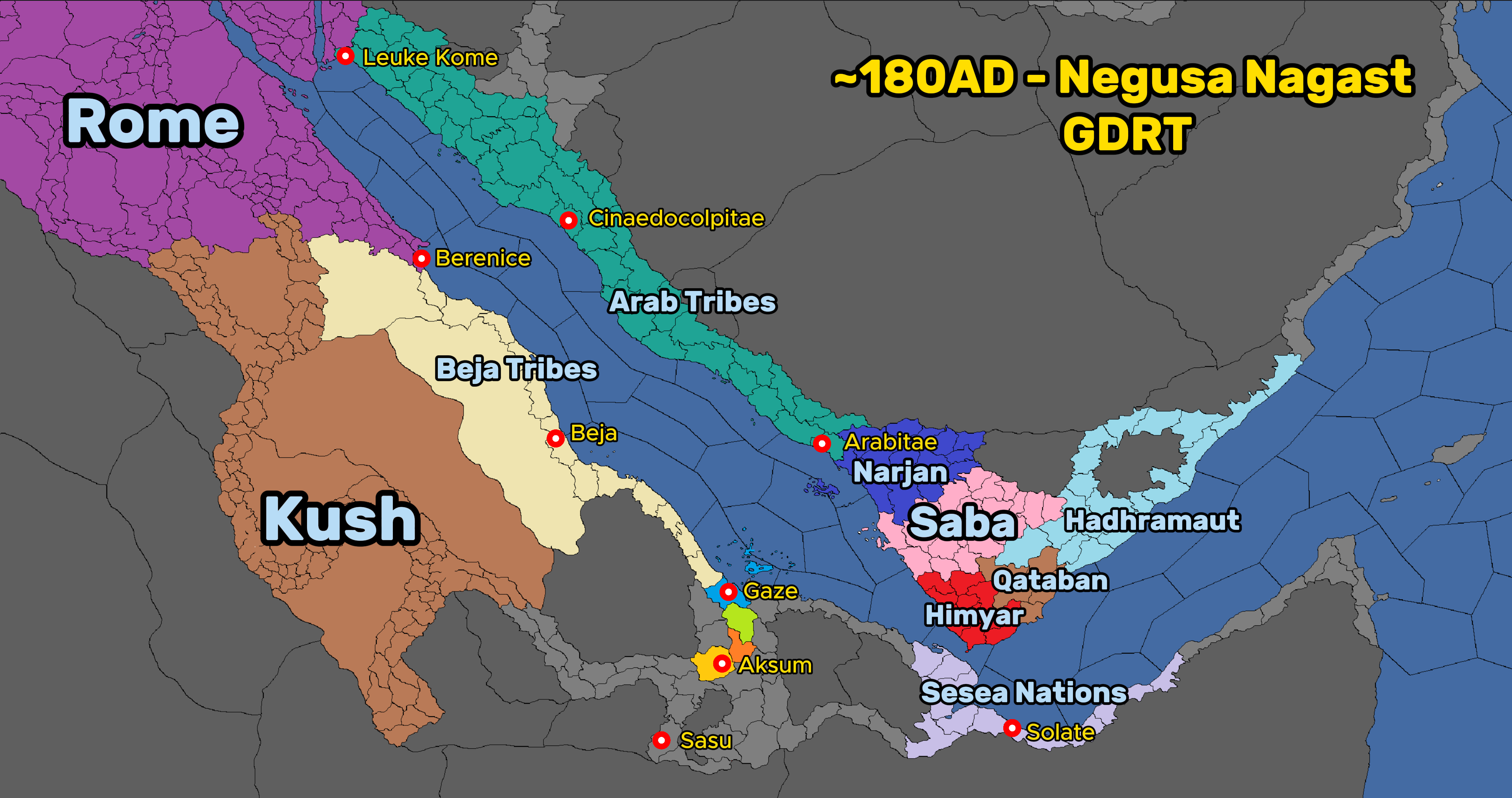

Emepror GDRT was one of the greatest conquerors the horn of africa has ever seen. During his reign, he united the fragmented habesha city-states and expanded his empire around the NE Africa & Arabia.

