In this article, I will explore the early history of Adulis, covering the period from approximately 300 BC to 200 AD. During this era, Adulis thrived as a prominent city-state, in the Erythraean Sea.

Introduction

Adulis was home to one of the most important trading cities on the Red Sea. Merchants and travellers from as far as Rome & India visited the shores of the Gulf of Zula, where Adulis is located. At its zenith during the reign of Negus ካሌብ/Kaleb in the 6th century, Adulis hosted a fleet of over 60 ships and 100,000 soldiers and served as the launching point for the Aksumite invasion into Himyar. However, this article focuses on the early period of Adulis, specifically from around 300 BC to 200 AD, spanning half a millennium. I will be using both secondary and primary sources, with many primary sources originating from Greek scholars. Additionally, primary sources have been discovered at Adulis itself, which we will explore further.

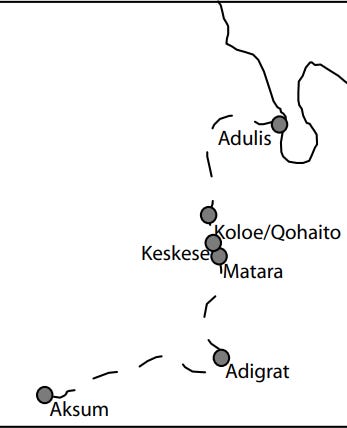

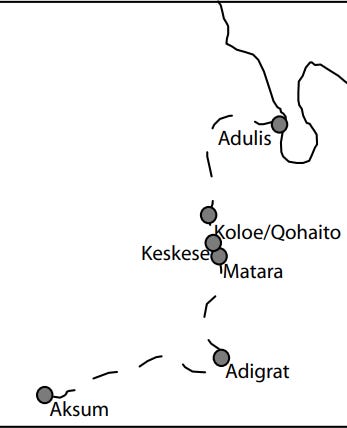

Adulis, now located over 5 kilometres from the Gulf of Zula, was theorized to have been much closer to the sea in ancient times—approximately 3.3 kilometres1. Due to siltation, this ancient city now lies much further from the coast. Adulis is situated next to three rivers, with the northernmost one being the Haddas River, on which Adulis is located above. Merchants used the Haddas River to travel to the town of Qohaito and then to Aksum2.

Adulis served as a bustling port city where merchants conducted trade and local rulers and inhabitants resided. The actual harbour where ships moored was likely a site called Gabaza, as mentioned in the text “Martyrs of Najran,” which describes the 6th century AD military conquest of the Himyarite kingdom by King Kaleb of Aksum. It reads as follows:

The origin of Adulis, likely dates back much earlier. Humans have inhabited the sea coast of modern-day Eritrea, including the Gulf of Zula where Adulis is located, for hundreds of thousands of years. This area was one of the first regions from which modern Homo sapiens branched out of Africa. Much later, the inhabitants near the Gulf of Zula traded back and forth with the other side of the Red Sea. During the Agricultural Revolution and the rise of the Egyptian civilization, it is theorized that one of the main ports of Punt was located near the Gulf of Zula (3rd millennium BC to the 1st millennium BC)3. Subsequently, as the influence of South Arabian kingdoms rose, trading shifted eastwards during the 1st millennium BC.

The Great Stele Of Adulis (~250BC)

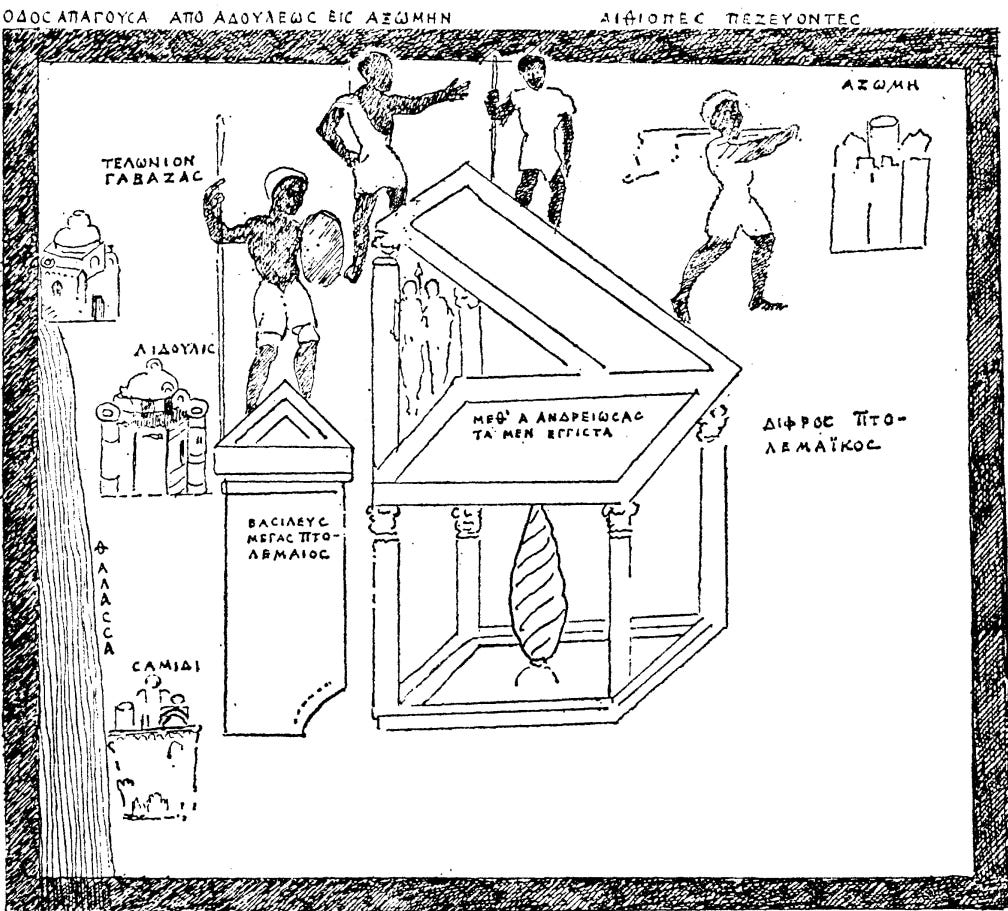

The Structure Of The Stele

When the 6th century Explorer/Merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes ventured to Adulis at around 522 to 523 AD 4 , he came as part of a group of merchants sent forth from Alexandria in Egypt, when he landed at Adulis he remarked at the marble throne that he had observed, this throne had inscriptions written on the sides, in addition to the throne lay a stele made of basalt. Cosmas notes that the Negus ካሌብ/Kaleb had asked the Governor of Adulis (whose name is Abbas), to have a copy of the inscriptions written down and sent to him, then assigned this task to Cosmas and his fellow Merchant Menas, Cosmas and Menas then copied the inscription more than once, with one copy been given to the governor and another kept for themselves. The following excerpt about Adulis is from Cosmas:

Cosmas mistakenly attributes both the Stele and the Throne as being created by the same person and at the same time. However, in reality, scholars believe the Stele was likely erected much earlier than the Throne. The Stele describes the conquests of Ptolemy III, while the inscriptions on the Throne detail the conquests of an indigenous ruler of the land.

It then continues…

In both excerpts, we find information regarding the structural details of the Stele and the Throne. The Throne is said to be made of marble, while the Stele is made of Basalt. Basalt is a common type of volcanic rock found in the Danakil Depression, south of Adulis, so it is plausible that these rocks were mined and used to construct the Stele.

From the above excerpts, we also understand that by the time Cosmas visited Adulis in the 6th century, the stele had been broken and its lower part destroyed. While the exact reason for this remains uncertain, it is highly unlikely that it was left unrepaired due to a lack of will. It is more plausible that the stele was deliberately broken and left in that state because it was disfavored by the local inhabitants of Adulis and the regional king, particularly due to the inscriptions on its lower part. However, we can’t be sure until more evidence is brought to light. We do know that the stele was approximately 1.5 meters tall and had a rectangular shape similar to other steles found throughout the highlands.

