Introduction

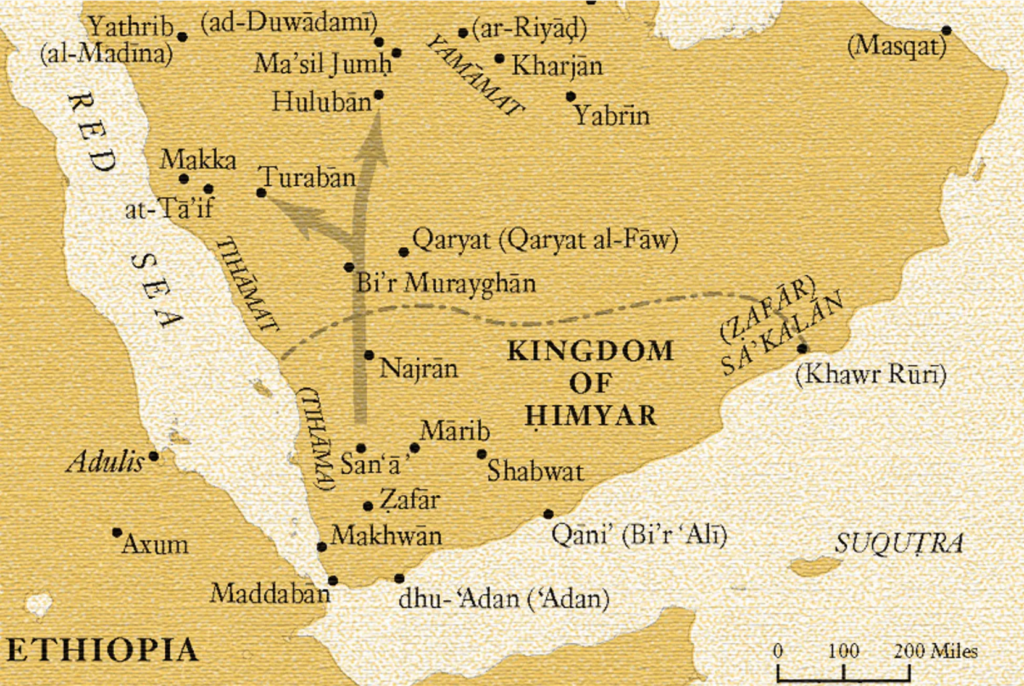

After securing his victories in South Arabia, Emperor Kaleb took significant steps to establish his influence in the region. He initiated the construction of churches around the Himyarite capital, Zafar. Before returning to Aksum, Kaleb crowned Sumuyafaʿ Ashwaʿ, a member of the Himyarite royal family—likely a prince—as the new King of Himyar1. This move not only ensured the legitimacy of Sumuyafaʿ Ashwa’s rule among the local population but also strengthened Kaleb’s control over the region. Sumuyafaʿ Ashwaʿ converted to Christianity and was baptized, further solidifying the Christian presence in Himyar. The following excerpt from the primary source named “Book Of The Himyarites” provides evidence of these events:

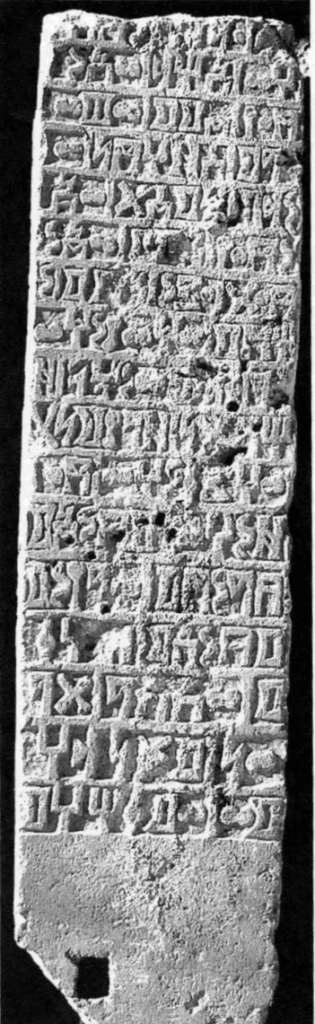

Ge’ez Inscription Found at Marib, also tells the same account2 (Note: The Inscription was found fragmented, with certain words missing…):

