The Aksumite Empire endured for nearly a millennium, amassing considerable wealth over the centuries. Some of this wealth was invested in the construction of grand and elaborate structures.

Introduction

Remnants of numerous large-scale Aksumite structures have been discovered across the Aksumite region. However, archaeological findings to date have been concentrated primarily near the two key city centres of Aksum and Adulis. These structures typically featured multiple floors and included dozens of rooms serving various functions, along with guard towers and courtyards. Historians believe these buildings were likely owned by extremely wealthy individuals, nobles, or royal families during the Aksumite period.

The following article explores several of these structures, distinguishing between those located in Aksum, Matara and Adulis. As always, archeological work in the region is in its infancy & much of the pre-existing work was completed in the 20th century AD.

Aksum

Dungur Palace/ “Queen Of Sheba’s Palace”

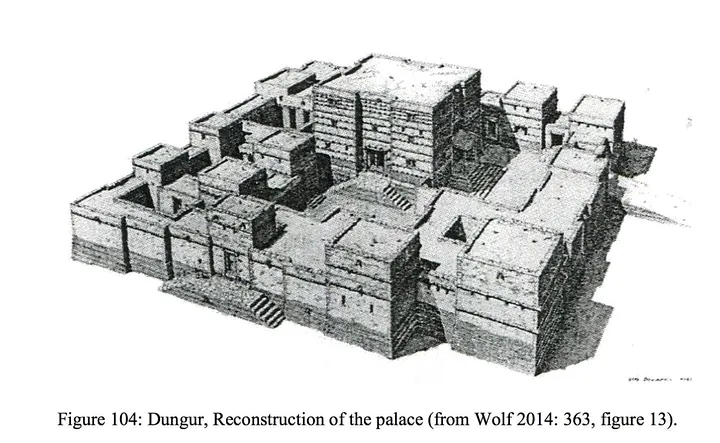

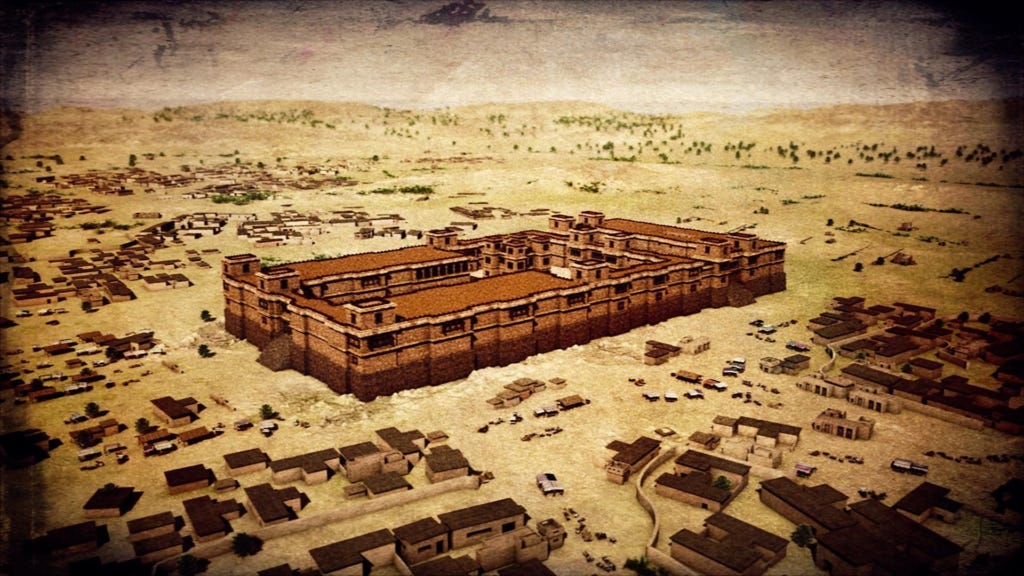

The Dungur Palace (sometimes referred to as “Queen Of Sheba’s Palace”), is situated slightly northwest of the current Aksum city centre, and dates to approximately the seventh century AD1 , it was likely used by a high official, noble or member of the royal family. It measures roughly 56 by 56 meters, thus having a total area exceeding three thousand square meters2. The structure is made mainly of large granite stones, adjoined with mud mortar. The main entrance lies on the east side of the palace with a double staircase, with additional entrances on the south and north sides. At the corners are watch towers, used to patrol the nearby surroundings.

This palace was excavated relatively recently, by a French archeologist mission, led by Francis Anfray between 1966-68.