Reader Note:

As with many events in classical history, we may never know what truly happened. This uncertainty is exacerbated by the removal of the section detailing the king’s name on the throne by the time Cosmas copied the inscription in the 6th century AD. Some claim the Aksumite king Sembrouthes wrote the inscription, while others attribute it to a king of Adulis. Although we may never be certain, we can make educated guesses using the available information. It’s important to remain unbiased when analyzing historical data. Regardless of whether the emperor inscribed on the throne was from Aksum, Adulis, or elsewhere, it does not diminish his status as a great conqueror from the region who ushered in a new era. This empire not only thrived throughout the classical age via the Aksumite Empire but also persisted for millennia through the Zagwe Kingdom, Solomonic Dynasty, and Medri Bahri. Hopefully as more archaeological work is done, we can better understand the past in our region.I have used a variety of primary and secondary sources as the basis of this article. Citations and links to the sources are attached to assist you in making your own judgment.

While the Sabaean inscriptions mention that he referred to himself as the King of the Habeshites, it’s important to remember that this was nearly 2000 years ago. Since that time, peripheral tribes in the area had intermixed with the Habeshas and were also related to Aksum. Additionally, during GDRT’s later conquests, he mentioned lands inhabited by Nilotics, Cushitics, and Arabs. Aksum was a multi-ethnic empire, even if its core was located in Habesha lands and its rulers were of Habesha descent. All people encompassing the modern day region of the horn and southern arabia can be proud of Aksum past.

Table Of Contents

Introduction

The Aksumite Empire, with roots dating back to 800 BC in pre-Aksumite sites1 (For more info read my article on Yeha), began in and around Aksum, Adulis, Yeha and the surrounding regions. Around the turn of the Anno Domini, it rose from humble beginnings to become one of the greatest empires of its time, lasting until around the 8th century AD. Its immense power during the latter part of the first millennium was noted by the Persian Manichean prophet Mani, who stated in the 3rd century AD that the Aksumite Empire was one of the most influential empires of that era. Negus GDRT (vocalized as Gadarat) was the first Aksumite emperor mentioned in any inscriptions, and it was likely during his reign that the city-state of Aksum grew to encompass the largest empire the Horn of Africa has ever known.

This article discusses the rise of the great Aksumite Empire, focusing on the period from approximately 50AD to 220 AD. During this time, Aksum was a rapidly growing city-state, trading ivory, gold, salt, and other resources obtained from its surroundings, as well as through extensive trade routes further inland to the south.

Aksumite City State (50-150AD)