Interestingly, Cosmas states that on the back of the chair Hercules and Mercury were depicted, indicating Greek influence in the Pre-Christian belief system in the area.

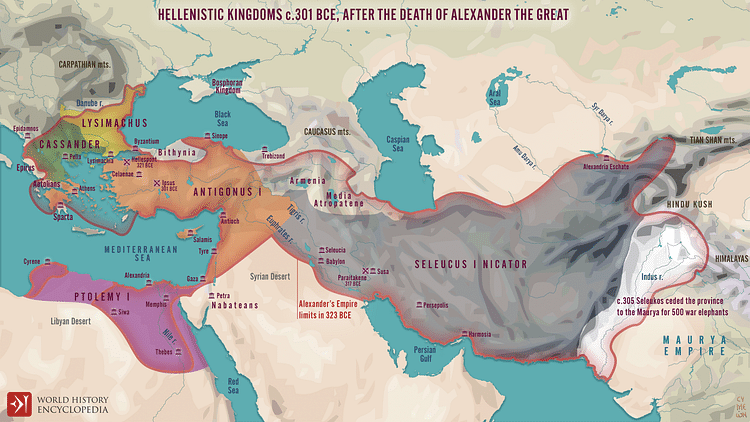

Era Of The Ptolemaic Dynasty

The Ptolemaic Dynasty was a dynasty that ruled Egypt and was founded by Ptolemy I, a general of Alexander the Great, it lasted roughly 300 years (305BC to 30BC)5.

Cosmas then describes the inscription on the stele:

This inscription details the conquests of Ptolemy III, who ruled from 246 to 221 BC. He boasts about his war with the Seleucids, known as the Third Syrian War, and mentions using elephants captured in the lands of the Troglodytes and Ethiopia. As noted later in this article, elephants are a recurring theme mentioned by merchants and travellers to Adulis and its periphery. Ptolemy III indeed led an expedition to Mesopotamia in 246 BC, but there is no evidence that he reached as far as Asia Minor, such as Thrace, or eastward as far as Afghanistan6. These claims likely stem from the conquests of his predecessors, namely Alexander the Great.

During the reign of Ptolemy III, significant advances were made in acquiring elephants from the interior Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands and surrounding areas. These elephants were transported via large boats from Adulis up the Red Sea, in addition to existing trade routes to Elephantine using the Nile. The erection and dedication of the Stele were likely a form of gratitude and appreciation for the use of elephants in their conquests. It is possible that a merchant or traveller to Adulis was tasked with documenting these details, and then placing the Stele.

Elephants In Eritrea

The use of elephants from Adulis by the Ptolemaic dynasty is further evidenced by their deployment in the Battle of Raphia in 217 BC, near modern-day Rafah in Palestine. During this conflict, Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire faced Ptolemy IV of Ptolemaic Egypt. According to the Greek historian Polybius, around 73 African war elephants were involved in the battle. Genetic studies have revealed that these elephants were forest elephants from Eritrea7.

The person who rides an elephant is called a mahout. The mahout sits behind the elephant’s ears and uses a rod to tap the elephant’s ear to command it for different actions. These rods used by mahouts can be found at Adulis.

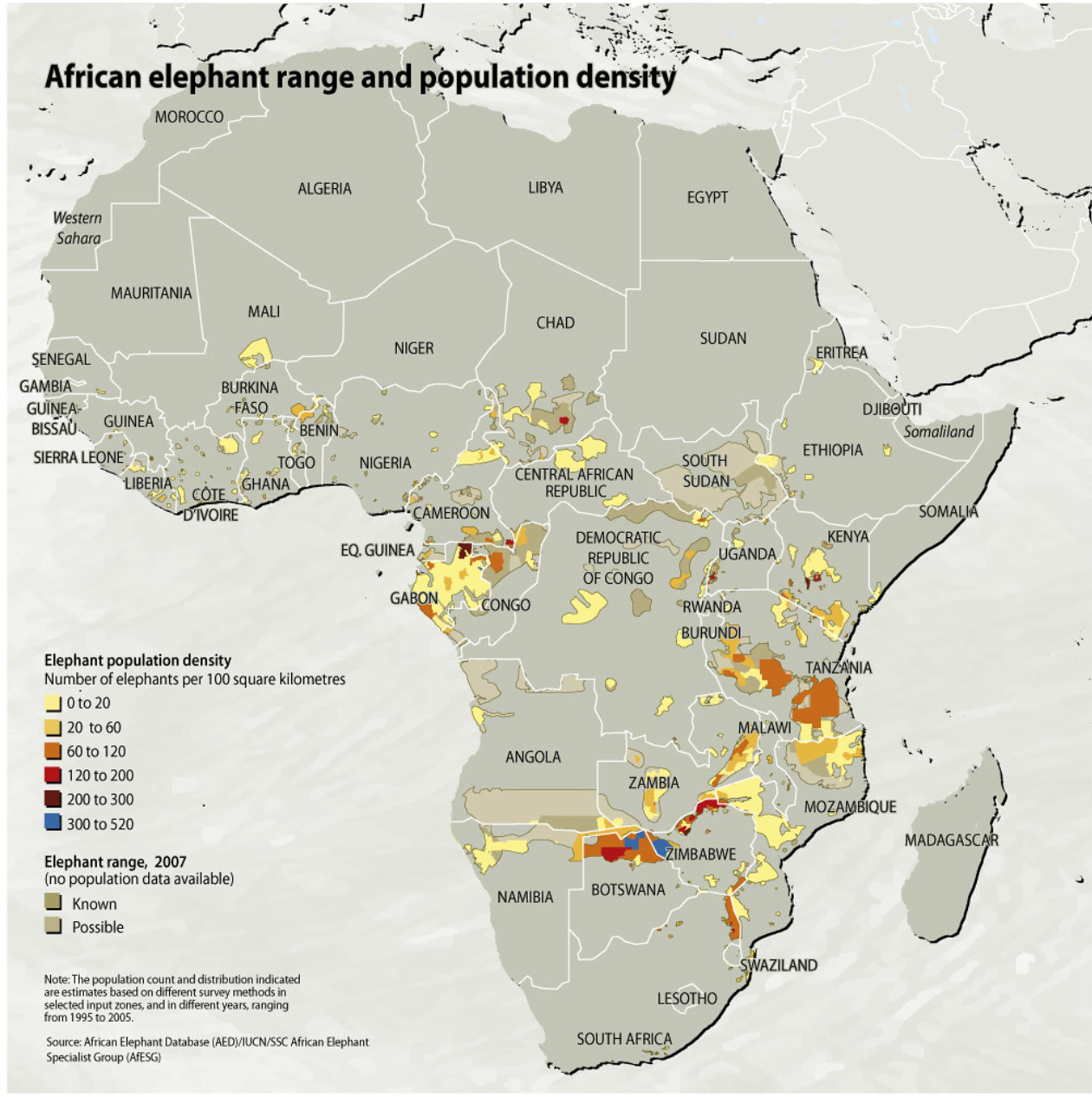

Even in modern times, Eritrea is home to the largest population of Elephants in North Eastern Africa, unfortunately only about a hundred remain, and they’re largely restricted to the Gash-Barka Region of Eritrea.