Abraha’s Origins

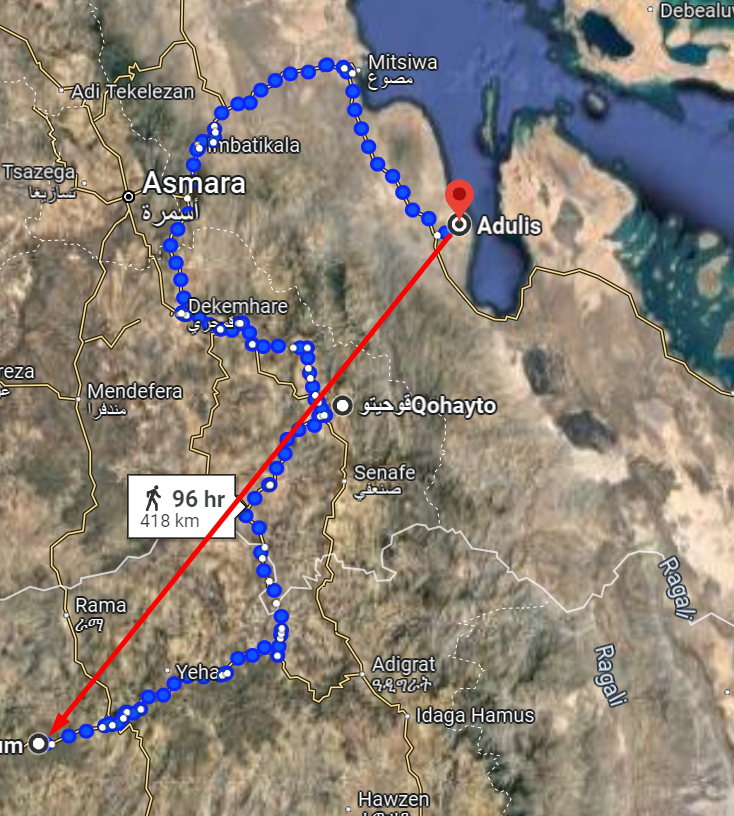

In addition to appointing Sumuyafaʿ Ashwaʿ as King of Himyar, Emperor Kaleb also entrusted General Abraha with a crucial role in the aftermath of the South Arabian campaign. Abraha, who hailed from humble beginnings in the port city of Adulis3, had risen through the ranks of the Aksumite Army due to his tactical brilliance and battlefield cunning. As noted by historian Sergew Hable Selassie, Abraha was neither physically imposing nor strong—described as short and stout, suggesting that his successes in battle were the result of his strategic acumen rather than personal combat prowess.

Although Abraha was not a general of the conventional Aksumite army during Emperor Kaleb’s invasion of Himyar—those positions were held by commanders like Hayyan and Ariat—he was entrusted with the leadership of a large contingent of slaves. With this unconventional force, Abraha played a pivotal role in the Aksumite victory in Himyar. His success earned him the position of commander over all Aksumite forces remaining in Himyar(around 5000), responsible for maintaining stability and ensuring the region’s tributary status to Aksum after Emperor Kaleb’s return.

He was crowned commander over all Aksumite forces by Emperor Kaleb at the capital of Himyar Zafar4.

The Greek Historian, Procopius mentions him as being a slave to a merchant operating in adulis, whether this is true is questionable as Procopius never visited Aksum directly and rather this information was told by third parties therefore it’s possible this information was tainted, in addition to this it wasn’t Aksumite tradition for generals to be from slave class5. however, there has to be some truth to it therefore it’s most likely at the very least he might have been from a poor background, that had once been part of the royal lineage but had since lost its grace. Interestingly the Indigenous Ge’ez version mentions his mother was a slave, maybe his father had married a low born….