1st Century AD Aksum

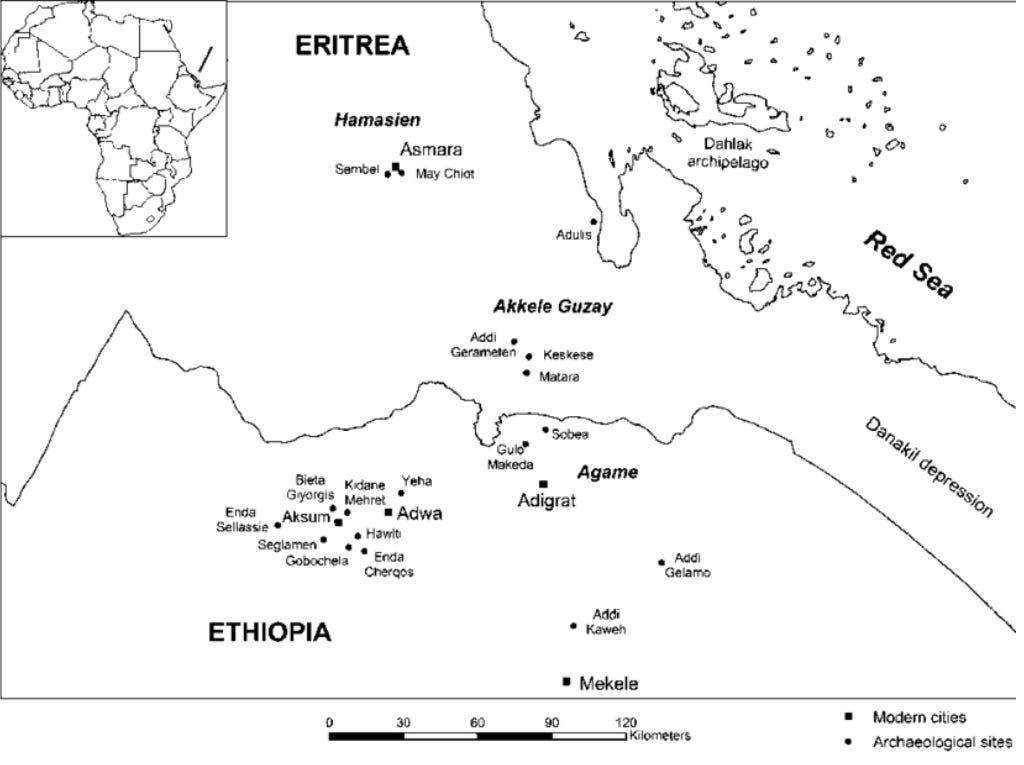

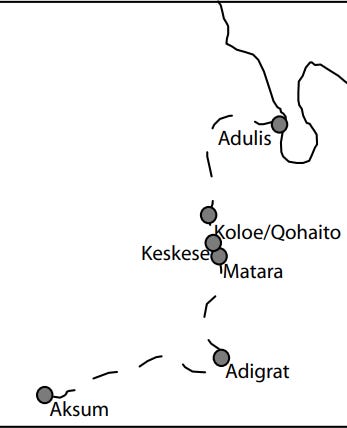

The first recorded mention of the Aksumites appears in the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,” a Greco-Roman text composed between 50 and 100 AD. In this book, Aksum is described as a city distinct from the inhabitants of Adulis, a port village on the Red Sea. This distinction suggests that Aksum was already recognized as a significant political centre at that time, with wealth being accumulated from increased trade passing through Aksum from places further south. The text also mentions Coloe (Qohito), another important town situated between Adulis and Aksum.

Early 2nd Century AD Aksum

The Habesha City State Civil War (~140AD)

Interestingly, the Roman philosopher Aelius Aristides wrote around 144 AD about a war occurring in the Red Sea region, which was likely a reference to a civil war. I theorize that a civil war took place among the Habesha city-states at this time, with participants possibly including Adulis, the Aksumites, and surrounding areas, along with potentially external influences from southern Arabian states like Himyar or Saba. It is very likely that the strength of the Aksumites, bolstered by increased trade, grew to the point where they could exert influence and challenge the preexisting dominion at Adulis. The result of these civil wars was an Aksumite victory, which is evidenced by a royal palace being built at Aksum around 150 AD, as noted in Ptolemy’s Geography.

Palace At Aksum

Later, in the second century AD, the Aksumites are mentioned again in Ptolemy’s “Geography,” written around 150 AD. Ptolemy’s account includes the details of a royal palace located in Aksum, suggesting the existence of a king or a ruling authority in the city at that time. The wealth and power of Aksum were certainly growing during this period, likely already eclipsing other city-states such as Qohioto and Adulis. As trade increased with Rome and southern Arabia, Aksum’s unique inland location provided it with access to vast resources from the surrounding areas, unlike Adulis, which was closer to the coast. It was under these conditions that Negus GDRT’s reign began. However, Aksum did not yet exert direct control over much of the territory that would later become the core of the Aksumite Kingdom.

Evidence of this limited control can be gleaned from Ptolemy’s continued reference to the Adulitae as a separate people, in addition to mentioning Koloe as a separate city geographically close to it. Furthermore, there are no known inscriptions from this period indicating a unified Aksumite rule.

The Birth Of The Aksumite Empire (160-200AD)

Birth Of Emperor GDRT (~160-170AD)