The palace complex is surrounded by stone walls of a height of 5 metres3. The structure contained over 40 rooms, organised into four distinct clusters, each likely serving various purposes such as cooking, storage, and bathing4. At its heart was a central area with seven rooms, accessible by a grand staircase of seven steps from the east, west, and south. Surrounding the central building were walls standing three metres high, possibly built to protect the occupants and emphasise the importance of this section. Additional staircases in the northeast and southwest corners of the palace led to an upper storey5.

Numerous pottery items were also discovered around the structure, including cooking pots, bowls, and jugs. Notably, many amphorae—jars commonly used throughout the Mediterranean for storage—were found, along with some Egyptian cups. Most of the pottery artifacts date from the seventh and eighth centuries and Aksumite coins were also uncovered, including those from the reign of Emperor Armah, one of the last rulers of the seventh century6.

Below, is a great video showcasing what remains of Dungur Palace:

The Grand Palace Of Ta’akha Maryam

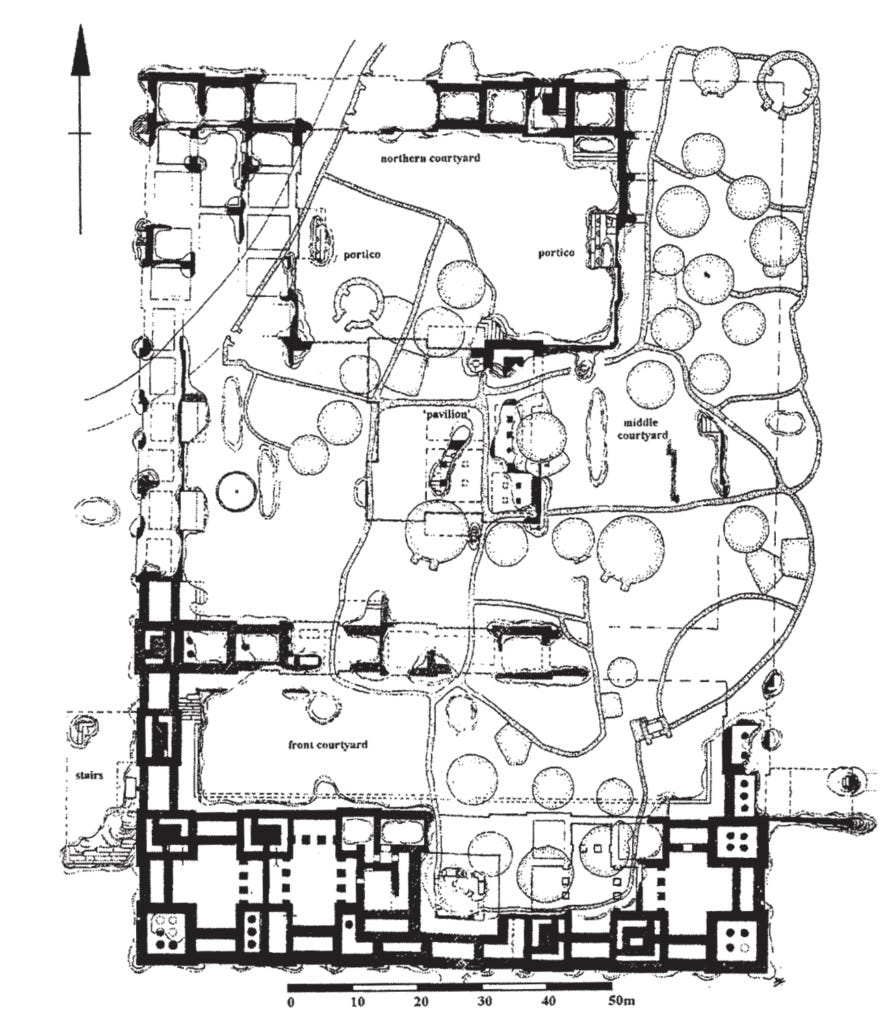

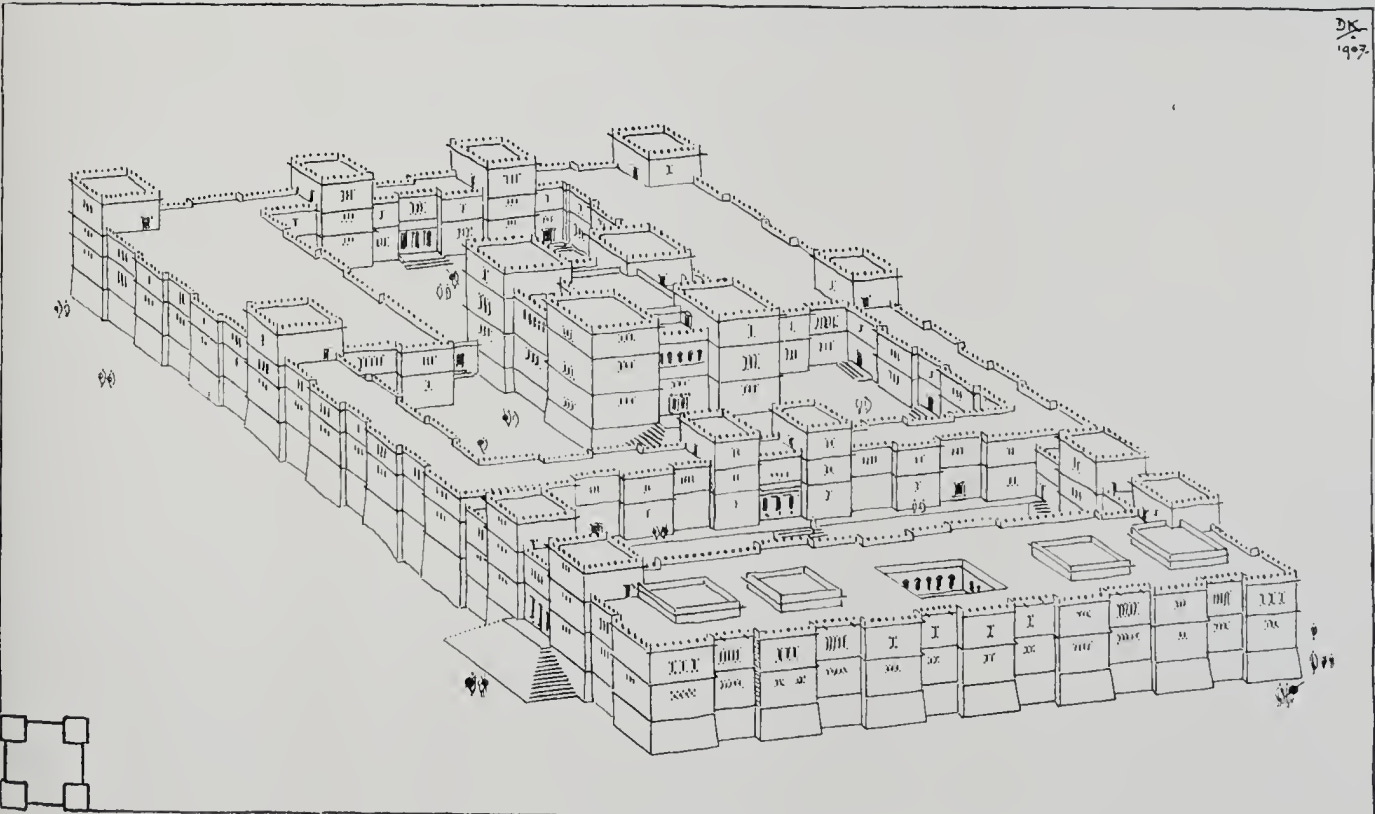

The Ta’akha Maryam palace complex in Aksum is the largest known Aksumite structure, measuring roughly 80 by 120 meters (around 10,000 square meteres)7. Featuring several dozens of rooms and multiple large courtyards. It was first unearthed by the German archeologist team led by Daniel Krencker in 1906. Unfortunately very little remains of the grand structure, with partial damage occurring during the colonial era with Italian road construction activities.

The largest courtyard, the North Courtyard, measured approximately 27.5 by 43 metres and was accessible from the northern side, connecting to various sections of the palace8. The most prominent entryway, however, was the grand western entrance, which featured a wide staircase leading to the Front Courtyard. Additional staircases on the eastern and southern sides provided alternative access points.

The Central Building, likely serving as the emperor’s or royal quarters, measured approximately 24 by 24 metres9. It was divided into two equal sections and included a large columned hall with 20 square columns, likely used for official gatherings or royal ceremonies. This hall was encircled by a continuous corridor leading to other rooms, which likely housed high-ranking officials and members of the royal family. Remnants of staircases throughout the building suggest it was a multi-storey structure.

The entire palace complex was built atop a 4-metre-high podium10, with its exterior stone walls reinforced by watchtowers at the corners for defensive purposes. Specialized rooms throughout the complex housed soldiers, and court officials, as well as several storage areas for food, military equipment and administrative tools.

