

Archaeologists have yet to reach a consensus on the date of the Safira Dam. Some suggest it may date to the early first millennium BC, coinciding with interactions with the Sabaeans to the east, while others propose a construction period in the first half of the first millennium AD. However, a study conducted in 1997 estimated the dam’s origin to be around 500 BC9.

Video showcasing The Safira Dam, Credit (2:36-2:52):

Täḳwända/ተዀንዳዕ

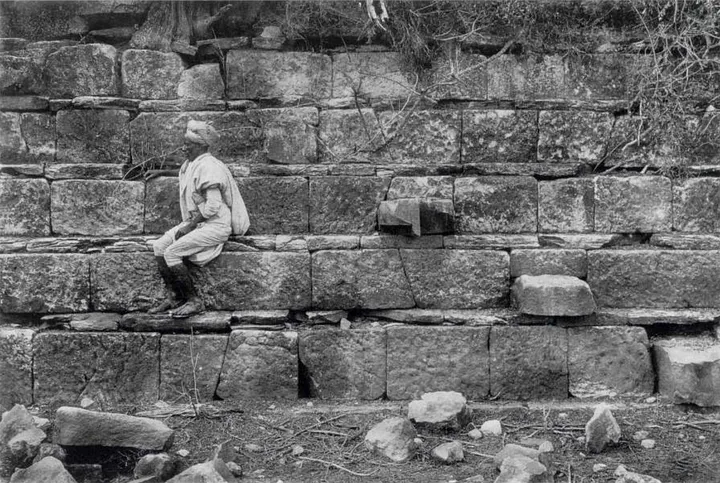

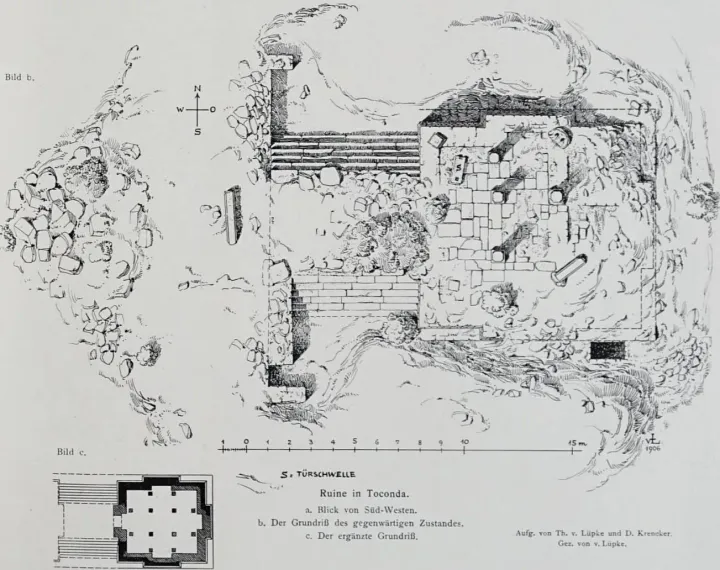

South of Qohaito, approximately 4 km south of the modern city of Addi Keyh, lies the archaeological site known as Täḳwända, which covers around 1 square kilometre10. Here, a carved stone fragment featuring a depiction of a snake was discovered. This stonework appears to have belonged to a nearby temple structure (categorised as Ruin I), which covered an area of around 90 square metres and was constructed entirely of stone.

The temple featured floors made of coloured marble and granite tiles, along with at least two rows of five columns. While the architectural style of the pillars might align with other stone buildings from the early first millennium AD, the depiction of snakes is highly unusual, particularly after the Christianisation of the region in the 4th century AD and shows no affinity to other archeological findings of that era11. This suggests that the temple possibly dates to a pre-Christian era, likely before the 4th century, however, archeologists are unsure of any precise dating.

In my view, the snake-like depiction represents Arwe, the serpent deity, suggesting the temple dates back to the early first millennium or even older.

The serpent god Arwe was one of the indigenous deities worshipped in the highlands of northern Eritrea & Ethiopia before Christianity, and its association with the region dates back to the time of Punt.

Käskäse/ኻስኻሰ

Käskäse roughly translates to “Your brain is weak” in Saho12.