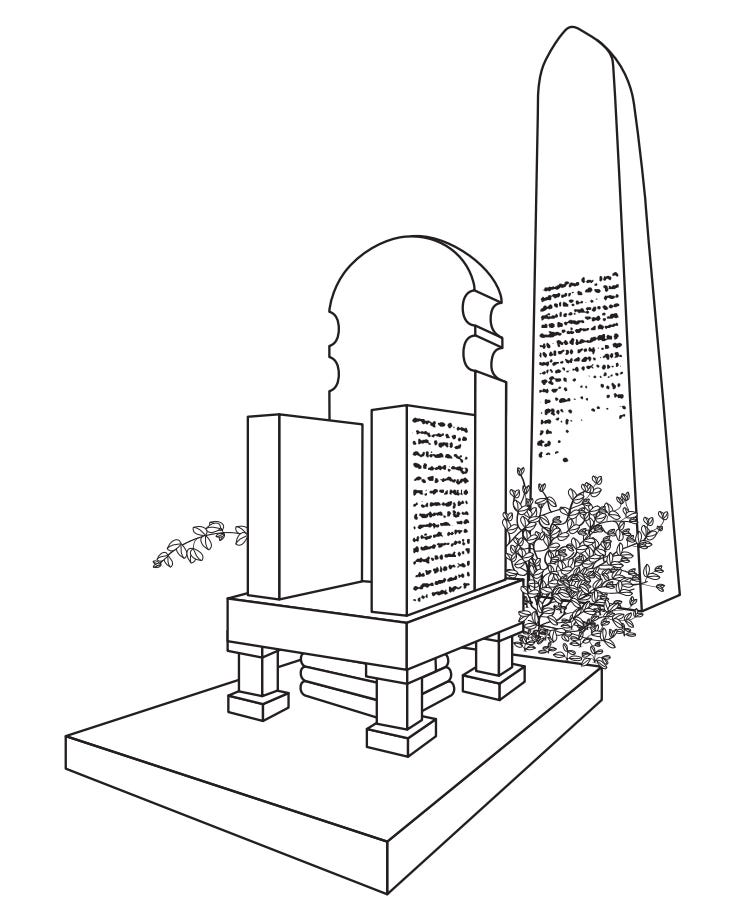

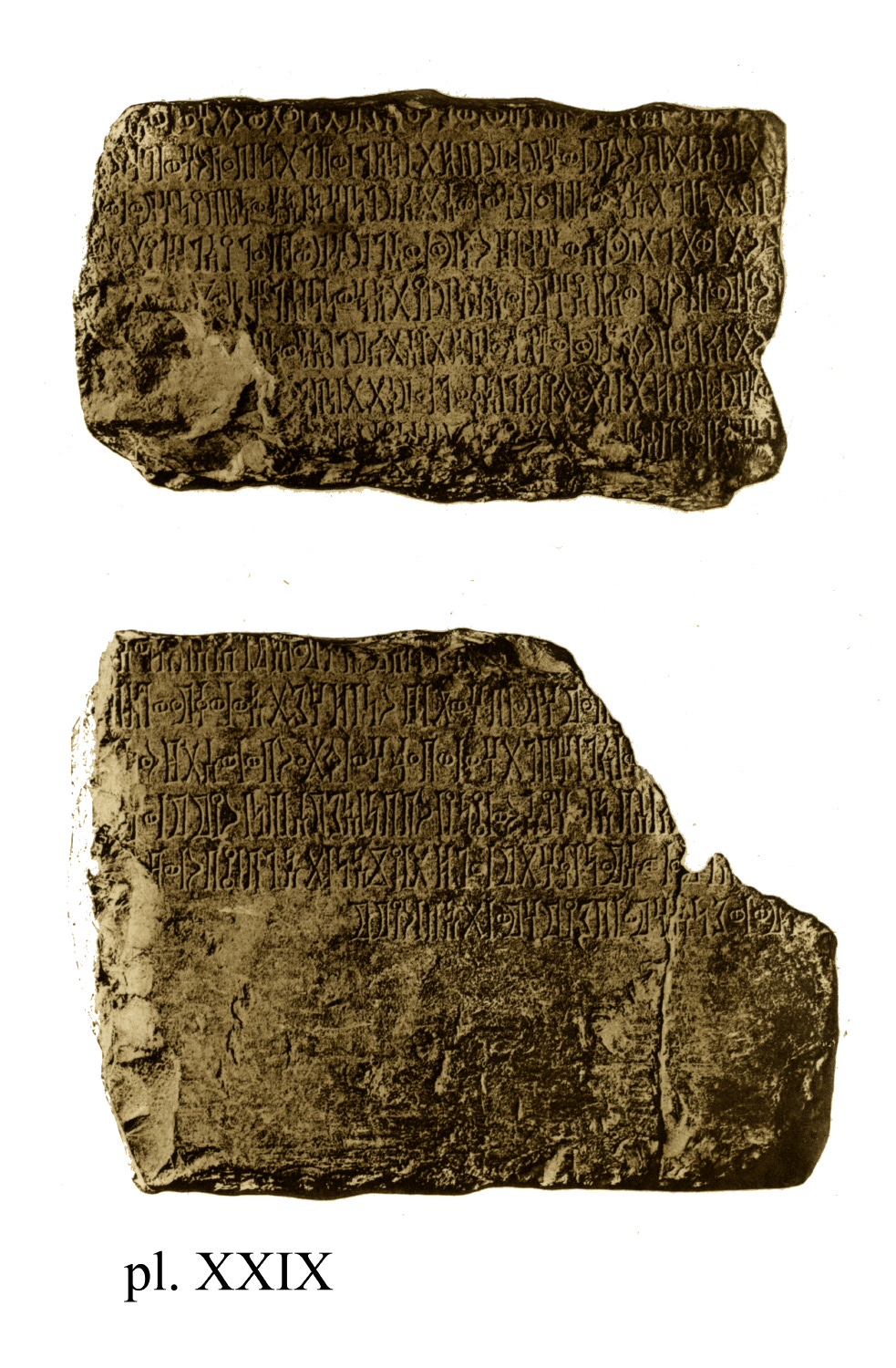

The inscription was originally written on the side of the throne at Adulis, in Greek. By the time Cosmas copied it in the 6th century, the beginning of the stone had broken off and was lost. This missing section likely named the emperor who had conquered these lands, following a common custom in inscriptions throughout the Aksumite Empire. The reason for its removal remains unknown, but one theory suggests a later rebellion by the local populace at Adulis defaced the throne, erasing any mention of the conquering emperor. This theory could also explain why the stele behind the throne had fallen. To this day the Throne or the Stele has not been found at Adulis, however excavation is extremely early in the region.