Pliny The Elder (100 BC – 100AD)

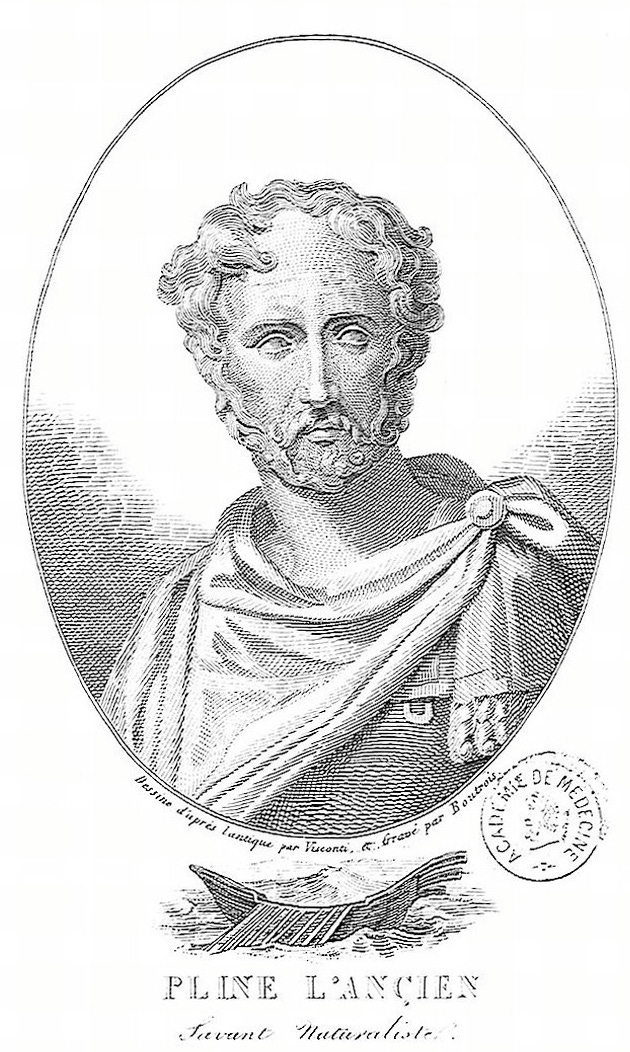

Although Pliny the Elder composed his works around 77 AD, much of his information about Adulis came from the earlier writings of King Juba II of Mauretania, who lived from around 48 BCE to 23 AD8. This connection underscores Adulis’s significance as a port city at least since the 1st century BC, highlighting its importance in regional trade and navigation during this period.

The first mention of Adulis is in the antiquity text named ‘Natural History’ by Pliny The Elder, it was published around 77AD and is the first known encyclopaedia, although not entirely accurate, it does cover various sciences throughout multiple books, Book VI covers geography and has numerous mentions of Adulis, such as:

Origins Of Adulis

Pliny mentions a legend suggesting that Adulis was founded by Egyptian slaves. This tale might be connected to the city’s name, as ‘douloi’ means slaves in Greek, and the prefix ‘a-‘ indicates a lack, thus implying ‘a lack of slaves’9. Although there is no corroborating evidence for this etymology.

The story might also refer to runaway slaves brought to Adulis during the Ptolemaic period, which we discussed earlier, Ptolemaic interest in the region was indeed considerable. It could also date back to the long history of contact between Egypt and Punt. Egyptian Slaves used as workers on boats by merchants might have escaped and integrated with the local inhabitants, leading to this attribution by Pliny the Elder.

However, no evidence has been found of Egyptian slaves establishing the port. It’s more likely that this attribution is a result of the over millennia-old Egyptian trade that occurred via Adulis and the Red Sea, which undoubtedly resulted in population mixing, cultural infusion & have warranted such myths from outsiders to it’s origin.

Also from the excerpt, we can deduce that the items traded at Adulis during this period were primarily animal products. Notably, large quantities of ivory are mentioned, underscoring the continued significant role of elephants in Adulis’ economy.

Maritime Trade

Trade route with Egypt

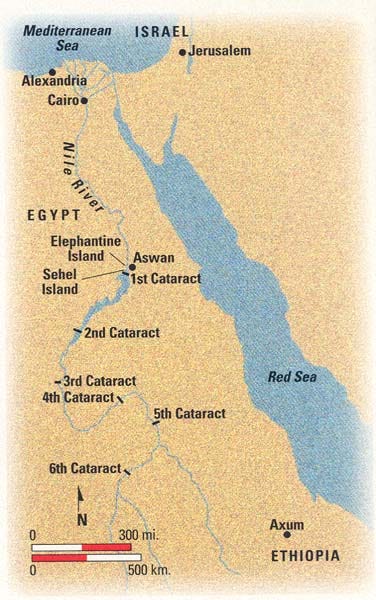

Pliny also describes how both “Ethiopians” and “Troglodytes” engaged in maritime trade with ancient Egyptians. For example, in his writings, he mentions that at the Island of Elephantine, located in Upper Egypt, the Ethiopians would leave their boats and carry them to avoid the rocks at each cataract.

In many of Pliny’s writings, “Aethiopians” refers to the people inhabiting the inland region south of Egypt across the Red Sea. Meanwhile, “Troglodytes” was used to describe the peoples living near the coast.

It is highly likely that trade with Egypt occurred through an inland route, utilizing the tributary rivers of the Nile and navigating through the cataracts. This trade route was most probably established as far back as Puntite times.

Early Adulis Boats

Pliny also describes some of the vessels used by the Troglodytes for maritime activities. Specifically, he details how cinnamon was acquired by the Aethiopians and then traded by the Troglodytes across the sea using simple boats that lacked sails or oars, relying instead on the natural winds to guide them across the Arabian seas. In return, they received goods such as glass, and copper, and highly demanded items like necklaces. The excerpt reads as follows:

The Gebbantiae were likely a group in Southern Arabia, next to the Sabaeans and Hydramiates10. Ocelis is located near the Bāb al‑Mandab strait and is frequently used to set sail onwards to India11. The fact that it takes nearly five years for merchants from Adulis to return suggests they were travelling vast distances, possibly as far as India.

Notably, by around 500 AD, Cosmas confirms that merchants from Adulis were present in Sri Lanka. Therefore, it is not far-fetched to consider that Adulite merchants may have been undertaking such extensive journeys even earlier.

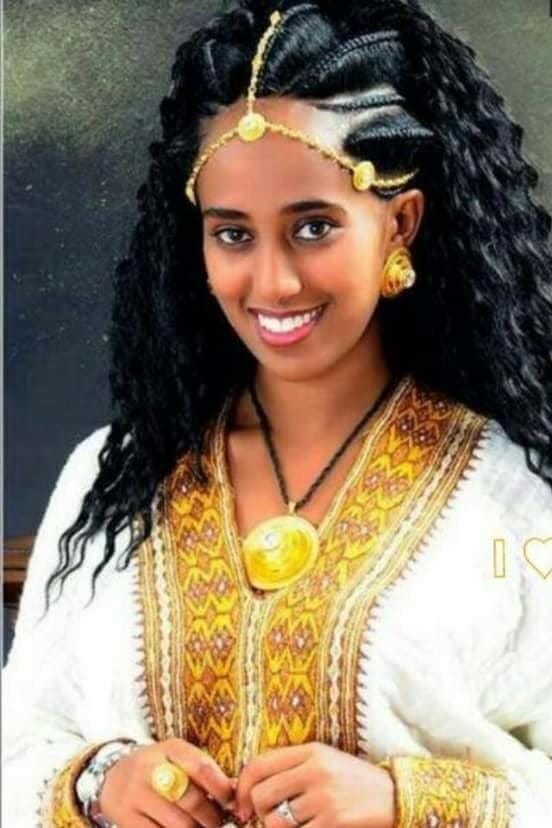

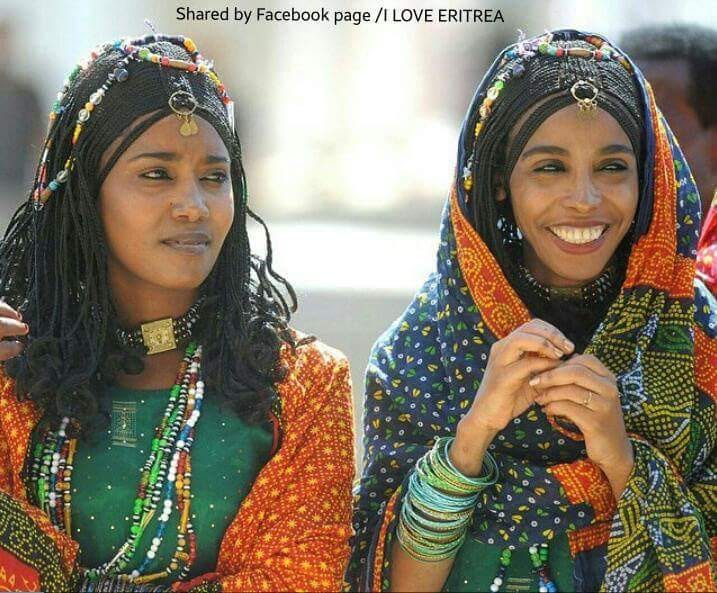

Pliny mentions that merchants from Adulis imported raw materials such as glass and copper, in addition to clothing, which likely refers to garments of some sort (as we will find out later in this article). Additionally, they traded accessory and luxury items like bracelets and necklaces. These items, especially bracelets and necklaces, continue to be significant pieces of jewellery for women throughout Eritrea, across all tribes, these trade goods highlight the long-standing cultural importance and continuity of such adornments in the region.