The Castle Of Enda Mikael (House Of Michael) & Castle Of Enda Semon (House Of Semon)

At least two other significant palaces have been discovered, although information about these sites is limited due to a scarcity of archaeological remains and recent disturbances from construction projects, such as roadworks. One of these sites is Enda Mikael (House of Michael), an archaeological site dating back to the Aksumite period that revealed a palace structure measuring 27 meters by 27 meters, with a large eight-stepped staircase at the front entrance, measuring 4 meters in height111. The building was organized with a central courtyard surrounded by corner rooms and internal stair towers, which were likely used for access between multiple floors. The remains of pillars and stair towers also suggest a complex structure with multiple stories.

Local tradition states that a church dedicated to Saint Michael12 was once present in this location – this might hint at a dual religious role of the palace.

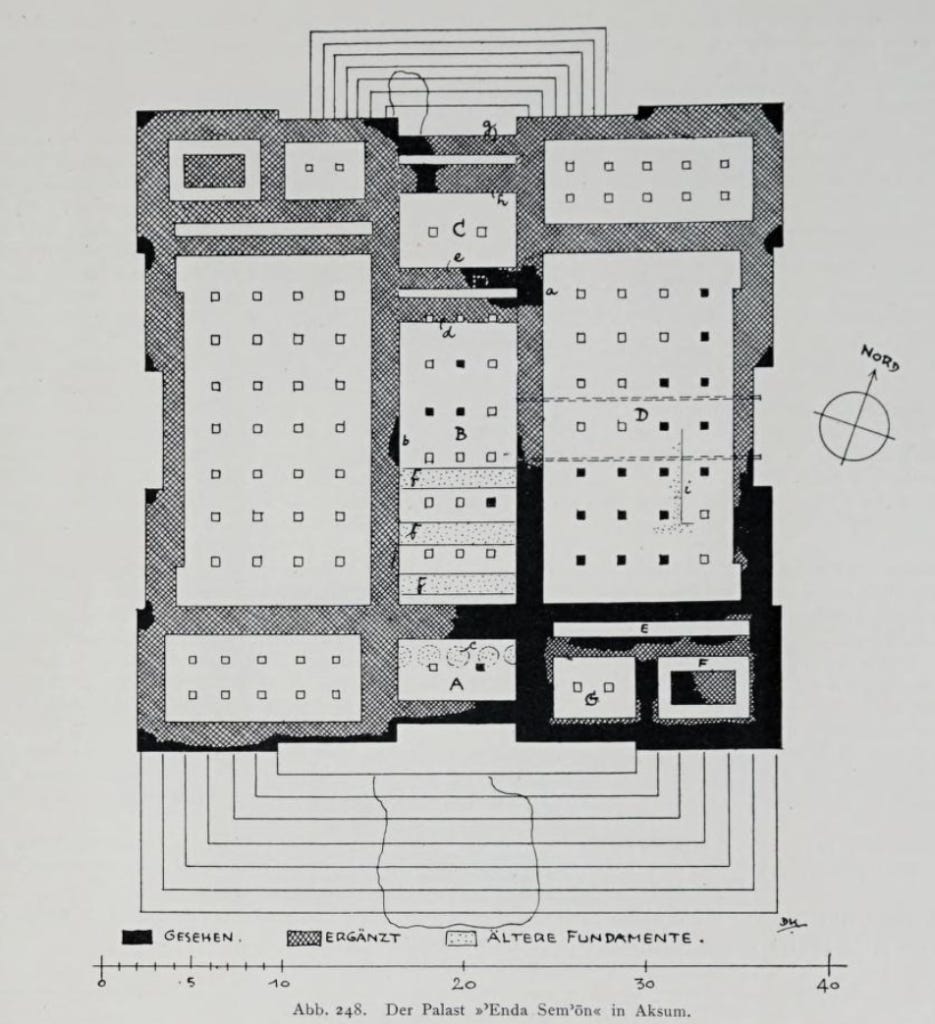

The Castle Of Enda Semon (House Of Semon)

Located 250 metres northeast of Enda Mikael lies another site, named Enda Semon, dated to the early 4th century AD13. Measuring 35 by 35 metres, the site features a five-stepped entrance on the southern side of the building. Excavations were hampered by modern overbuilding and poor preservation. The palace exhibits a clear square layout, similar to Enda Mikael, with staircases on both the southern and northern sections, thereby likely indicating a multi-storeyed building14.

Excavations were hampered by overbuilding during the medieval and pre-modern periods, thus leading to poor preservation and little remains in the present day. However, some information can be gleaned such as parts of the interior layout. The structure included a central columned hall flanked by entrance halls on the north and south (Room A and C), also a room for drainage (Room B) and a guard post (Room F)15.