Somewhere around ~160AD Negusa Negast Gadarat was born, the name GDRT, as found in historical records, is unvocalized, leading to various interpretations and vocalizations by scholars. While the exact vocalization of GDRT in Ge’ez—a classical language of Ethiopia & Eritrea—remains unknown, some possible renditions include Gedur, Gadura, or Gedara2. Despite these possibilities, most scholars today favour the vocalization “Gadarat.” Gadarat is widely considered to be the first king of the Aksumite Empire.

Want more information regarding the structure of the throne? Click here to read more about it

The Throne at Adulis

Description and Historical Context

The reign of GDRT is described indigenously in an inscription on the Throne at Adulis, dated to approximately ~200 AD. This Throne features a Greek inscription on its side that chronicles the conquests of an unnamed emperor. Originally, Cosmas, a Byzantine traveller in the 6th century AD, believed this inscription to be a continuation of the text on a nearby stele. However, modern scholarship has since determined that this is not the case3.

The Greek inscription on the sides of the Throne, and the throne itself, was inspired by the inscription on the Stele which described the historical conquests of the Ptolemaic rulers and Alexander the Great (I have covered this extensively in my article on Adulis). GDRT, wanting to immortalize his achievements in a similar fashion, commissioned this throne with an inscription that detailed his military victories.

The regions mentioned in the inscription are local to Aksum, particularly the initial states that the emperor targeted in his military campaigns.

I theorize that GDRT belonged to a royal family in Aksum that rose to power following the civil war against Adulis in 144 AD. I also think the royal family of the various habesha centres of power were inter-married.

Dating/Authorship of the Inscription On The Adulis Throne

Scholarly Debates on the Inscription’s Date

The exact date of the Greek inscription on the Adulis Throne remains a subject of scholarly debate. Prominent historian Glen Bowersock proposes that the events described in the inscription occurred in the late 2nd century AD or early 3rd century AD4 . I have also concluded that this is the most likely date when the events on the throne occurred, my reasoning is as follows.