Adulis Market’s

So where did the merchants bring their clothes, textiles, raw materials, and other trading goods after docking their ships at the port of Gabaza? And where would merchants from Adulis, Aksum, and surrounding states bring their goods to trade at Adulis?

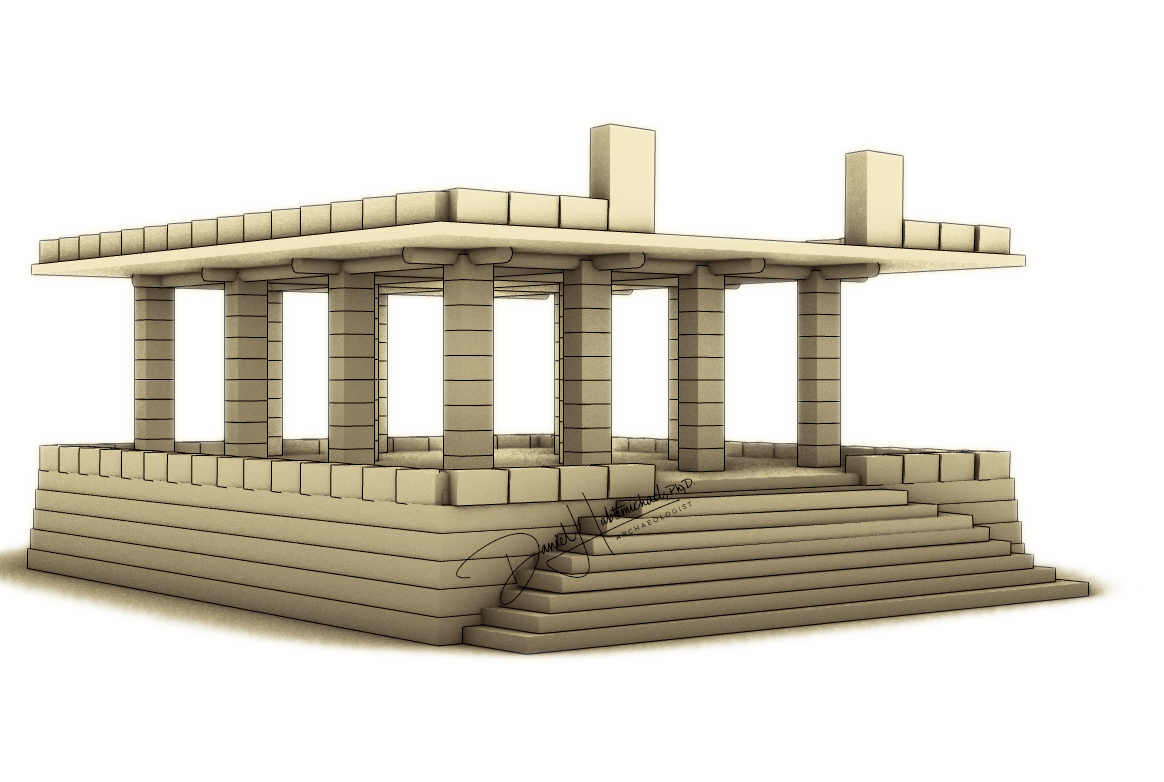

Much of this trade likely occurred at markets in and around Adulis. For instance, archaeological remains of one such market were discovered by Dr. Daniel Habtemichael. The remnants of the pillars that once supported the roof indicate the market was 18.12 meters by 15.40 meters, with a lower storage area for goods.

Periplus of the Erythraen Sea (50AD-100AD)

Interesting fact: a periplus is essentially an ancient Greek travel guide for merchants. The term ‘Erythraean’ (meaning red) was commonly used by the ancient Greeks to refer to the modern-day Red Sea and parts of the Gulf of Aden. Therefore, when you combine the two, you get a guide for the Red Sea.

Modern day Eritrea, get’s its name from The Erythraen Sea.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is another ancient Greek text that provides insights into Adulis. It details not only the city itself but also the journey taken by merchants and travellers deeper inland to Qohaito and then to Aksum. For example the following excerpt describes the animals that were hunted both inland and near the Adulis coast, specifically mentioning elephants being hunted and tortoise shells being found on the nearby islands. The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea, authorship is disputed however a date ranging from ~50AD to ~100AD has been suggested, with 60 AD being proposed by Wilfred Harvey Schoff12. The following is an excerpt:

A lot of important information can be gleaned from the excerpt above, such as fauna that lived near Adulis at the time, in particular, elephants are mentioned, although elephants in modern-day Eritrea are largely restricted to the Gash Barka Zone in the far west of Eritrea, during antiquity Elephants were in much more abundance, and as the author of the Periplus mentions, could even be found at Adulis. Evidence of artifacts from elephants can be found throughout Adulis.

The King Of The Erythraean Sea Zoskales

The author of the Periplus of the Erythraen Sea also gives insight into the proposed ruler of a vast region encompassing, modern-day Eritrea, Sudan, Northern Ethiopia, Djoubti, and Northern Somaliland. The excerpt is as follows:

A stadia, an ancient Greek unit of measurement, typically ranges between 150 and 200 meters. This context provides a basis for understanding the distances described in the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.”

Mapping Zoskales’ Kingdom

From Berenice to Aqiq

Berenice Troglodytica, located in modern-day Egypt, was an important port city in ancient times. When travelling south from Berenice for around 600-800 kilometers (3000 stadia), one would reach a region near modern-day Aqiq in Sudan, also referred to as the Gulf of Agig.

This location is historically significant as it corresponds to Ptolemais Hunts/Theron, a small market town known for its role in the ancient trade networks.

Ptolemais Hunts/Theron to Adulis

From Ptolemais Theron, continuing another 450km-600 km (~3000 stadia), travellers would reach Adulis, an ancient port city in what is now Eritrea. This distance aligns with the current geographical calculations of around ~400 kilometres from the initial starting point, supporting the historical accuracy of the Periplus’s descriptions.

Deep Bay and Obsidian Source

The Periplus mentions a deep bay where obsidian stone was found. This location, approximately 800 stadia or about 120-160 kilometres from the previous point, might correspond with modern-day Mersa Fatuma.

Obsidian, a volcanic glass used in various tools and trade, was a significant resource in ancient times, especially in Adulis.

Dominion of Zoskales

The territories described by the author of the Periplus were under the control of Zoskales. Specifically the area described extends from the “Calf-Eaters” to the “Other Berbers.”