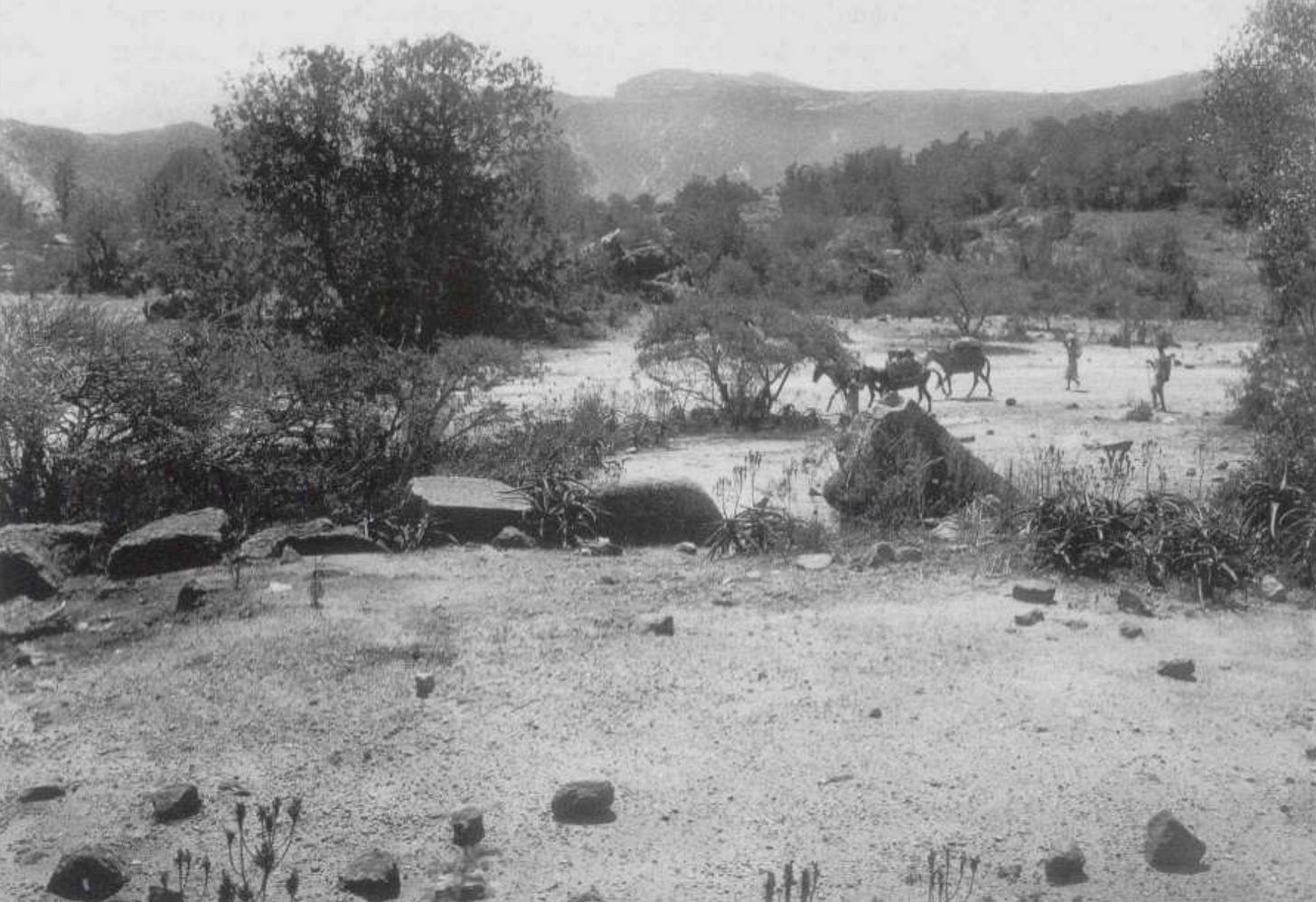

Käskäse is located approximately 5km north of the town of Senafe13. The archaeological site of Käskäse spans an area of 6.5 square kilometres14 (there’s much more that hasn’t been surveyed). The site is notable for its seven large monoliths/stelae.

To the south, four monoliths can be found. The first monolith, shown above, is shaped like a quadrangular prism and measures roughly 11 metres in length, 1.25 metres in width, and 0.905 metres in height15. No inscriptions have been found on it, and its significance remains unknown. However, archaeologist Dr Steffen Wenig observed a woman sitting astride (on either side, like when you ride a horse) the monolith, which may suggest some form of ceremonial use in the past16. At either end of the monolith, there is a circular depression, though the purpose of these features is also unclear.