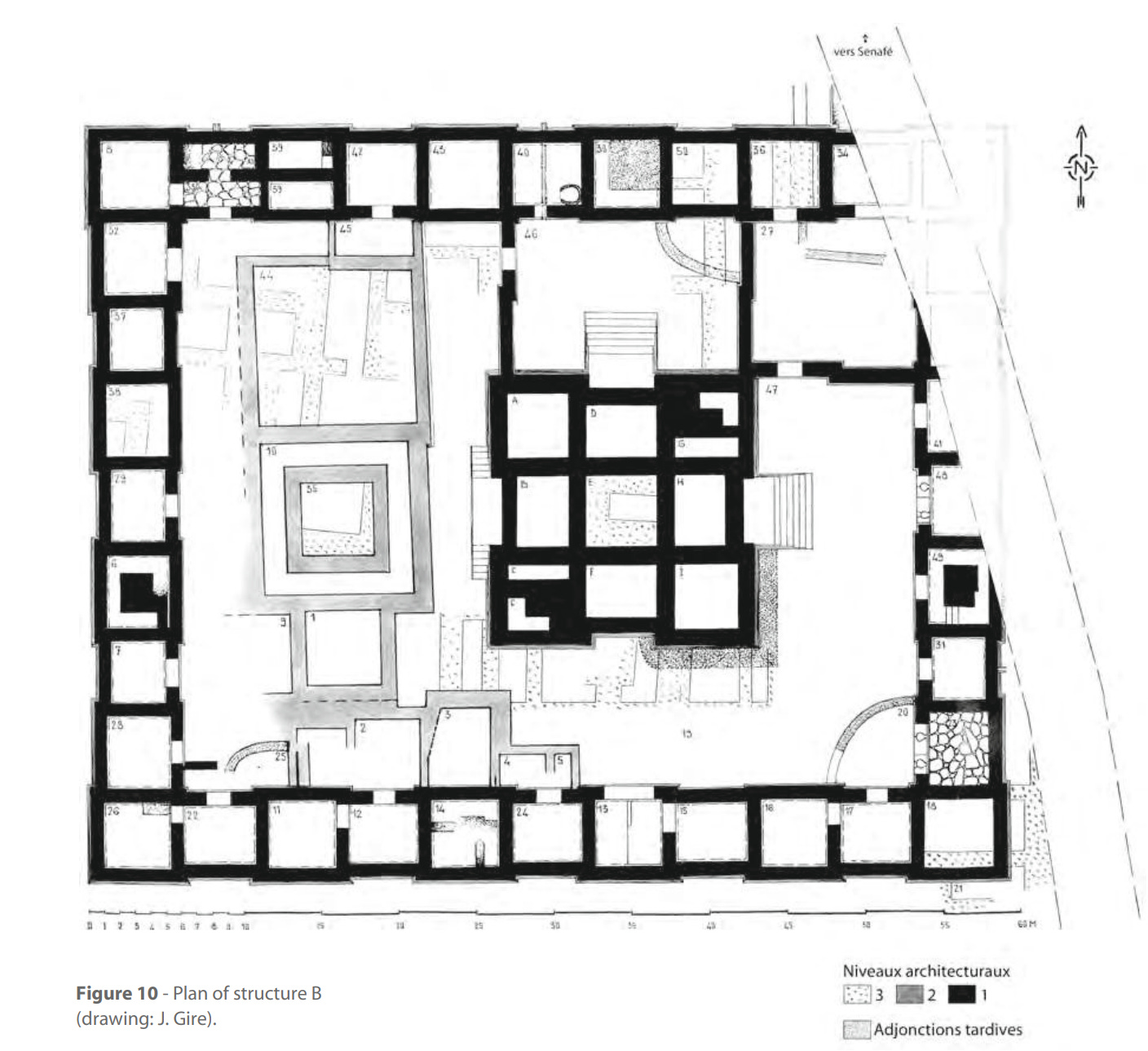

Matara

At Matara, several large structures, some of them palaces, dating to the Aksumite era have been discovered. These large complexes were primarily constructed from locally quarried stone and bonded with mud mortar. The largest palace, named “Structure B”, measured approximately 50 by 49 metres and featured 30 additional rooms distributed around the outer perimeter of the building. Inside, there were multiple courtyards, and at the centre stood a prominent structure measuring 17.5 by 17.5 metres. This central building was accessed via grand staircases on the north and east sides and contained several rooms.