From this place the Arabian Gulf trends toward the east and becomes narrowest just before the Gulf of Avalites. After about four thousand stadia, for those sailing eastward along the same coast, there are other Berber market-towns, known as the “far-side” ports; lying at intervals one after the other, without harbors but having roadsteads where ships can anchor and lie in good weather. – The Periplus Of The Erythreaen Sea, Paragraph 7

The Calf Eaters are mentioned to be below Bernice. While the “Other Berbers” are referenced in relation to market towns near the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, a strategic point at the narrowest part of the Arabian Gulf. This region is close to the entrance of the Red Sea, just before reaching Avalites. The area likely encompasses regions from modern-day Assab in Eritrea up to Berbera in Somaliland.

Zoskales’ Character

Interestingly, in the excerpt, the author mentions Zoskales, describing him as miserly in his ways and always driven by greed, possibly indicating a tyrant ruler with ambitions for conquest. He also notes that Zoskales was familiar with Greek literature. This is significant because, as mentioned earlier in the article, Cosmas found inscriptions in ancient Greek on the throne and the stele behind it in Adulis. It is strongly suggested that the elites, such as Zoskales were bilingual and proficient in both the indigenous Ge’ez language and Greek. This is not surprising, given that the kingdom was a port city visited by merchants from various backgrounds, with Greek being the lingua franca for many merchants and travellers during that period.

