Encompassing the time period from around 1000-400BC.

Introduction

From the first millennium BC onwards, the groundwork for the future Aksumite Empire began to take shape. In the highlands of northern Ethiopia (in northern Tigray) and southern Eritrea (Debub region), agropastoral communities emerged. These communities established permanent settlements, ranging from hamlets to villages built from stone. The people cultivated crops such as teff and domesticated animals like cattle1. In addition to preparing meat and lentil stews, which were cooked and preserved in ceramic vessels of varying sizes and served with ceramic spoons, they also made breads from wheat and barley, such as Brkuta and Kicha.

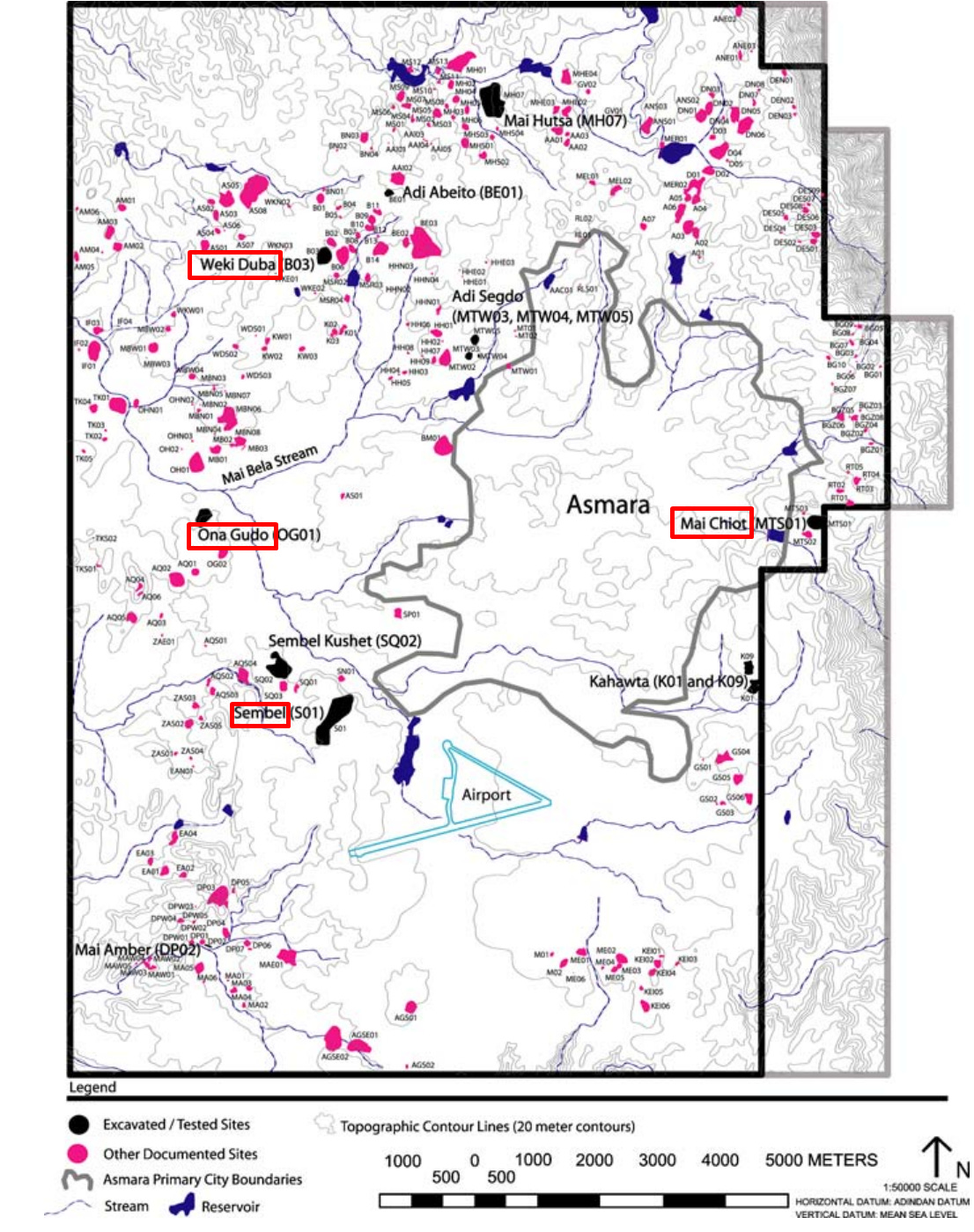

In the 1960s, the exploration of the Asmara Plateau in Eritrea was initiated by Italian archaeologists V. Franchini and G. Tringali, who introduced the concept of ‘Ona sites’ or ‘Ona Culture’. Their pioneering work was documented in Italian scholarly publications. Subsequent archaeological investigations into these Ona sites have been led by Peter R. Schmidt, Matthew C. Curtis, and Zelakem Teka.

At these Ona sites, multiple artifacts dated to 800BC to 400BC were found. Specifically, I’ll discuss some of the following sites here: Sembel, Mai Hutsa, Mai Chot and Weki Duba.