Matara was once an independent city, which at one point warred with Emperor Kaleb, resulting in its eventual defeat16.

Another palace, referred to as “Structure C,” consisted of remnants of its central building, which measured 15.2 by 15.2 metres. Additionally, a 4th-century AD building, known as “Structure A,” was identified. Parts of its central structure were intact, measuring 12.6 by 11 metres, with a staircase located on the west side.

Adulis

Court-House

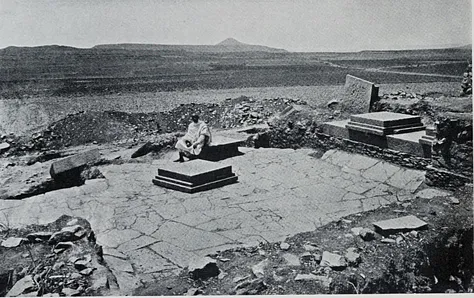

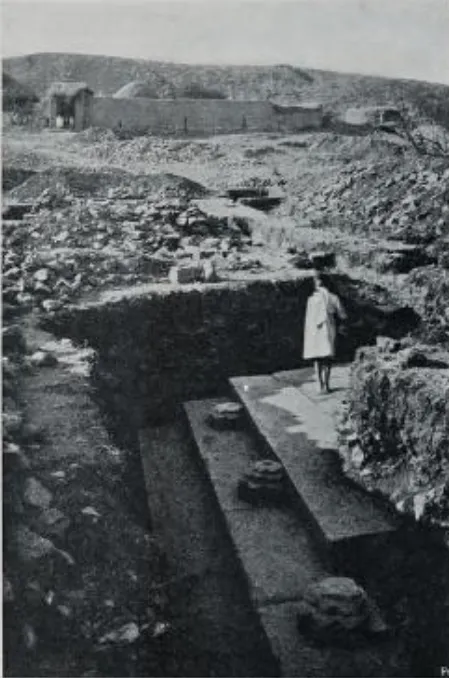

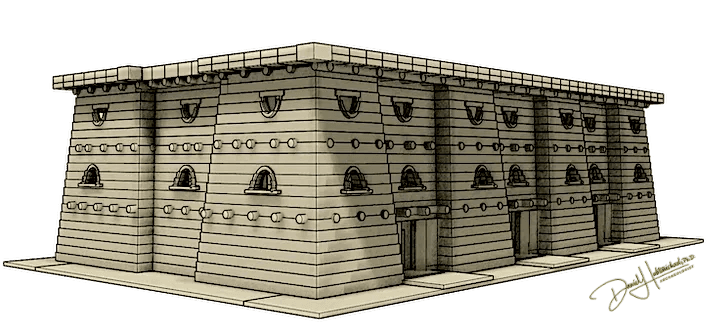

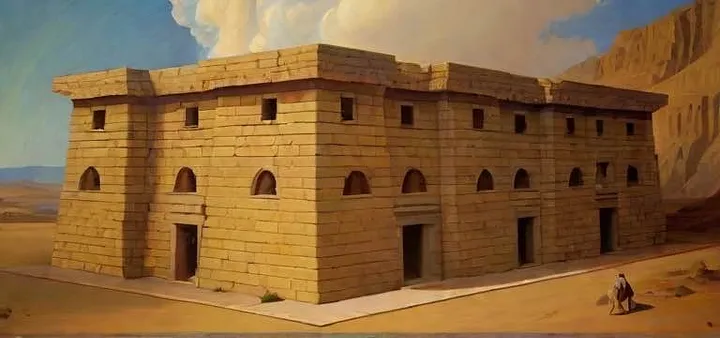

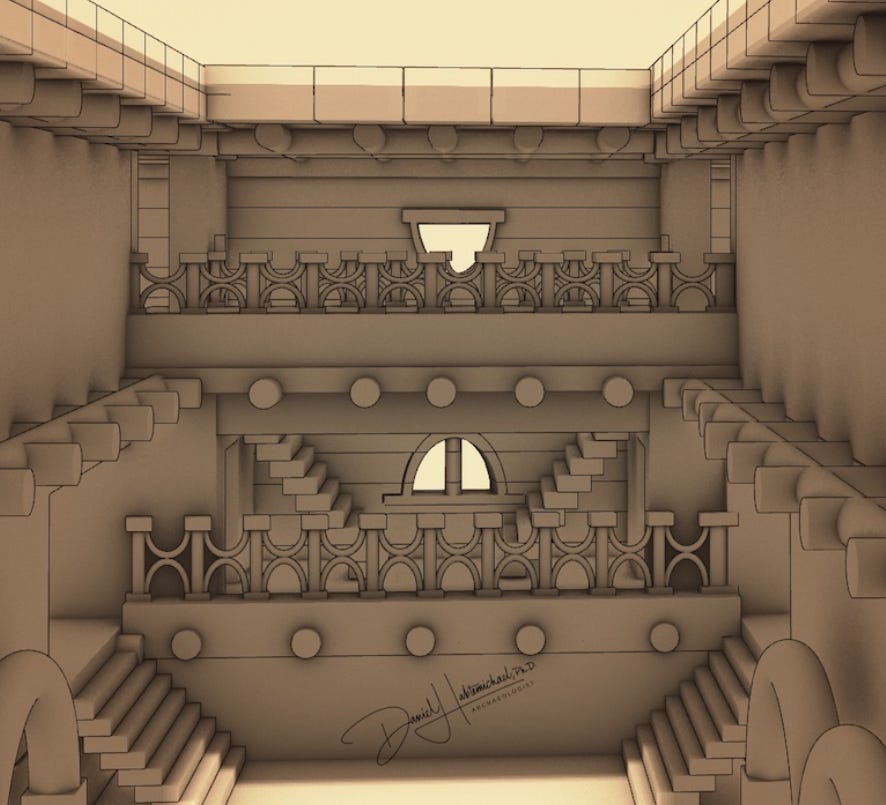

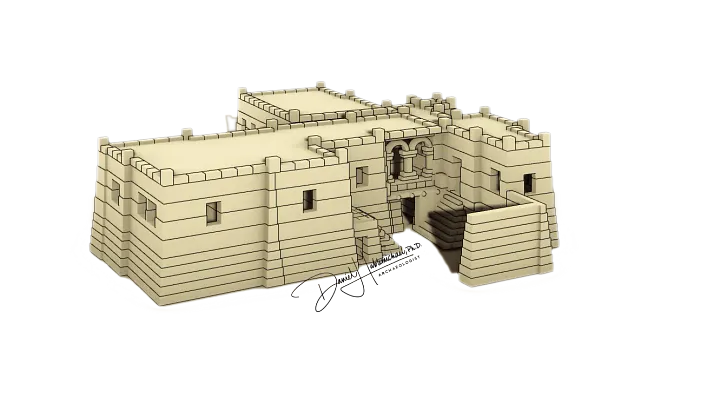

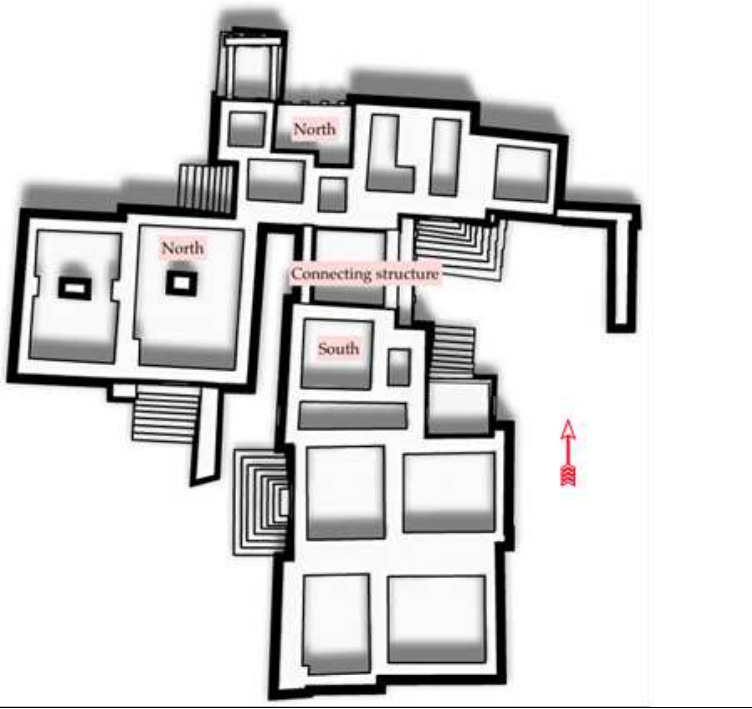

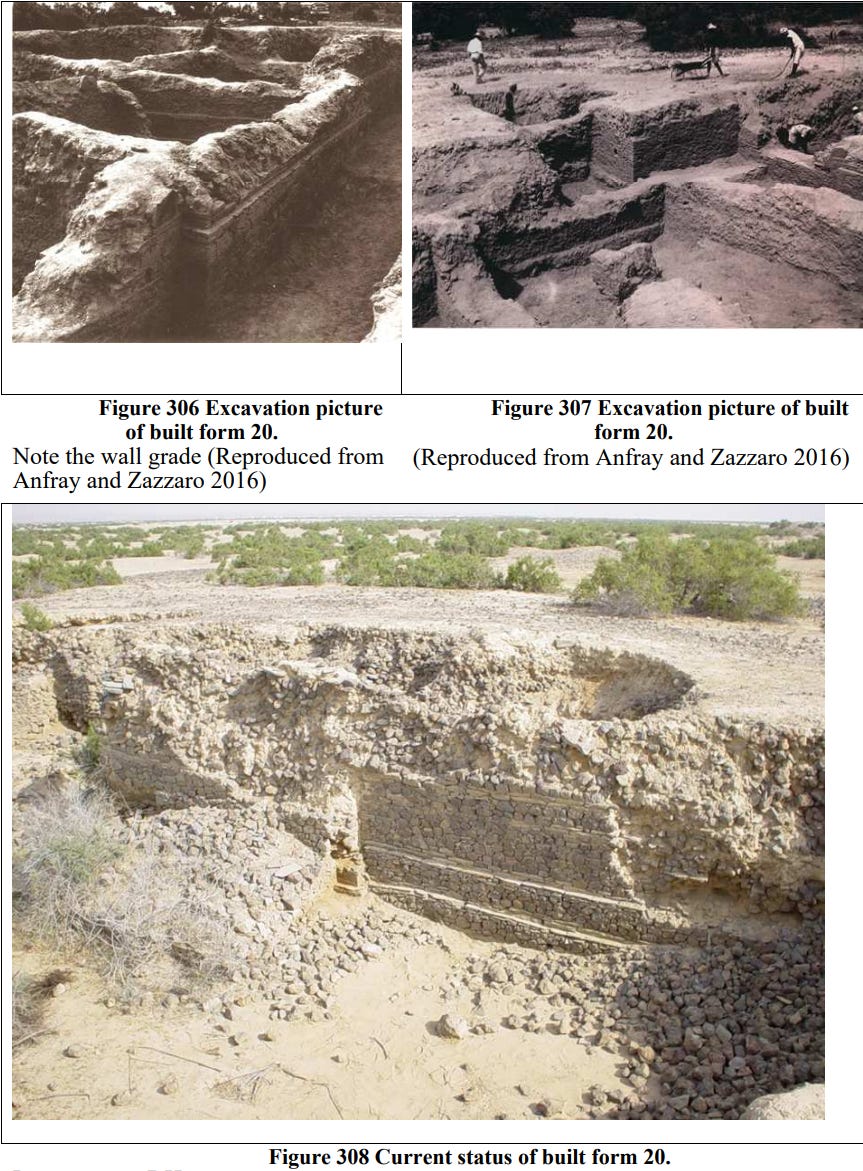

At Adulis, an ancient structure, first excavated in 1906 by Richard Sundström17, has been meticulously re-analysed by Dr. Daniel Habtemichael, who used these findings as a guide in creating a reconstruction. This three-storey building measured 38 metres in length