Kings Residence

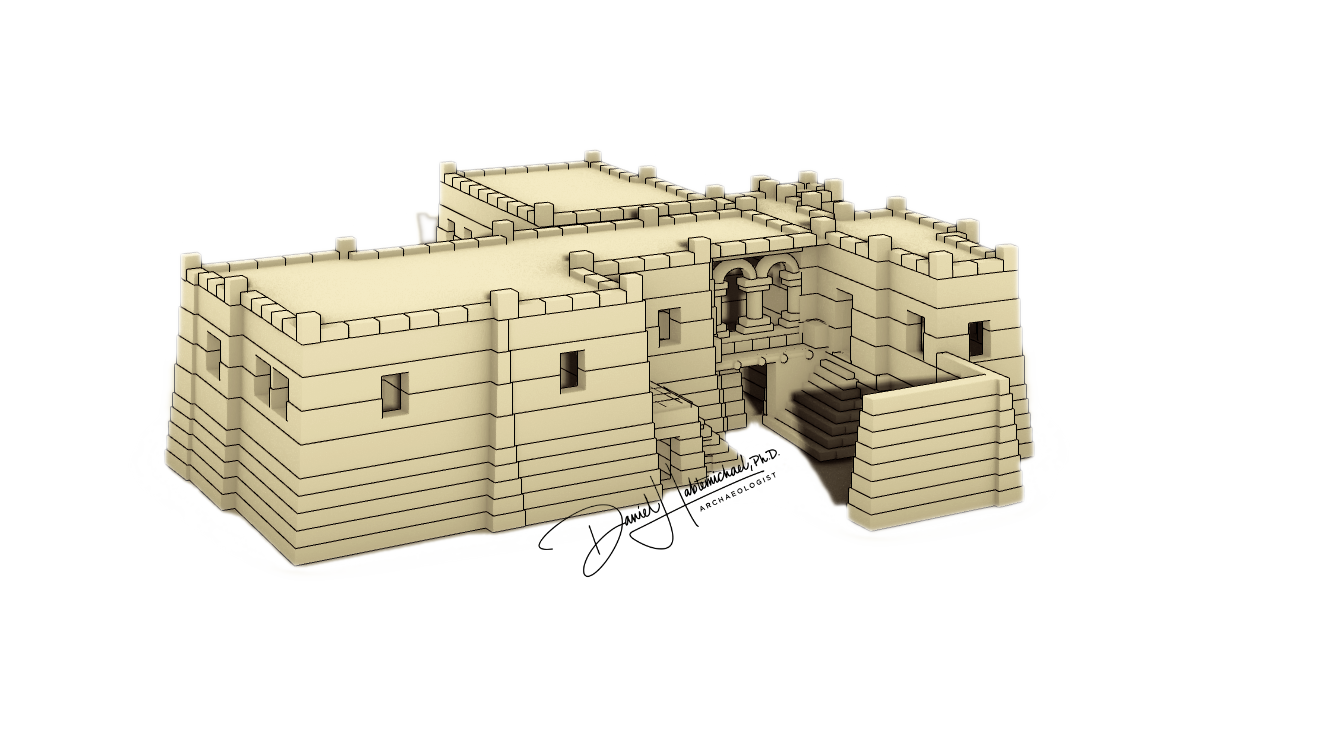

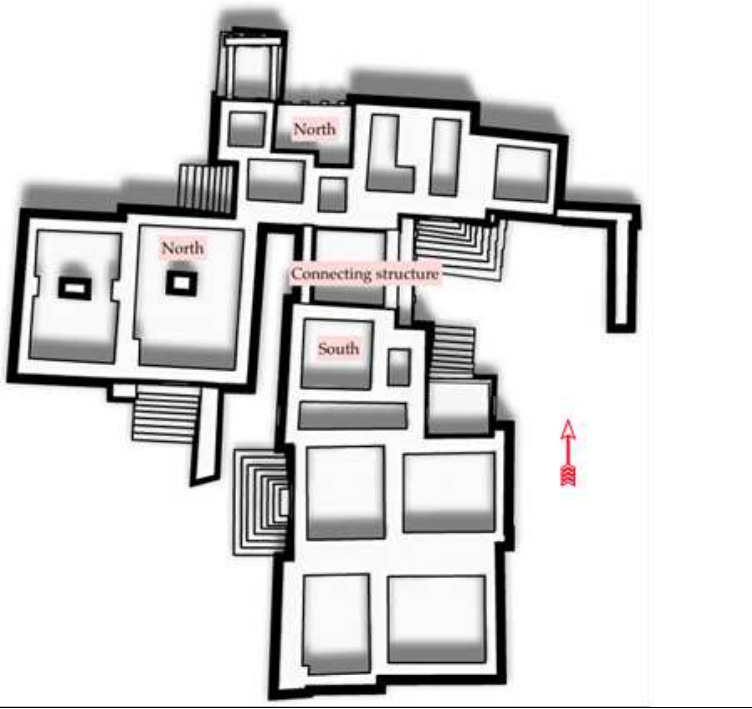

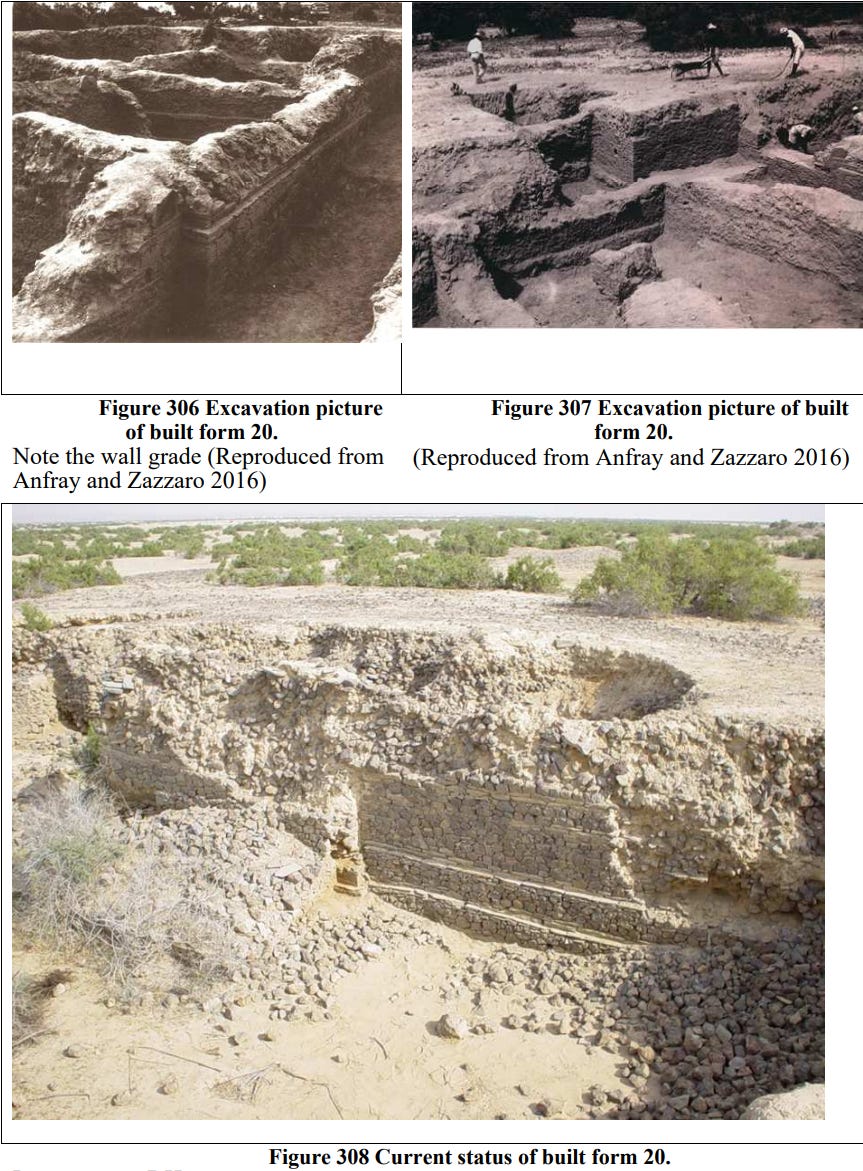

Originally excavated in the early 1960s by the Ethiopian Institute of Archaeology, the King’s Residence at Adulis consists of a single-story building with several rooms and a balcony. According to Dr. Daniel Habtemichael, the northern section of the building was constructed at a later period. Therefore, during the earlier period of Adulis, when Emperor Zoskales lived, the building was composed solely of the southern structure.

Adulis Trade During the First Century AD

The author of the Periplus discusses the trade that took place in this region. He specifically mentions the items imported into these lands and provides a brief overview of what was exported. This information offers valuable insights into what the people in Zoskales’ domain valued and desired.

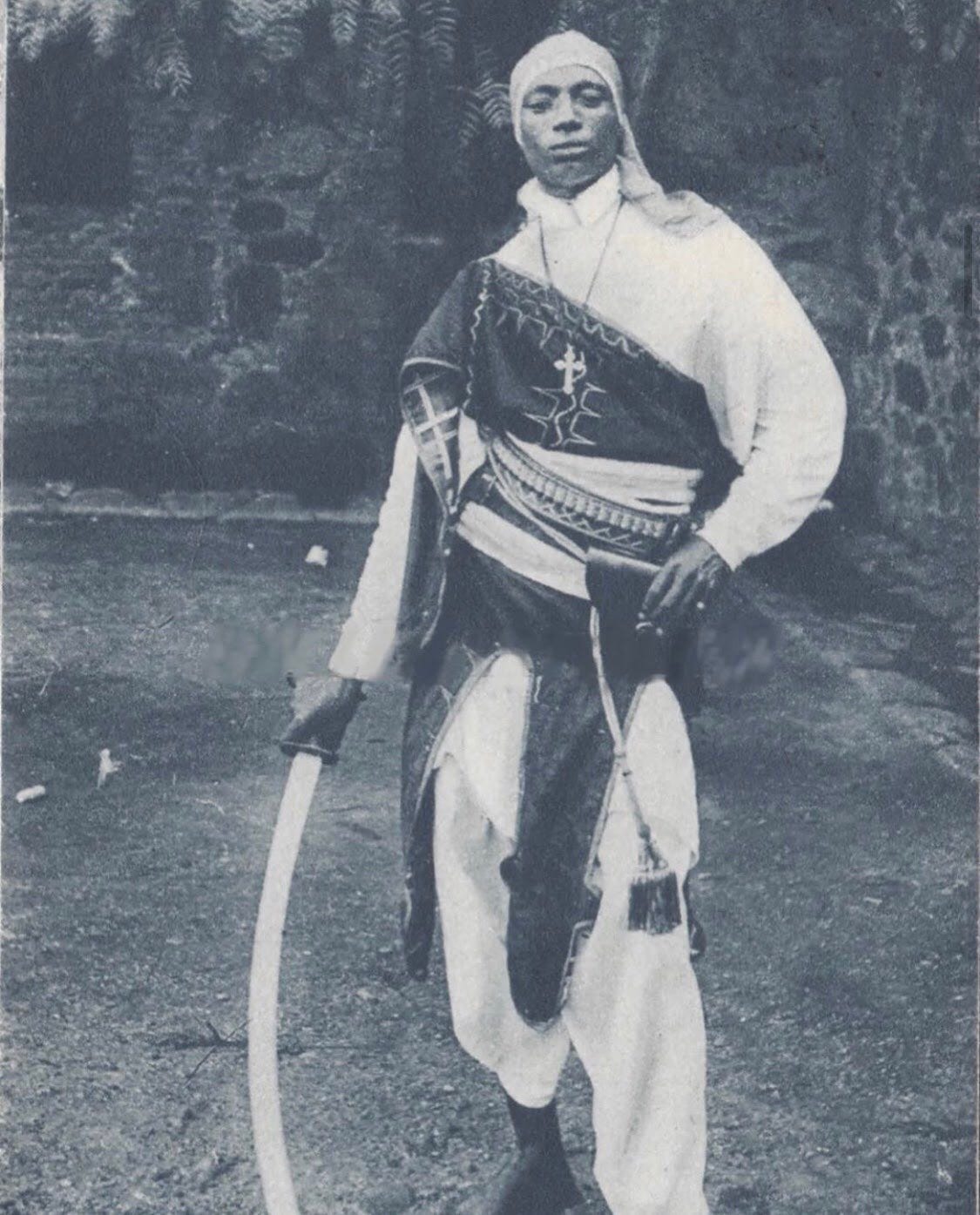

The cultural fusion that occurred in terms of clothing, in Adulis from Greece & India and vice versa can’t be understated, this excerpt in conjunction with the others mentioned in this article give a brief insight into this.

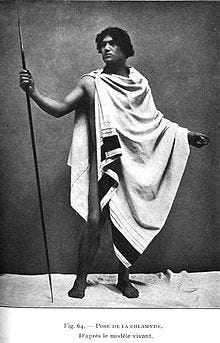

Clothing and Textiles

The author of the Periplus of the Red Sea provides detailed descriptions of the clothing and textiles prevalent in the dominion of Zoskales and its neighbouring regions. He notes that clothes were commonly imported from Egypt, particularly robes from Arsinoe, a city situated near the Gulf of Suez at the northern end of the Red Sea. These robes were notable for their quality and were a significant part of the trade. Additionally, linen mantles were another form of clothing mentioned. These mantles were essentially garments made from linen and wool, with cloaks that covered the head, providing both comfort and protection from the sun.