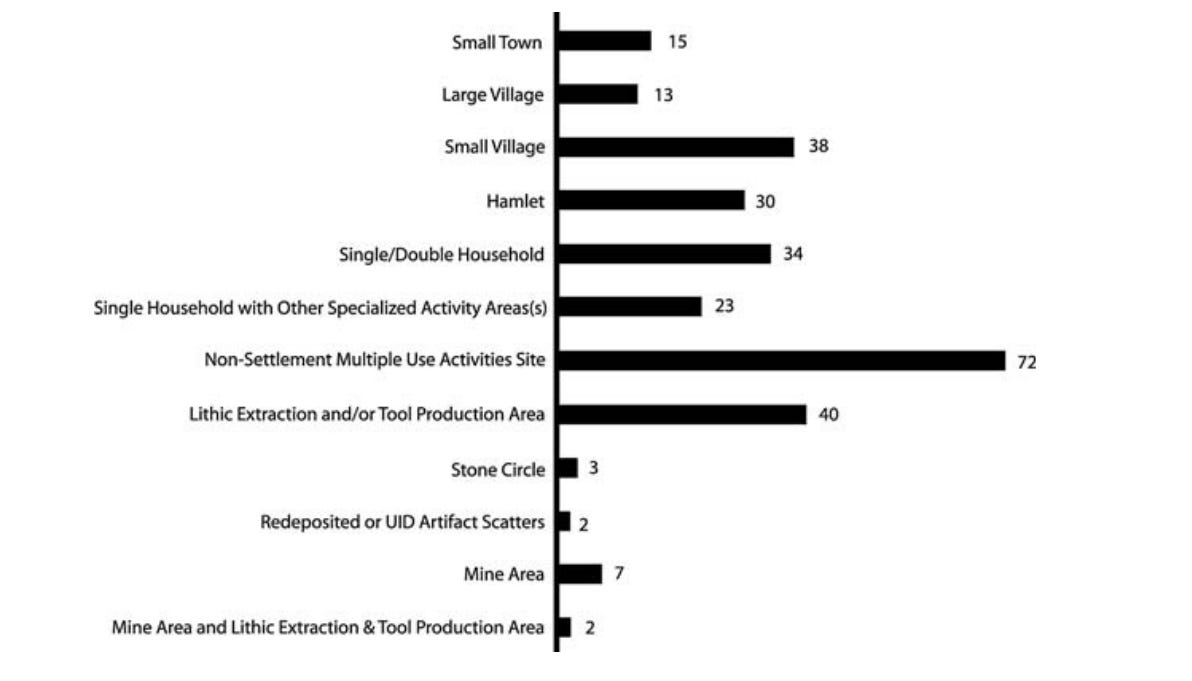

Research indicates that many of the sites were established by individuals already versed in agriculture and animal husbandry. Notably, the lack of external fortifications around the villages or hamlets, combined with the absence of artifacts exclusively associated with an elite class, suggests a strong likelihood of a more communal, non-hierarchical society2.

Ona/ዑና is a term in the Tigrinya language that describes ruins or old houses/villages where populations once resided.