Abraha’s Rebellion

Multiple sources attest to Abraha’s rebellion, including the Greek historian Procopius, as well as various Arabian accounts. However, the most detailed descriptions are provided by Arabian sources. Fortunately, Historian Sergew Hable Selassie translated and mentioned these sources in his book Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270, specifically on pages 145-146. The following accounts are from the above-mentioned pages…

Around 535AD, General Abraha with the support of the Aksumites forces stationed in Himyar, seized the royal court at Zafar and imprisoned Sumuyafaʿ Ashwa, Abraha now proclaimed himself King of Himyar. These events quickly spread around the realm, and it’s to no surprise that when Emperor Kaleb heard of this betrayal he was angered, therefore he sent over 3000 soldiers to pacify this rebellion and sent his royal prince Ariat to lead the army and take back power, Ariat6 was described as tall, striking general with battle-hardened experience, however soon after these forces arrived and had camped readying for battle, Emperor Abreha employed his messengers to be sent to the Camp with the following message:

The Duel

Prince Ariat likely viewed the impending confrontation with Abraha as a solemn and fateful moment. He understood that if a battle were to commence, it would pit two Aksumite forces against each other—composed of fellow Habesha brothers. There was no need for such bloodshed. Ariat believed that a duel between the two ambitious princes could resolve the matter of succession without unnecessary loss of life of their troops & civilians caught in the crossfire. Confident in his physical superiority, Ariat, who was taller and stronger than Abraha, felt assured of victory.

However, Abraha, who had risen from humble beginnings in Adulis and had a keen understanding of the darker sides of society, had other plans. Having climbed the Aksumite hierarchy through cunning and surrounded himself with a loyal force primarily made up of slaves and criminals, Abraha was no stranger to using trickery to achieve his goals. He devised a plan to secure his victory in the duel by deceit.

Abraha’s loyal servant, Arangada, hid in a trench near the secluded area where the duel was to take place, armed with spears. As the duel unfolded and it seemed that Abraha was losing, Arangada acted on his orders. He threw a spear aimed at Ariat’s head, but it deflected off Ariat’s helmet, grazing Abraha’s face instead. Undeterred, Arangada threw a second spear, this time striking Ariat mortally and killing him.

For his treacherous assistance, Arangada was promised any reward he desired. He made a degenerate request: to have premarital relations with any woman of his choosing, disregarding the women’s consent. This vile demand outraged the local populace, and Arangada was soon killed as a result.

Following Ariat’s death, his remaining forces, fearing retaliation from Emperor Kaleb for the dishonourable outcome of the duel, chose to remain in Himyar. When Emperor Kaleb learned of the slaying of Prince and General Ariat, he was enraged and demanded retribution. Knowing that his treachery would not go unpunished by Kaleb and fearing a stronger invasion, Abraha quickly sent messengers to Kaleb, offering his submission. The following is the message:

Abraha The King

After solidifying his control over Arabia, Abraha implemented strict laws, such as banning prostitution, with severe punishments for offenders, including the removal of tongues for those involved in procuring. He also forbade public singing and dancing7. Abraha further strengthened his rule by relocating the capital from the traditional Himyarite centre of Zafar to Sana’a. His reputation was enhanced by the restoration of the ancient Marib Dam, which had been in ruins for centuries. Additionally, he commissioned the construction of a grand church in Sana’a, which travellers later described as a magnificent structure reminiscent of Roman basilicas. Specifically, the church was described as per the following:

These laws were drafted with the assistance of Bishop Grigentius, therefore their overly zealous nature isn’t surprising.

The Pre-Islamic Importance of Mecca and the Brewing Conflict with Abraha

After successfully implementing various administrative measures, Abraha decided to host a diplomatic summit in 547 AD, with several of the greatest empires of the time. Ambassadors from the Eastern Roman Empire, the Shah of Persia, notable figures from South Arabia, and representatives from Abraha’s own emperor in the Aksumite Empire all gathered at Marib8. This event marked a significant moment in regional diplomacy, highlighting Abraha’s influence and his efforts to establish alliances and secure his position in the region.

Before the rise of Islam, Mecca was already a significant pilgrimage site, not for monotheistic worship, but for various pagan practices. The most notable deity worshipped in Mecca was Hubal, a prominent idol housed within the Kaaba, which was a revered structure even among the pagans. The Quraysh tribe, who were the custodians of Mecca, profited greatly from the influx of pilgrims who came to worship these idols. This pilgrimage not only brought religious prestige but also substantial economic benefits to the Quraysh, as pilgrims would spend money on accommodations, food, and gifts9.