Materials and Manufacturing

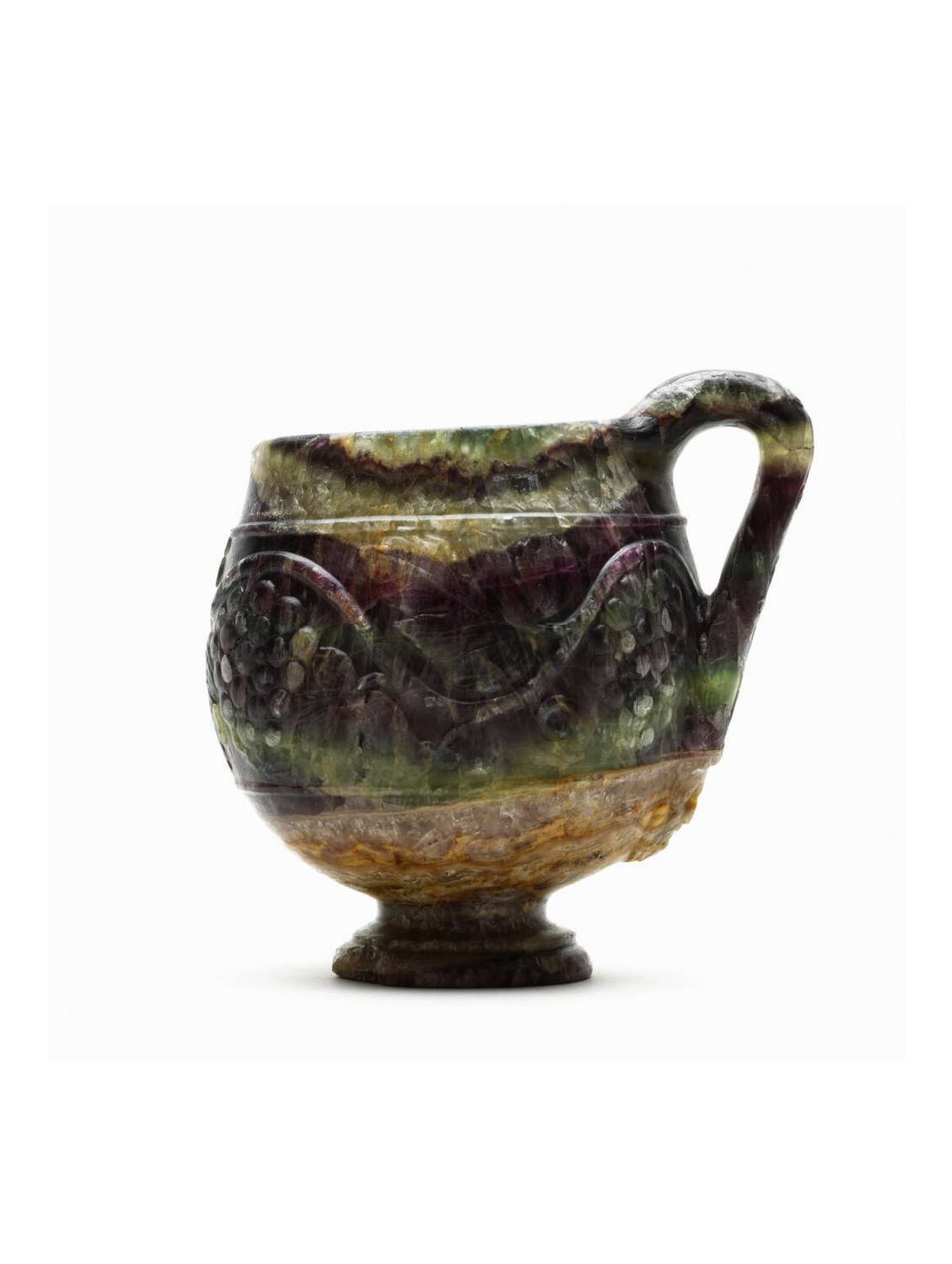

The text also discusses various materials used in ancient manufacturing. Flint glass and murrhine, which is a mysterious substance utilized in ancient Greece and Rome, which were commonly crafted into vases and cups. These materials were prized for their unique, often discoloured appearance, which added to their aesthetic value.

Metallurgy and Tools

The city of Diospolis, located in Upper Egypt, is highlighted for its association with brass. Brass was a versatile metal used for making ornaments and coins, which facilitated trade. Sheets of soft copper were also mentioned; these were employed by locals to create cooking utensils, drinking cups, and accessories such as bracelets and anklets for women.

Iron was an important import, used extensively for making spears. These spears were not only employed in hunting elephants for ivory but were also essential weapons in warfare, particularly in the kingdom of Zoskales. Other metal tools like axes and swords were also in use, indicating a sophisticated level of metalworking.

Wine and Luxury Items

A limited amount of wine was imported from Laodicea (modern-day Turkey) and Italy, primarily reserved for the royalty, such as King Zoskales. Additionally, gold and silver plates, intricately decorated in the cultural styles of his dominion, were part of the luxury items for the king. Military cloaks, likely chlamys made of wool, were used by the military, hunters, horsemen, and travellers in ancient Greece, and thus likewise were probably used by similar groups in Adulis and it’s periphery. The text also mentions coats of animal skins, which were probably worn for additional layers of protection.

Trade with India

Ariaca, a region in ancient India, is noted for its exports to the Red Sea region. Indian iron, steel, and cotton were highly valued imports. The author also mentions specific fabrics, such as mallow-coloured (purple) cloth and coloured lac, a dye made from insects that produce a reddish colour. These fabrics and dyes were significant for their quality and colour, which were highly prized in ancient textile markets.

Exports from the Kingdom of Zoskales

From the dominion of Emperor Zoskales, significant exports included ivory, tortoiseshell, and rhinoceros horn. These items were collected at Adulis and its surrounding areas, as corroborated by multiple texts from that era. The trade in these valuable commodities highlights the region’s rich natural resources and its strategic importance in ancient trade networks.

Seasonal Trade Patterns

The author notes that most imports from Egypt occurred from January to September. This seasonal pattern likely aligned with favourable weather conditions and navigational considerations, optimizing the efficiency and safety of maritime trade routes.