Sembel

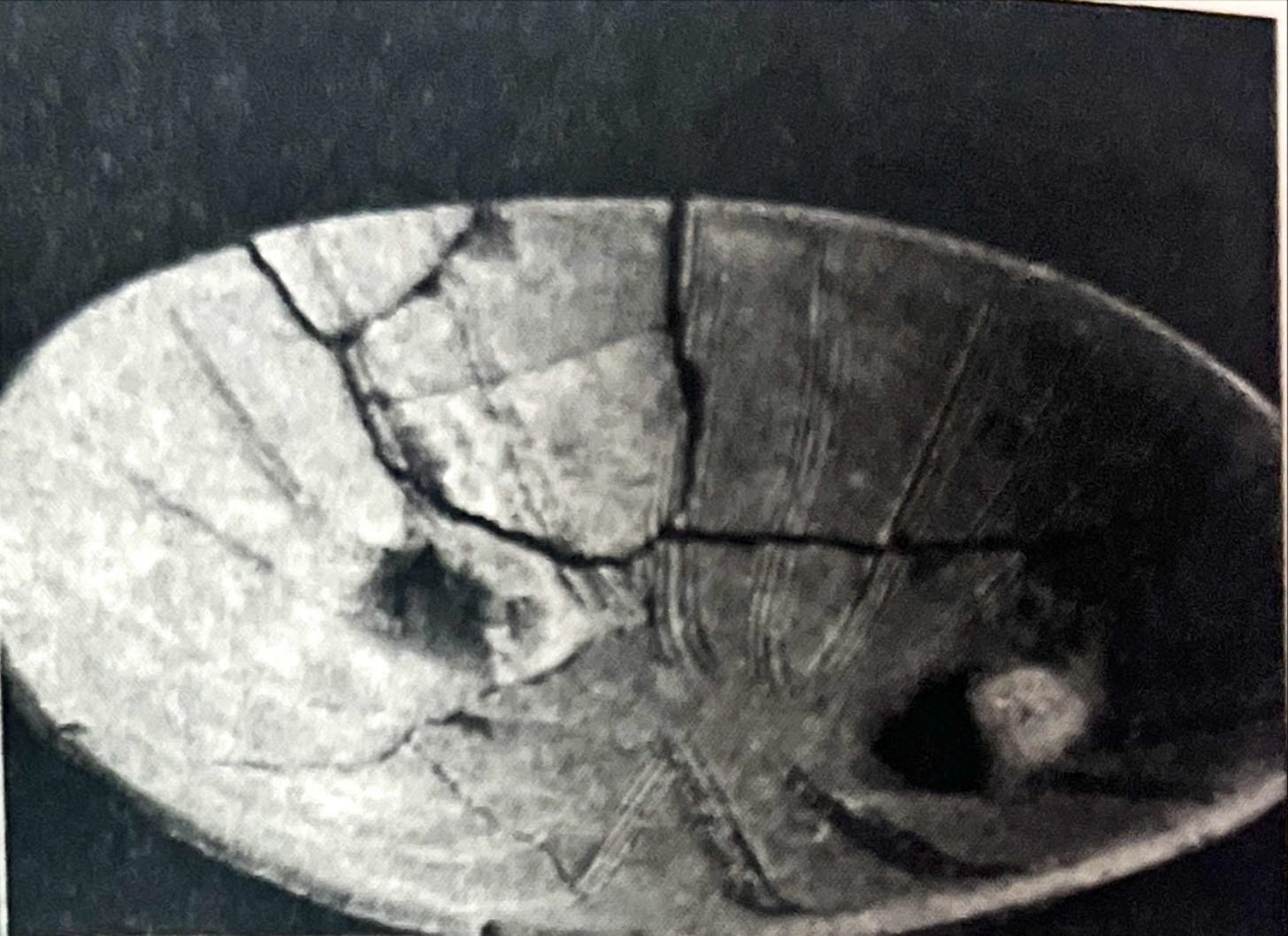

Covering around 12 to 13 hectares, the Sembel site underwent radiocarbon dating across various sections, establishing its primary occupation from 900 BC to 400 BC3. Excavation efforts revealed numerous small bowls and cups, each measuring approximately 5 cm in diameter (referred to as Tina Cups). These cups could have been used for drinking water or storing butter/ghee.

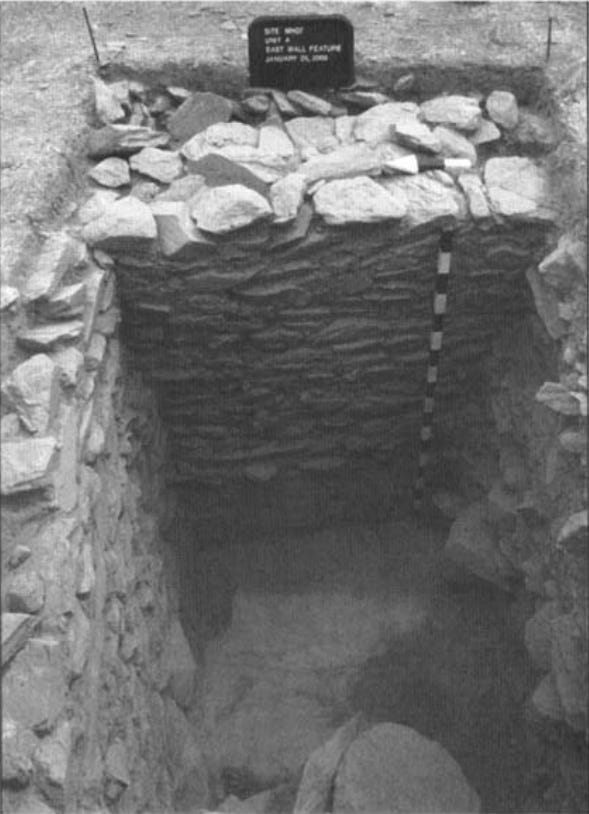

Additionally, remnants of stone walls were discovered, constructed from fieldstones bonded with mud mortar. These walls had once functioned as the dividing line between two adjacent houses. Embedded within the stone wall remains, a bone from a bovid (a family that includes sheep, goats, cattle, and similar animals) was discovered. Radiocarbon dating techniques dated these remains to the period between 770 BC and 380 BC4 .

The site also yielded sculptures that resembled bull’s heads, alongside vessels/pots made of red ware and brown ware.

Red ware pottery is made from clay with high iron content, while brown ware is made from clay with lower iron content.

Evidence pointing to grain farming was detected specifically within the ashe remains in one of the fireplaces at the southern edge of room B. Specifically, wheat and barley seeds were found within these ashes5.

Further, animal remains were also found, indicating the domestication of animals. These findings, coupled with the discovery of fireplaces and large vessels/pots likely used for cooking grains and animal meat, provide a glimpse of the site’s historical domestic and agricultural practices.

Mai Hutsa

The Mai Hutsa site, situated 4km north of Asmara, encompasses an area of 12 hectares. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the site was occupied between 810 BC and 390 BC6.