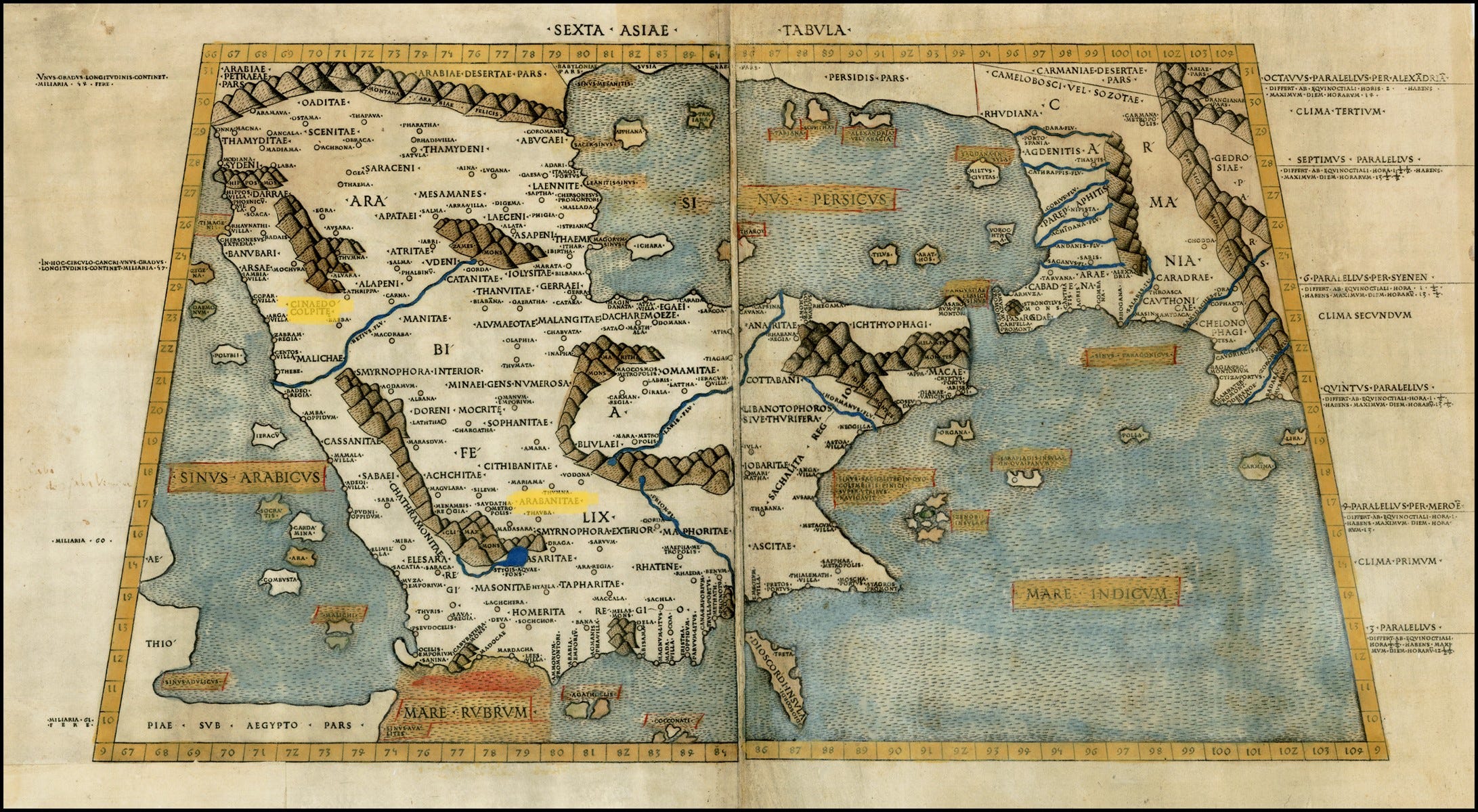

Historical Context of the Kinaidocolpitai

The Kinaidocolpitai are a notable group mentioned exclusively between 150 AD and 300 AD5. This time frame is crucial for dating inscriptions that reference them, as their presence is a significant marker for historians. The Kinaidocolpitai are recorded in various historical documents, including Ptolemy’s “Geography,” but they seem to disappear from records by the mid-third century. This disappearance supports the hypothesis that any inscription mentioning them must have been created during their known period of existence.

Earliest Mentions of Aksumite Emperors

The first recorded mention of an Aksumite Emperor appears in Sabaic inscriptions dating to around 200 AD. These inscriptions are the earliest evidence of the Aksumite Empire’s influence and interactions with South Arabia. The significance of these inscriptions lies in their timing, providing a chronological anchor for other historical events and inscriptions.

I discuss these Sabaic inscriptions near the end of the article….

Excluding Later and Earlier Dates

Mid to late 3rd century AD can be ruled out for the inscription’s creation because it would contradict the claim of being the “first” to conquer lands in Arabia. GDRT’s successors, documented in Sabaean inscriptions, had already established a presence in Arabia by then. A date earlier than 150 AD is also not possible, as earlier texts, including Ptolemy’s “Geography,” clearly differentiate between the inhabitants of the Aksumites and Adulis, indicating that the events described in the inscription could not have occurred before this period. The only Aksumite king attested between 150 AD and before 220 AD is GDRT, leading scholars like Bowersock and others to attribute the inscription to his reign.

The Inscription On The Throne

The Inscription went as follows:

Negus GDRT Initial Conquests

Setting The Stage

Before the rule of the GDRT, the northern highlands likely consisted of various city-states and large chieftains who held dominion over their respective territories. For instance, Adulis was a port city that existed for at least half a millennium, if not longer, during Puntite times. Another significant entity was Yeha, located to the northeast of Aksum, which predates Aksum by several centuries and was an established political centre for a pre-Aksumite civilization known as D’MT. I have covered both of these entities in separate articles. Lastly, Qohaito was another major pre-Aksumite settlement in the region.

GDRT begins his inscription by explaining that he first conquered the nations around him, likely referring to the villages surrounding Aksum, though he does not name them specifically. Securing control over the nearby countryside was crucial before engaging in war with other, more distant Habesha tribes.