Religion

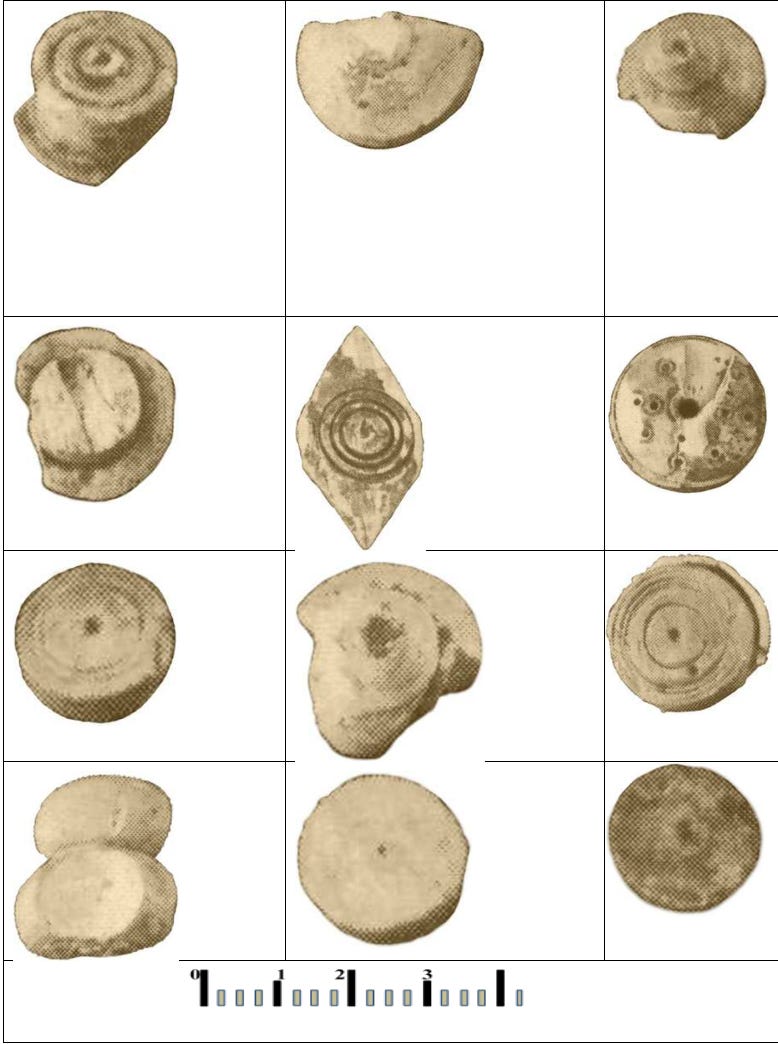

Introduction to Adulis Ceramics

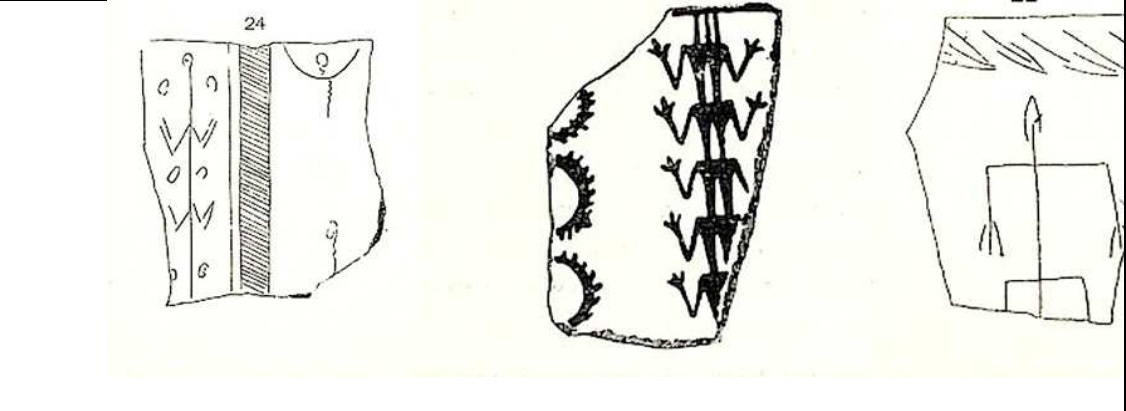

While direct information on the religious rituals in Adulis is limited, we can infer some practices by analyzing ceramic evidence found at the site. These ceramics, despite the uncertainty in their precise dating, provide valuable clues about the religious and cultural practices during the earliest occupation periods at Adulis.

Ceramic Evidence and Ritual Depictions

Several pottery shards discovered at Adulis depict figures engaged in what appear to be ritualistic gestures. The first two shards show figures with both arms raised in a circular motion above their heads. The last shard features a figure with both arms extended downward at a right angle. These depictions suggest specific ceremonial actions that might have been part of religious or social rituals.

Correlation with Later Eritrean Practices

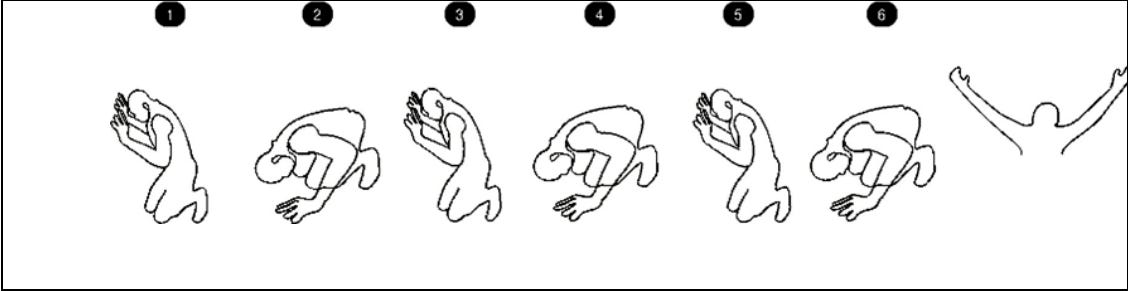

To understand these gestures better, we can look at known practices in the Eritrean region from later periods. According to Daniel Habtemichael’s work, “Modeling the Local Political Economy of Adulis” (page 310), Eritrean Neguses (Bahr Negus) were traditionally greeted with a specific sequence of movements:

- Bending the knees.

- Raising arms in a circular motion above their heads.

- Striking the ground with the arms.

- Bowing, then returning to an upright position.

- Repeating this sequence six times.

- Finally, raising both hands to the sky.

This ritual sequence, particularly the final act of raising both hands to the sky, is significant in understanding regional religious practices. The described gestures are consistent with those depicted on the Adulis pottery shards.

Historical and Cultural Significance

These ritualistic gestures were not isolated to a single period but were seen throughout the region during Greco-Roman antiquity and the Aksumite pre-Christian period. One of the earliest examples of such gestures is found on the Hawulti Stele in Eritrea, which contains the first known Ge’ez inscription. The stele depicts figures in poses similar to those on the Adulis ceramics, suggesting a long-standing cultural and religious tradition. Many Aksumite coins were also minted with the same symbol.

Arwe and The Importances of Elephants

In the context of the wider region around Adulis, extending into the highlands up to Aksum, oral traditions dating back to Greco-Roman times recount the tale of Arwe, a large serpent-like creature that once ruled the region. This serpent prevented people from crossing the Red Sea. According to the tradition, a brave man, mounted on an elephant, managed to kill Arwe. The use of the elephant as the hero’s mount is significant, as the main export from Adulis at the time was ivory-related products, including elephants for warfare. The oral tradition is as follows:

Interestingly, the Ancient Egyptians also wrote about a giant serpent that ruled over Punt, as described in the Ancient Egyptian story “The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor: An Egyptian Epic.” This is briefly covered in my Punt Article. The mention of such a serpent in external sources during earlier Puntite times suggests that this belief may reflect even more ancient practices predating Greco-Roman times. Notably, the hero in the story used an elephant, a significant commodity in Adulis and Aksum, to defeat the mystical serpent. This connection underscores the longstanding cultural and economic importance of elephants in the region.

Conclusion

Adulis stands out as one of the earliest political city-state entities in the Horn of Africa. From its inception, Adulis engaged in extensive trade with neighbouring regions, establishing itself as a significant commercial hub. The city’s trade routes extended both overland and across the sea, reaching the Arabian Peninsula, and traversing the Red Sea to Egypt. Over time, Adulis expanded its trading network to include interactions with the Greeks and Indians. This extensive trade is well-documented by Greek merchants and travellers who visited and recorded their observations of the city.

During a period of time, Adulis was governed by an emperor named Zoskales, who wielded authority over a vast expanse of territories. Zoskales’ reign is noted for its influence on the cultural and economic landscape of the region. The city’s prominence during his rule underscores its strategic importance in ancient trade networks.

As detailed in this article, many contemporary cultural practices in Eritrea and Ethiopia, especially in terms of clothing, can trace their origins back to this historical period.

The name “Eritrea” itself and the emergence of the first city-state in the Erythraean Sea are rooted in this era. The legacy of Adulis is evident in the enduring cultural and historical influences that continue to shape the region today.

Sources Used

I have used various sources when researching and composing this article, however, my main sources consisted of the following 3 texts:

- Modelling the Local Political Economy of Adulis by Dr Daniel Habtemichael. This is a Doctoral dissertation that covers all aspects of Adulis, this is probably the most comprehensive text about Adulis to date, Habtemichael is an Eritrean Archaeologist, who has excavated multiple ancient sites in Eritrea, including Adulis. This is an incredible piece of research.

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam by G.W. Bowersock. This book was a great introductory text into Adulis, it covers all periods of Adulis. It also gives important insight into the inscriptions found at Adulis.

- The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis and the Eritrean Coastal Region by Chiara Zazzaro, This research paper has an in-depth analysis of many artifacts (including images) found at Adulis, in addition to giving a brief insight into the history of Adulis.

This website, created by Daniel Habtemichael, contains many illustrations of various buildings found at Adulis, including an interactive map. Highly recommend checking it out: https://www.adulites.com/IntroAdulis/

Bibliography

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 11 ↩︎

- The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis and the Eritrean Coastal Region, pg 3. ↩︎

- The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis and the Eritrean Coastal Region, pg 2. ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 25 ↩︎

- https://www.worldhistory.org/Ptolemaic_Dynasty/ ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 42 ↩︎

- The Elephants of Gash-Barka, Eritrea: Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Patterns ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 27 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 8 ↩︎

- Pliny’s Gebbanitae by A.F.L. Beeston, pg 160 ↩︎

- A likely identification of “Sambrachate, and a homonymous city on the continent, 3,7. ↩︎

- The Periplus Of The Erythreaen Sea, Translated from the Greek and annotated by Wilfred H. Schoff, pg 15. ↩︎