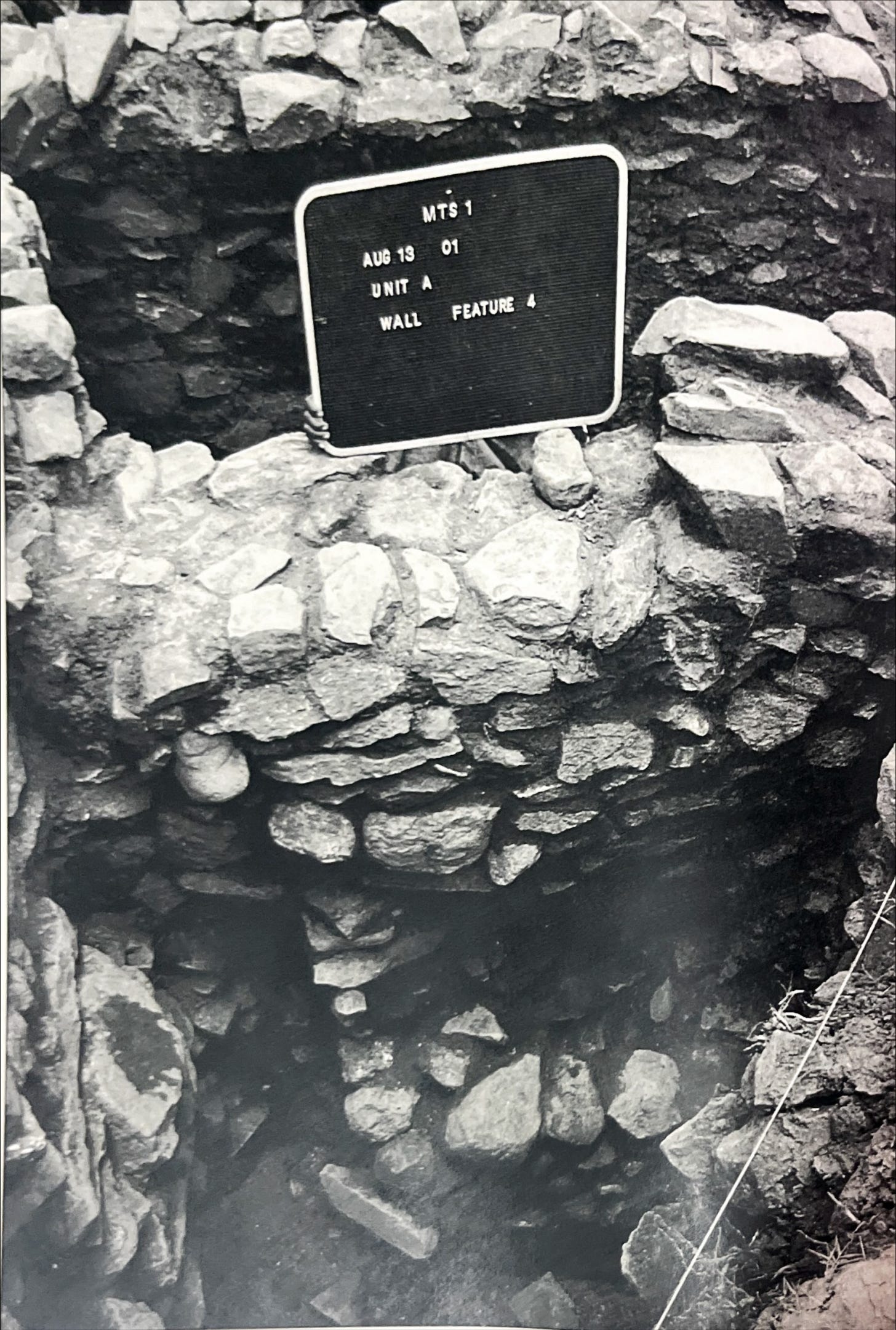

Visible at the site are stone walls, some of which were part of ancient cisterns designed to collect rainwater, while others belonged to residential structures with walls reaching up to 1.7 meters in height. These walls were constructed from fieldstones combined with mud mortar, just like the ones at the Sembel site.

Moreover, evidence of animal husbandry was uncovered, including burned cattle remains and nearby tools7. This suggests that the site was used for domesticating animals and possibly indicates that this particular area was designated for meal preparation.