The Re-Unification Of Habeshas

The Emperor’s Conquests of Gaze, Agame and Sigyre

Regions and Identifications

Gaze: The region known as Gaze likely corresponds to parts of the area known today as Akele Guzay in modern-day Eritrea. Historical records indicate that the Gaze people inhabited regions just north of Adulis and extended as far south as parts of northeastern Tigray. This strategic location would have made Gaze an important area for any ruler seeking to consolidate power in the region.

Agame: This region is identified as the Agame area in the northern Tigray region of Ethiopia. Agame lies directly below Akele Guzay and has been a significant historical region for centuries. The Agame region was known for its ancient Aksumite and pre-Aksumite sites, marking it as a culturally and historically rich area. The conquest of Agame was essential in unifying Habeshas.

Sigyre: The exact location of Sigyre remains unknown, but it is hypothesized that Sigyre could be an early etymology of the word Seraye. Seraye is a region located to the west of modern-day Akele Guzay and to the northwest of Agame. Seraye has been inhabited by the Habesha people for millennia, and Aksumite artifacts have been discovered throughout the region, supporting this hypothesis.

GDRT’s Strategic Conquests

Upon solidifying his control over Aksum and the surrounding regions, Emperor GDRT embarked on a mission to unite other Habesha city-states. This unification was crucial not only for political and cultural reasons but also for economic purposes. Although Aksum was likely the economic powerhouse of the region due to its significant trade activities, GDRT aimed to expand his access to foreign markets such as Egypt, Rome, India, and Yemen. He also sought to bypass the tariffs and taxes imposed through Adulis, thereby strengthening Aksum’s economic position.

Post-Conquest Implications

The Invasion of Adulis

The first target of GDRT’s expansion was the region around Adulis, inhabited by the Agazians. It’s no coincidence that the Agazians were the first nation he warred with. They were the strongest Habesha tribe after the Aksumites during this era and served as an economic centre second only to Aksum. Additionally, the Agazians held historical significance, likely being the domain of previous rulers such as Zoskales and the site where the historic stelae detailing the conquests of Ptolemy III and Alexander the Great were located.

We will see later on, the importance of Adulis when GDRT returns back at the end of his conquests.

Post-Conquest Implications

After completing these conquests, GDRT claimed to have imposed a tax amounting to half of all the conquered regions’ assets. While this figure may be exaggerated, it is likely that a significant tax was indeed levied on the land, people, and resources. This heavy taxation might explain why the throne at Adulis was later defaced, indicating possible resentment and unrest among the subjugated populations.

Further Conquests: Aua, Tiamo, and Gambela

Locations and Significance

Aua: This location is likely to correspond to modern Adwa, a historically significant town in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. Adwa has been a crucial site in Ethiopian history, particularly known for the Battle of Adwa in 1896, where Ethiopian forces successfully repelled Italian colonizers. In the context of GDRT’s conquests, capturing Adwa would have been a strategic move to control a vital part of the Tigray region.

Tiamo: Also referred to as Tziamo, the exact location of Tiamo is debated among historians. However, it is possible that Tiamo is an early reference to Debre Damo, a mountainous region northwest of Adwa. Debre Damo is renowned for its ancient Aksumite church and monastery. The area has played a significant role throughout Habesha History, and controlling it would have added strategic value to GDRT’s empire due to its unique mountainous terrain, acting as a natural fortress.

Gambela: This region likely refers to areas around Welkait, Kafta Humera in Tigray, and Gash Barka in Eritrea. These regions are inhabited by the Kunama people today. The name Gambela, derived from the Anyuak language meaning “GAM” (to catch) and “BELLA” (tiger), might have been used by the Habesha people to describe the Kunama, Nara, and other Nilotic tribes because of their distinct cultural practices. Not to be confused with the modern Gambela region in southwestern Ethiopia.

GDRT’s Consolidation and Further Conquests

After GDRT successfully conquered the main city-states of the Habesha people, securing vital resources and soldiers to bolster his army, his next objective was to consolidate control over the remaining pockets of Habesha towns. This consolidation was crucial for maintaining the stability and unity of his growing empire. In addition to this GDRT launched his first expedition on foreigners, in this case, Nilotics to the east.

Unidentified Conquests: Zingabene, Angabe & Tiama, Athagaus, and Kalaa

In the third batch of conquests, GDRT mentions five different tribes that he had conquered. The exact locations of these tribes remain unknown to us today. However, by examining the known locations of his previous conquests and his subsequent conquest of the Semien Mountains, we can infer that these tribes were located somewhere south of Aksum but north of the Semien Mountains, likely around the area of modern-day southeastern Tigray.