In contrast, Abraha, a staunch Christian and the ruler of Yemen under the Aksumite Empire sought to spread Christianity throughout Arabia. He was also motivated by economic interests, as he desired to redirect the lucrative pilgrimage traffic to a grand church he had constructed in Sanaa, known as Al-Qalis. Abraha saw the pilgrimage to Mecca as both a religious and economic obstacle. Consequently, tensions between Abraha’s Christian forces and the pagan Quraysh of Mecca began to escalate, setting the stage for an inevitable conflict.

The primary trade route for goods passed through Mecca, extending to Damascus in Syria and then on to Rome and other regions10. This made Mecca a critical economic hub, which likely played a significant role in Abraha’s decision to invade, as controlling this vital route would have granted him substantial economic leverage over the region.

Abraha’s Invasions Of Arabia

After consolidating administrative control over Himyar, King Abraha led military expeditions in 552 AD into Hadramaut to the west,11 and several others into central Arabia, including regions such as Turaban & Haliban (The Later being part of the Ma’add Tribal Confederacy, around 300 km southwest of present-day Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)12, as-well-as north of Najran, reaching as far south as Mecca13. As a result, much of Arabia fell under King Abraha’s control.

The following is from a Ge’ez inscription found at Aksum, which attests to Abreha’s victories in Arabia:

Abraha’s Invasion of Mecca

The exact set of events behind Abraha’s invasion of Mecca in 552 AD, is debated among historians. Some accounts suggest that a man from the Hijaz region desecrated Abraha’s church in Sana’a, possibly by defiling it in an offensive manner14. This act, whether true or not, provided Abraha with a pretext, or casus belli, to march on Mecca. Arabic sources claim that Abraha assembled an army of approximately 60,000 soldiers, including a number of war elephants, and began his march towards Mecca. Along the way, he encountered and defeated various local tribes, such as those led by Dhu Nafr Al-Himyari, a local prince who resisted Abraha’s advance.

Islamic tradition dates Abraha’s attempted invasion of Mecca to 570 AD, While the exact date remains a point of contention, scholars have discovered an inscription attributed to Abraha that details his conquest of several Arabian tribes in 552 AD. These conquests spanned across Arabia, including the region near Medina, where one of the tribes pledged allegiance to him. According to Fisher Greg, author of Arabs and Empires Before Islam, it is very likely that Abraha led an expedition against Mecca, during which he ultimately suffered a defeat15.

As Abraha’s forces approached Mecca, they pillaged the surrounding countryside, causing significant losses for the Quraysh. Among those affected was Abdul Al-Muttalib, the grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad, who lost a large number of livestock to Abraha’s forces. This led to a notable encounter between Abdul Al-Muttalib and Abraha. According to the historian Sergew Hable Selassie, Abdul Al-Muttalib, representing the Quraysh, met with Abraha to discuss the return of his livestock. The Conversation is as follows:

Interestingly, Abdul Al-Muttalib did not ask Abraha to spare Mecca or the Kaaba; instead, he focused solely on recovering his animals. This interaction hints at the Quraysh’s confidence that the Kaaba, being sacred and under divine protection, would not fall to Abraha’s army.

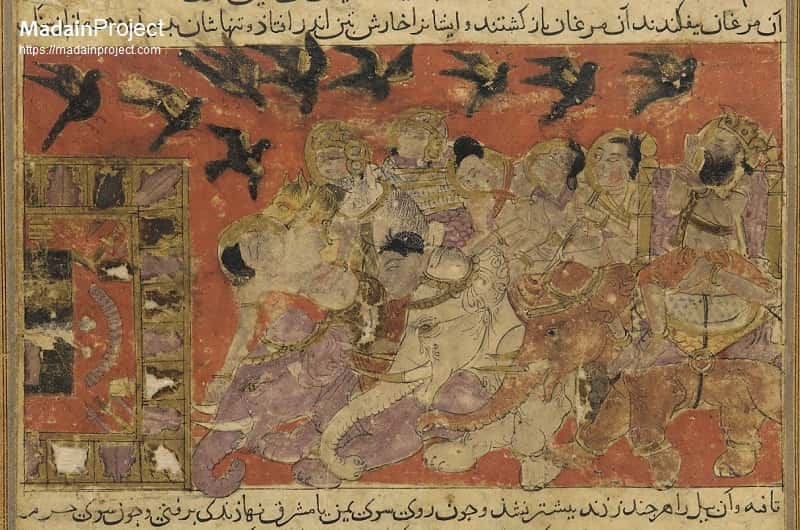

According to Islamic tradition, as Abraha’s forces prepared to attack Mecca, a miraculous event occurred. The Quran (Surah Al-Fil) describes how a flock of birds, known as “Ababil,” appeared and dropped stones upon Abraha’s army, decimating it. Additionally, the elephants refused to march towards Mecca, further hindering the invasion.