– Source

A stela fragment, designated as RIÉ 12, was also discovered. Once part of a larger monument, the inscription mentions the ruler RDʾM, as discussed in the article on DʿMT. While it provides no further details, it was likely a commemorative or victory stela commissioned by the ruler, similar to others from the period.

Two other fragments of stelae were also found; these didn’t have inscriptions.

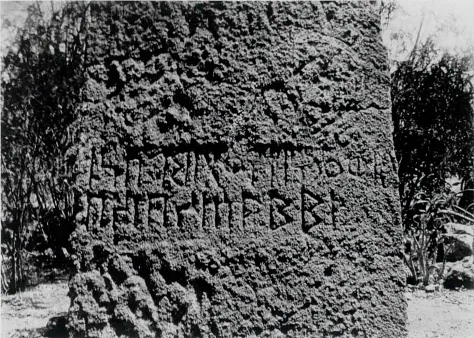

To the north, a few other stelae are present, one of which is a fragment measuring 82 cm by 77 cm at the base and 1.10 m in height. Scholars estimate that the original, unbroken stela once stood around 4.5 metres tall17. It bears an inscription previously discussed in the article on DʿMT, mentioning Wʿrn Ḥywt — one of the earliest known rulers of the DʿMT kingdom.

– Source

A tomb discovered on the western side of the site measured 1 metre in width and 1.5 metres in depth. Within it were human skeletal remains, a stone bead necklace, a large one-meter-long monolith, underneath which were over 100 bronze rings18.

Besides the stelae, various remnants of large architectural structures, such as stone blocks, have been discovered, often repurposed in later constructions like wells19.

Addi Kramatən/ኣዲ ክራማተን

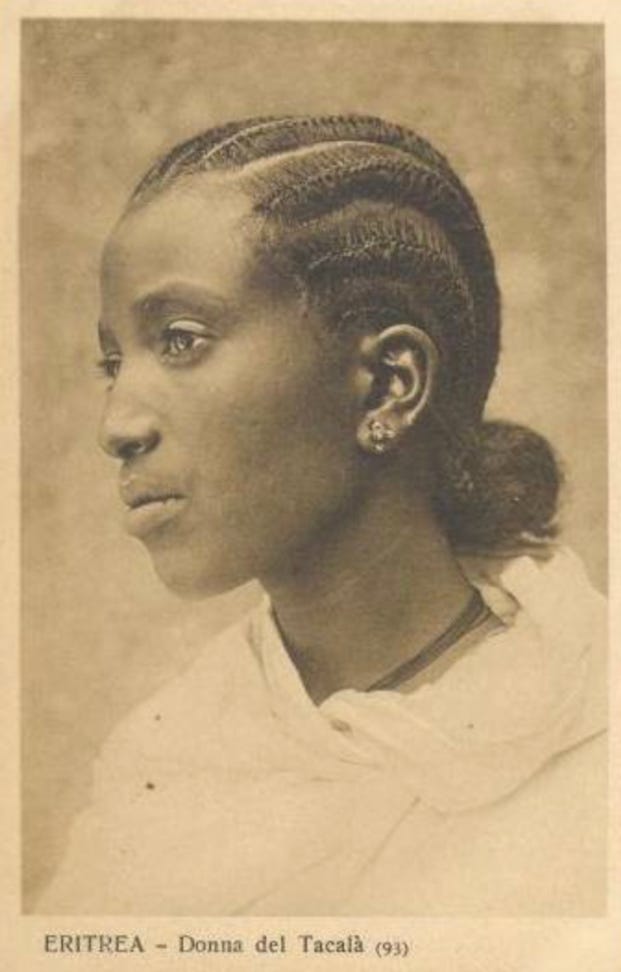

Sphinx-like statues such as the one above are not uncommon. Several similar examples have been discovered in the region, for instance, miniature sphinx-like figures were found at Senafe.

Situated to the west of Käskäse lies the archaeological site of Addi Kramatən, which dates back to around the first millennium BC20. The site is known for its sphinx‑like statue, measuring roughly 24 cm in height and 16.5 cm in width21.

The statue’s head is human, adorned with two necklaces, while its back legs resemble those of a lion. The hair is styled in plaits (ኣልባሶ/Albaso – a hairstyle still common among women today in the region), flowing into a lion’s mane along the back. Sabaic inscriptions on one of the surviving feet read “whbwd”22 (meaning unknown, but it might be the name of the creature/statue).