Mai Chot

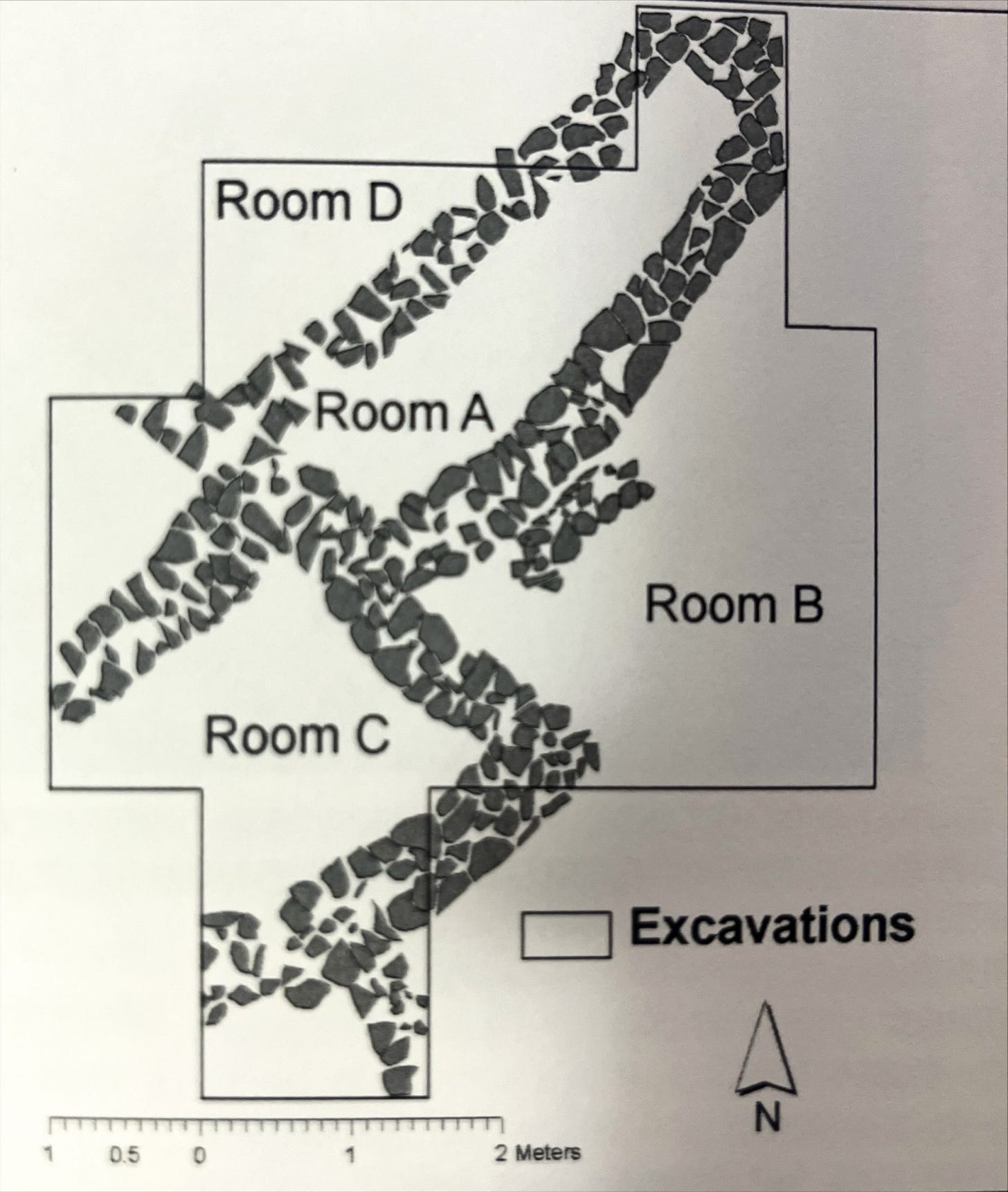

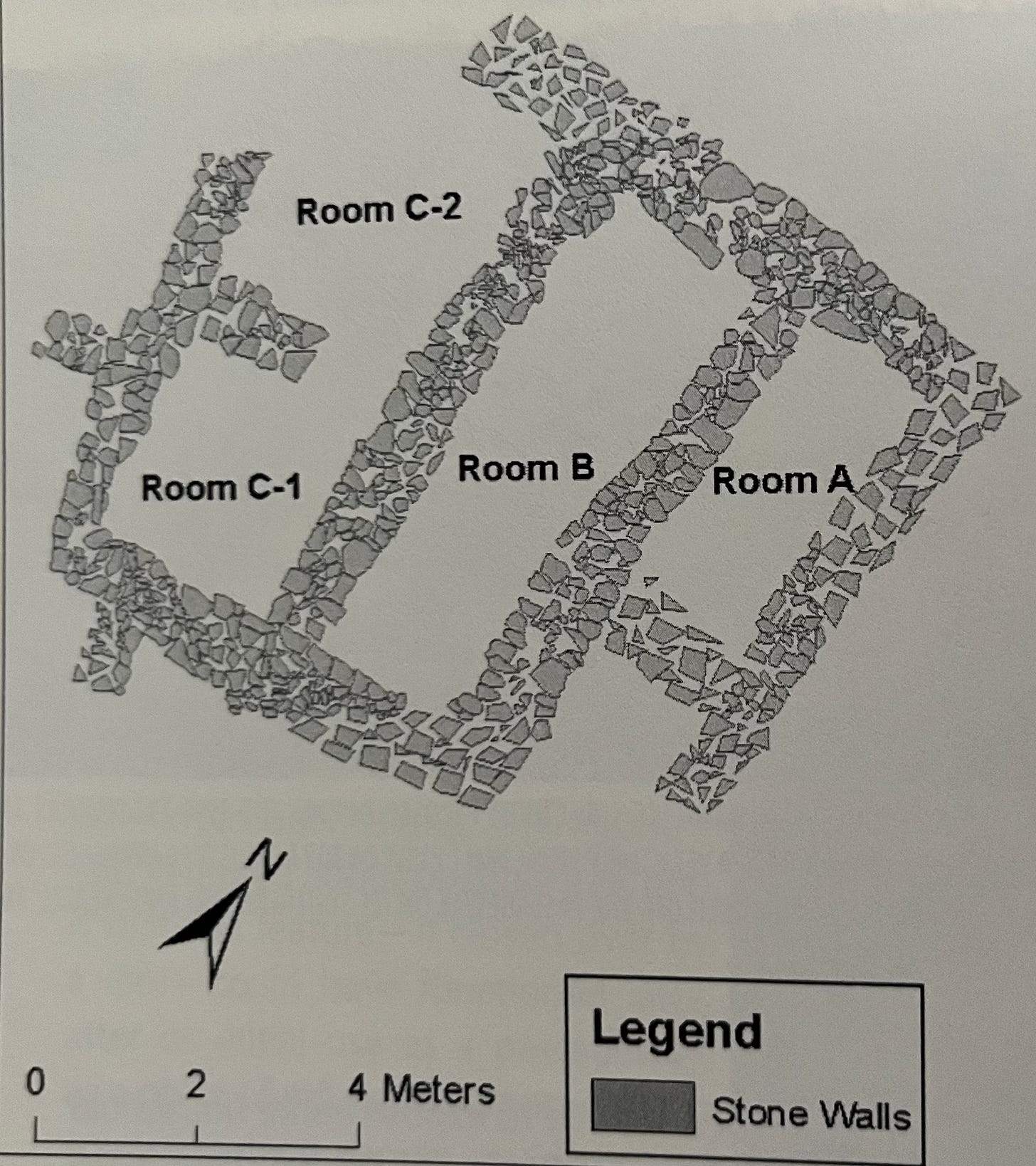

Located to the east of a nearby stream, and near Mai Tsadkan, the Mai Chot site has yielded many important discoveries and has been dated back to the 6th to 4th century BCE, aligning with the latter part of the Ona Culture period8. Among its notable findings were ancient stone walls, indicating the presence of an ancient house with multiple rooms. A particularly interesting room, known as Room A, was 3.8 meters long and featured an odd shape, with no visible entry point. The specific function of this room remains uncertain, though it’s speculated to have served as a “false room,” used as a secret hideaway during times of conflict or social turmoil. These spaces were designed to be discreet, with entry possible only through hidden means, such as movable stones strategically placed at the top of the room9.

However, the artifacts recovered from this room suggest it also functioned primarily as a storage area, notably as the site where a significant number of tiny ceramic vessels, referred to as Tina cups, were discovered. Archaeologists theorize that these Tina cups might have been utilized for storing substances like ghee/butter or even gold (there is a mine located only a few hundred meters away from the site, which contains gold reservoirs)10. Moreover, the room also yielded a large deposit of tools made from obsidian and quartz, adding to the evidence of its storage use within the ancient dwelling.