While Islamic tradition holds that this divine intervention was the primary reason for Abraha’s failure, some historical accounts suggest that a widespread outbreak of smallpox or another disease may have played a significant role in decimating Abraha’s army16. Regardless of the exact cause, Abraha’s campaign ended in failure, and he was forced to retreat back to Himyar.

Around 540AD, the Plague of Justinian began to take root across the known world, it’s very likely that this plague played a huge part in whatever battle that occurred at Mecca….

The Decline of Abraha’s Dynasty

After his unsuccessful campaign against Mecca, Abraha returned to Himyar, where he continued to rule until his death around 565 AD17. Upon his death, his son Yaksum succeeded him. Yaksum ruled for a few years, but his reign was marked by growing discontent among his subjects. The resentment in the kingdom grew to the point that, after Yaksum’s death, his brother Masruq inherited a troubled realm (Around 568-569AD)18.

Masruq proved to be an ineffective ruler, and his reign only exacerbated the dissatisfaction among the people of Himyar. This unrest prompted Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan, a prince with maternal ties to the old Himyarite royal family, to seek external assistance to overthrow Masruq. Initially, Sayf appealed to the Byzantine Emperor, but his request was denied. Undeterred, Sayf travelled to the court of the Sassanian Emperor, Khosrow I, where he presented his case in person19.

Sayf’s plea to Khosrow I is an important episode, as it symbolizes the shifting power dynamics in the region. The outcome was that Khosrow agreed to support Sayf in his bid to overthrow Masruq, which marked a significant turning point in the history of Southern Arabia. The conversation went as follows:

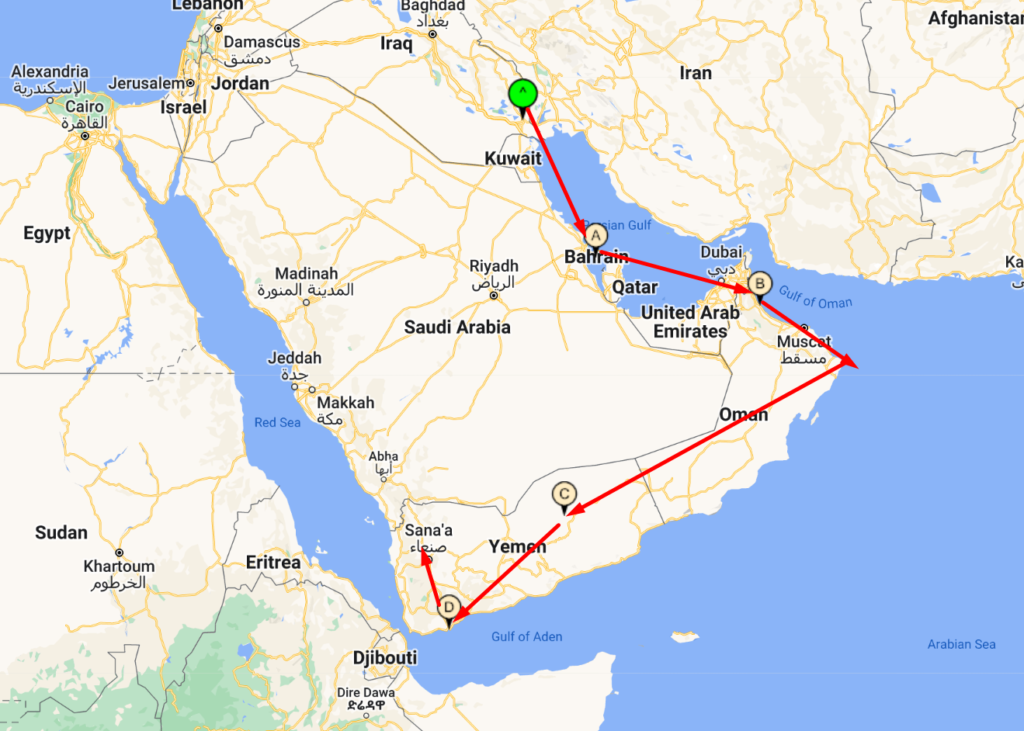

The Persian Intervention in Yemen and the Downfall of the Aksumite Rule

The Sassanian Shah, Khosrow I, was initially reluctant to involve himself in the internal affairs of Arabia by aiding Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan in his rebellion against the Aksumite rulers of Yemen. However, Sayf’s promises of immense treasures and the strategic advantage of influencing in Arabia ultimately swayed the Shah. Around 570AD, Khosrow dispatched a contingent of around 16,000 men, however around 4,000 died crossing the Persian Gulf20. They were led by the retired Persian general Wahriz. Some of this force was composed of imprisoned criminals, with nothing to lose21.

In 562 AD, Emperor Justinian of the Roman Empire negotiated a 50-year peace treaty with Shah Khosrow I22. This agreement likely allowed the Shah to redirect his economic and military focus towards the events unfolding in southern Arabia. In fact, this situation can be seen as a proxy conflict between the Romans and the Persians, for influence in this vital region.

Upon his return to Yemen, Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan began rallying the local Yemeni Arabs to his cause, eager to overthrow the oppressive Aksumite rule and reclaim their homeland. His efforts quickly gained widespread support. Meanwhile, Masruq, the beleaguered Aksumite king, became aware of the growing rebellion and hastily assembled an army of 100,000 men to suppress the uprising23. In response, General Wahraz and his fleet departed from Obolla (Modern Day Al-Ubulla, in Iraq) , and led his forces to capture Bahrain, then moved on to Sohar, the capital of Oman, where 4,000 men were stationed to quell any potential revolts against Persian rule. After securing Oman, Wahraz advanced into Hadhramaut24. Finally, his fleet landed at the port of Aden in Himyar, where they joined forces with Sayf’s rebels, readying themselves to confront Masruq’s Aksumite forces.

The Decisive Battle and the Death of Masruq

The ensuing battle between the Persian-Yemeni forces and Masruq’s Aksumite army was a turning point in the history of Yemen. Despite the numerical superiority of the Aksumites, the experience and cunning of General Wahriz played a crucial role in the battle’s outcome. Wahriz, who had a keen eye for battlefield opportunities, noticed that Masruq wore a distinctive and prominent ruby, which shone brightly and made him an obvious target. With a single well-aimed arrow, Wahriz struck Masruq in the head, killing him instantly and shattering the ruby into pieces25.

This is per Arabian sources, translated by Sergew Hable Selassie.

The death of their king demoralized the Aksumite forces, leading to their complete collapse. The loss of leadership and the psychological blow of seeing their king fall so suddenly and decisively caused the Aksumite soldiers to flee in disarray. With this victory, Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan and his Persian allies were able to overrun and conquer the entirety of Himyar. In the aftermath, many Aksumites were massacred, and the Persian-Yemeni forces solidified their control over the region.

The Betrayal and Assassination of Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan

Despite his victory, Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan’s reign was short-lived. Among the surviving Aksumites, a group of young boys had been spared and raised as Sayf’s personal bodyguards. Over time, these boys, who grew up wielding long spear-like weapons, earned Sayf’s trust and became integral to his protection26. However, this trust would prove to be fatal.

One day, while out hunting, Sayf found himself alone with these bodyguards. Seizing the opportunity, the Aksumite boys turned on him, killing him and thus becoming kingslayers. The leader of these assassins, the eldest among them, declared himself Governor of Yemen and took the name Abraha II27. This sudden and unexpected coup plunged Yemen back into turmoil.

The Final Persian Intervention and the End of Aksumite Influence

When news of Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan’s assassination and the subsequent Aksumite resurgence reached the Persian court, Khosrow I reacted swiftly. He ordered General Wahriz to lead a much larger force of 4,000 Persian soldiers back to Yemen to quash the rebellion once and for all. Wahriz, now an older but still formidable commander, marched south once more and decisively defeated the Aksumite forces. In the aftermath of this victory, the Persians carried out a brutal purge, massacring all remaining Aksumites, including those of mixed Aksumite-Arab descent, to ensure there would be no future uprisings28.