and 22.5 metres in width, with an open area surrounded by 12 rooms – six on each side. Access to the upper floors was provided by a staircase on the western side, with each level containing 12 rooms18. The second and third floors likely housed political representatives from various regions around Adulis, while the central courtyard served as a venue for judicial hearings.

Kings Palace

This palace consisted of two interconnected buildings, one of which was constructed earlier, with subsequent additions and renovations over time. Altogether, the palace featured more than 14 rooms and multiple balconies19. It is believed to have served as the residence of a royal figure, possibly even the king of Adulis himself.

Dr. Daniel Habtemichael’s work is exceptional; I highly recommend visiting his website, where he provides detailed insights into various buildings at adulis and presents reconstructions of both their exterior and interior structures. https://www.adulites.com/TempleA/TempleA.php

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 65 ↩︎

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 63 ↩︎

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 63 ↩︎

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 63 ↩︎

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 64 ↩︎

- L’archéologie d’axoum en 1972, Francis Anfray, pg 64 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 112 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 112 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 112 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 113 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 108 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 107 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 112 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 111 ↩︎

- Ältere denkmäler Nordabessiniens, pg 112 ↩︎

- Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270-1972, pg 126 ↩︎

- Modelling the Local Political Economy of Adulis: 1000 BCE-700 ACE, page 386 ↩︎

- https://www.adulites.com/Court/court.php ↩︎

- https://www.adulites.com/KingResidence/Kingresidence.php ↩︎