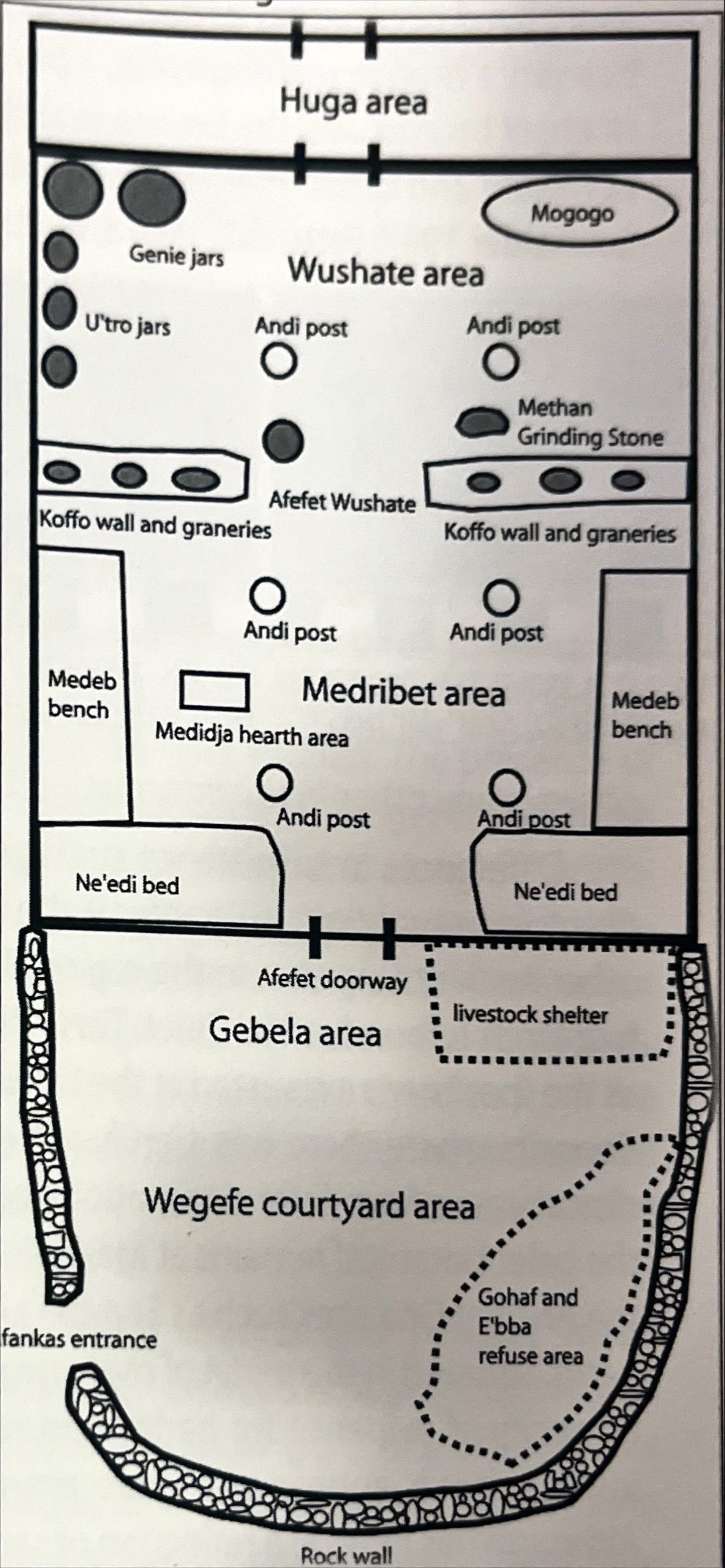

In Room B, adjacent to the wall that divides it from Room A, archaeologists discovered a rock platform. This feature is believed to have served as a bench or “medeb,” a traditional element found in Hidmo houses in Eritrea11, designated for sitting and engaging in conversation. It’s typically situated in the “medribret” area, a communal space within the home used for sleeping, dining, and entertaining guests (a combination of a living room and a bedroom)12.

This finding is particularly fascinating as it offers proof of the medeb bench’s inclusion in Tigrinya Hidmo architecture for over 2,400 years, highlighting its long-standing cultural significance.

The diagram of a Hidmo serves merely as a general depiction of its common features; there isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” arrangement. For those interested learning more about Hidmos, this article is a great introductory piece: https://shabait.com/2021/11/24/hidmo-a-traditional-house-in-eritrean-highlands/

An intriguing aspect of the Mai Chot site is its departure from the characteristics of earlier sites like Sembel and its closer ties to excavations of pre-Aksumite and Aksumite sites conducted in the more southerly regions near Matara and even further south down to Aksum13.

This could indicate the early stages of integration among political, cultural, and social elements in northern Tigray and southern Eritrea, as regional entities began to come together. This period might mark the inception of the D’MT kingdom, particularly around 600-400 BC, coinciding with the occupation of the Mai Chot site.

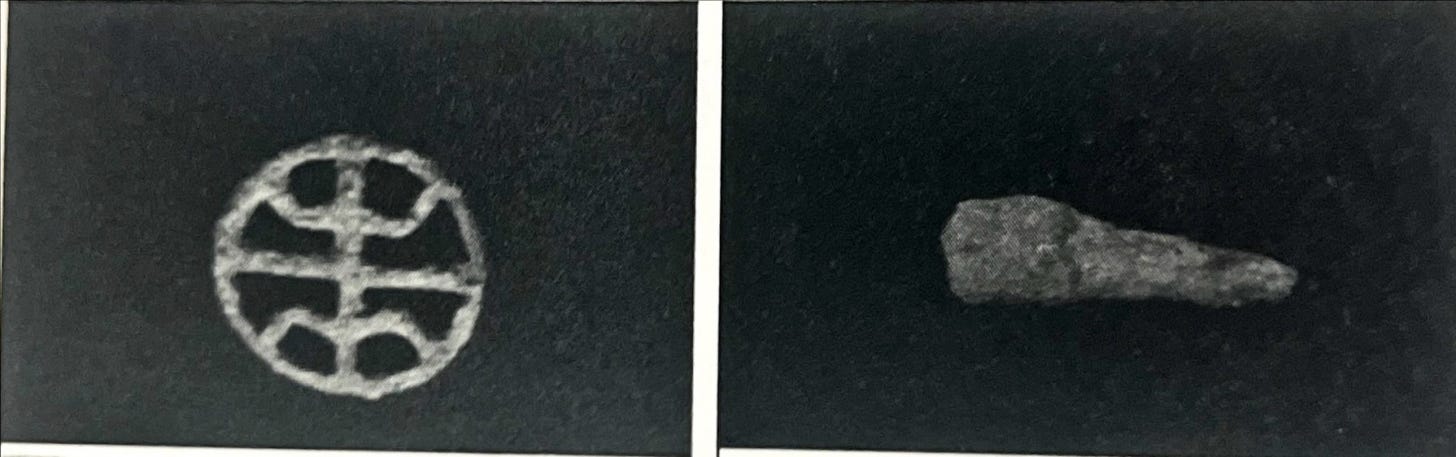

For instance, bronze seals and bronze pins, which were indicators of elite status, have been discovered at Mai Chot. Similar items have also been found at Pre-Aksumite sites located further south.

Mai Chot is distinct for providing the earliest evidence of teff cultivation in the highlands of Eritrea and Ethiopia, setting it apart from other archaeological sites in the region14. Although barley and wheat were also found at Mai Chot, their quantities were smaller compared to those discovered at sites like Sembel and Ona Gudo. Lentils, on the other hand, were frequently encountered. A notable departure from the patterns observed at other Ona sites is the absence of bullhead engravings on rocks at Mai Chot, hinting at a divergent worship or ritual system.

This variation in diet, suggesting a heightened dependence on Teff as the primary cereal source along with an increase in lentil consumption, could indicate a more widespread use of Injera.

Additionally, unique round disks with a central hole were unearthed at Mai Chot. Locals suggested that these artifacts were used as lids for brewing vessels/pots, serving to contain the foam generated during the fermentation of grains like teff. This find not only highlights the community’s brewing practices but also reflects the ingenuity in their approach to managing the fermentation process.

This further supports the notion of Injera being a fundamental component of their diet.