With the Aksumite presence in Yemen utterly eradicated, General Wahriz was appointed as the ruler of Yemen. Under his leadership, Yemen became a vassal state of the Sassanian Empire, paying tribute to Persia and effectively ending any Aksumite control in South Arabia29.

When Saif Dhu Yazan’s son saw the Persian force arrive at Aden with his army of ~8,000 Persians, he said the following to his father Saif:

Emperor Kaleb And The Roman Delegations

Emperor Kaleb Meets Ambassador Julianus

Meanwhile, as all this was developing in Southern Arabia, in Aksumite territory proper (In Africa), following his successful campaigns in South Arabia, Emperor Kaleb returned to Aksum around 526AD. Some years later, Emperor Justinian of the Roman Empire sent an envoy to Kaleb, proposing an alliance for a joint invasion of Persia. The Persians had imposed burdensome taxes on trade with India & lands beyond such as China, particularly on silk, which greatly concerned the Romans30. This envoy’s name was Julianus, and he also proposed to Emperor Kaleb that Abraha be tasked with Invading Persia by first Invading Central and Northern Arabia. Although Kaleb initially agreed to the alliance, he ultimately decided against the invasion, recognizing the significant risk of jeopardizing Aksum’s vital trade routes with the East, especially India. The economic consequences of such a conflict were deemed too severe, especially considering the fact an invasion of Persia, one of the four strongest empires of the time, wasn’t a task that could easily be accomplished, rather it would likely not be successful and would result in a great number of economic and social problems.

The following is a retelling of Ambassador Julianus’s mission to Emperor Kaleb.

Interestingly the Aksumites mentioned to the ambassador the difficulty of crossing the Arabian desert posed to any attempt of invading Persia.

Although Kaleb initially agreed to the alliance, he ultimately decided against the invasion, recognizing the significant risk of jeopardizing Aksum’s vital trade routes with the East, especially India. The economic consequences of such a conflict were deemed too severe.

Emperor Kaleb Meets Ambassador Nonnosus

In 530 AD31, a second delegation was sent by Emperor Justinian, led by the ambassador Nonnosus, to meet Emperor Kaleb. Notably, during his journey, Nonnosus provided a detailed account of the climate and wildlife in the region. He mentioned a place called Ave, likely referring to Qohaito or Matara, both of which are situated roughly midway between Adulis and Aksum and were known to the Greco-Romans. According to his observations, the climate from Qohaito to Adulis was hotter and more arid from late June to late September, while the route from Qohaito to Aksum experienced its wet season during this period. The opposite occurred from late December to late March. Additionally, Nonnosus reported seeing a large number of elephants halfway between Adulis and Aksum, near Qohaito. This observation aligns with our earlier discussions about the Aksumite period, when the climate was much greener and more conducive to wildlife, including elephants. Elephants were a significant element of trade during both Puntite and Aksumite times.

Search up the climate in the highlands of Eritrea vs Aksum, and you will still find that what Nonnosus described is still true, nearly 1500 years later.

Resources Used:

Please Click Here To View Available Links To Books Used (Forum page) -> If you have any suggestions/corrections to the article, please also post them on the forum.

Bibliography

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 87 ↩︎

- Arabs And Empires Before Islam, pg 164 ↩︎

- The Throne Of Adulis, pg 111 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 135 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270 135 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 87 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 146 & 147 ↩︎

- Arabs And Empires Before Islam, pg 150 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 150 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 147 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 147 ↩︎

- Arabs And Empires Before Islam, pg 151 ↩︎

- The Throne Of Adulis, pg 115 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 151 ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 152 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 152 ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 152 ↩︎

- Arabs and Empires Before Islam, pg 152 ↩︎

- The Throne Of Adulis, pg 117 ↩︎

- The countries and tribes of the Persian Gulf, pg 26 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 154 ↩︎

- The countries and tribes of the Persian Gulf, pg 25 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 155 ↩︎

- The countries and tribes of the Persian Gulf, pg 26 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 155 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 156 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 156 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 156 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 156 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 17 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis, pg 109 ↩︎