Scholars propose that this artifact may reflect Meroitic cultural influences23. Given the centuries‑long trade routes along the Nile (flowing from Egypt through Sudan and then finally into the tributaries located in Eritrea) it’s plausible that aspects of Egyptian and Meroitic culture gradually spread southward over time. For example the ONA site further north in Asmara is greatly influenced by societies of the Nile Valley24.

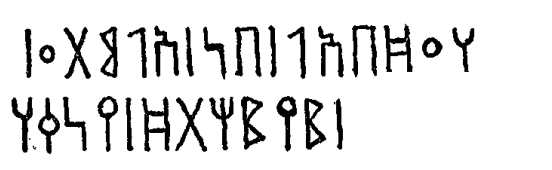

Also unearthed at the site was the altar on which the sphinx now stands. The altar measures approximately 59.7 cm long, 44.5 cm wide, and 40.6 cm high25. One side bears the following Sabaean inscription:

The inscription is translated as follows:

MR’HW possibly refers to the name of the sculptor who made the statue (the name might be vocalised as መርሃዊ →Merhawi →, which roughly translates to leaderly).

ḎT ḤMN refers to the goddess Dat Ḥimyam, a female Sabaean deity associated with the sun, fertility, and procreation rituals, who was venerated during the DʿMT period. Therefore, the sphinx might have represented Dat Ḥimyam.

Various Views Of The Sphinx & Altar – Source: The National Museum Of Eritrea

Archaeologists have also uncovered stone walls bonded with clay mortar near the statue26, thus this statue was likely housed in a temple, similar to those discovered at Yeha or Meqaber Ga’ewa.

Conclusion

To conclude, the four archaeological sites of Qohayto, Käskäse, Täḳwända, and Addi Kramatən in the Akkälä Guzay region represent some of the earliest known highland societies and are the start of history in the region (before this, other societies did exist, but no written language has been found, hence the designation pre-history). While sites like Käskäse declined after early antiquity, others—particularly Qohayto—grew in prominence, with several palaces constructed after the period covered in this article. Nevertheless, much remains undiscovered, as archaeological investigations have so far been limited to small areas & mostly conducted during the 20th century. As research expands in the future, it is likely that many more artefacts and sites will be uncovered in Akkälä Guzay and its surrounding regions, giving us a better understanding of these early societies.

- The Saho of Eritrea: Ethnic Identity and National Consciousness, pg 100. ↩︎

- The Archeology Of Ancient Eritrea, pg 298. ↩︎

- The Archeology Of Ancient Eritrea, pg 289-290. ↩︎

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica O-X, pg 295. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 366. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 364. ↩︎

- Duncanson, D. J. (1947). GIRMATEN—A NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE IN ERITREA (PLATEV III), pg 106. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 386,387. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 381. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 344. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 351. ↩︎

- The Saho of Eritrea: Ethnic Identity and National Consciousness, pg 100. ↩︎

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica He-N, pg 352. ↩︎

- “The Sabaen Man’s Burden” Questioning Dominant Historical Paradigm with New Archaeological Finding at Keskese Valley, pg 33. ↩︎

- “The Sabaen Man’s Burden” Questioning Dominant Historical Paradigm with New Archaeological Finding at Keskese Valley, pg 35. ↩︎

- Die Deutsche Aksum – Expedition 1906 unter Enno Littman (Vol.1), pg 331. ↩︎

- Recueil des inscriptions de l’Ethiopie des périodes pré-axoumite et axoumite, pg 81 ↩︎

- “The Sabaen Man’s Burden” Questioning Dominant Historical Paradigm with New Archaeological Finding at Keskese Valley, pg 32 & 33. ↩︎

- “The Sabaen Man’s Burden” Questioning Dominant Historical Paradigm with New Archaeological Finding at Keskese Valley, pg 35. ↩︎

- The Archeology Of Ancient Eritrea, pg 324. ↩︎

- Duncanson, D. J. (1947). GIRMATEN—A NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE IN ERITREA (PLATEV III), pg 106. ↩︎

- The Archeology Of Ancient Eritrea, pg 324. ↩︎

- The Archeology Of Ancient Eritrea, pg 324. ↩︎

- Urban precursors in the Horn: Early 1st-millennium BC communities in Eritrea, pg 850. ↩︎

- Duncanson, D. J. (1947). GIRMATEN—A NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE IN ERITREA (PLATEV III), pg 106. ↩︎

- Duncanson, D. J. (1947). GIRMATEN—A NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE IN ERITREA (PLATEV III), pg 159. ↩︎