Weki Duba

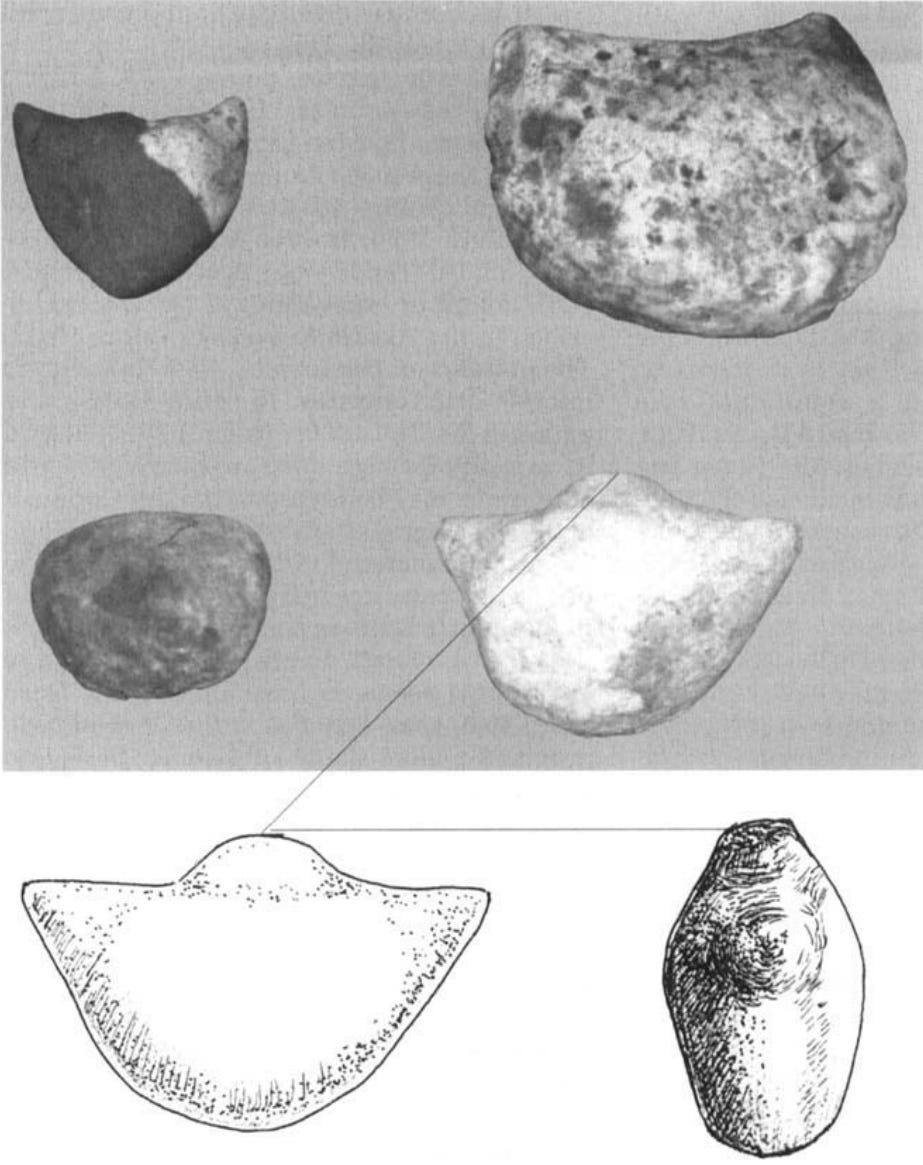

Weki Duba, spanning almost 5 hectares, is identified with the Ona Culture and provides significant insights into the dietary habits of its ancient residents. Among the intriguing finds is a sizable quartz stone, instrumental in crafting Brkuta (ብርኩታ), a traditional delicacy found in certain areas of southern Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. This dish is made by hollowing out wheat or sorghum and cooking it atop a heated, curved stone, showcasing the culinary ingenuity of the region’s ancient inhabitants.

In addition to various ceramic vessels uncovered at Weki Duba, one particularly interesting find is a large spoon, believed to have been used for serving sauces. This artifact not only provides a glimpse into the culinary practices of the time but also suggests a degree of sophistication in meal preparation and consumption among the ancient people of the Ona Culture.

Conclusion

Archaeological exploration of the Ancient Ona culture has been constrained due to geopolitical challenges facing Eritrea, particularly at its southern border. Additionally, the nation’s nascent state necessitates prioritizing funds for essential services, including infrastructure, health, and education. It is hoped that future efforts will illuminate the history of the peoples who once inhabited the area now known as Eritrea. From the scant data available, we understand a distinct society that engaged in the cultivation of cereals like teff, wheat, and barley, domesticated animals such as sheep and cattle, constructed stone dwellings, and in later stages, like those found at Mai Chot, developed status symbols like seals to mark distinctions among the elite.

Bibliography

- Relating the Ancient Ona Culture to the Wider Northern Horn: Discerning Patterns and Problems in the Archaeology of the First Millennium BC, pg 329. ↩︎

- Relating the Ancient Ona Culture to the Wider Northern Horn: Discerning Patterns and Problems in the Archaeology of the First Millennium BC, pg 332. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 109. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 119. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 125. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 130. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 129. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 141. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 141. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 138. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 141. ↩︎

- Hidmo: A traditional House in Eritrean highlands, Ministry Of Information Eritrea ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 145. ↩︎

- The Archaeology Of Eritrea, pg 142. ↩︎