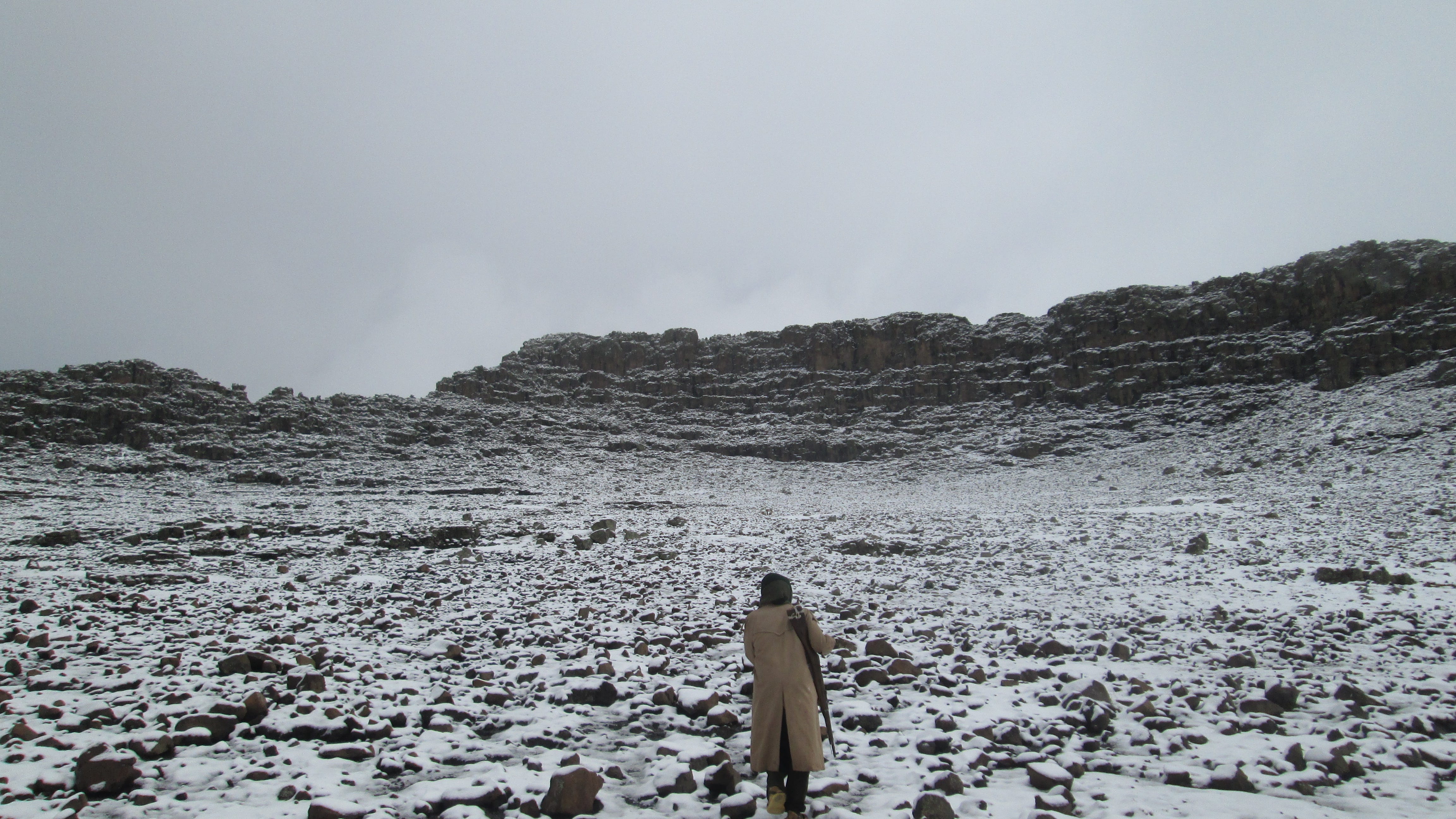

Conquest of the Semenoi

GDRT’s expansion continued further south into Semenoi. The emperor’s description of the Semenoi aligns with the Simien Mountains. He describes them as people living beyond the Nile in mountainous areas that are difficult to access, covered with snow, and experiencing harsh climates with hailstorms, frost, and deep snow. This description unmistakably points to the Simien Mountains, still known for their rugged terrain and severe weather conditions. The mention of the Nile likely refers to the Atbara River, a tributary of the Nile near the Simien region.

It’s interesting to note that even though snow currently occurs in relatively light amounts, during GDRT’s time in the late 2nd century, the climate was much colder. This fact is consistent with the colder climate of the surrounding highland region of that era.

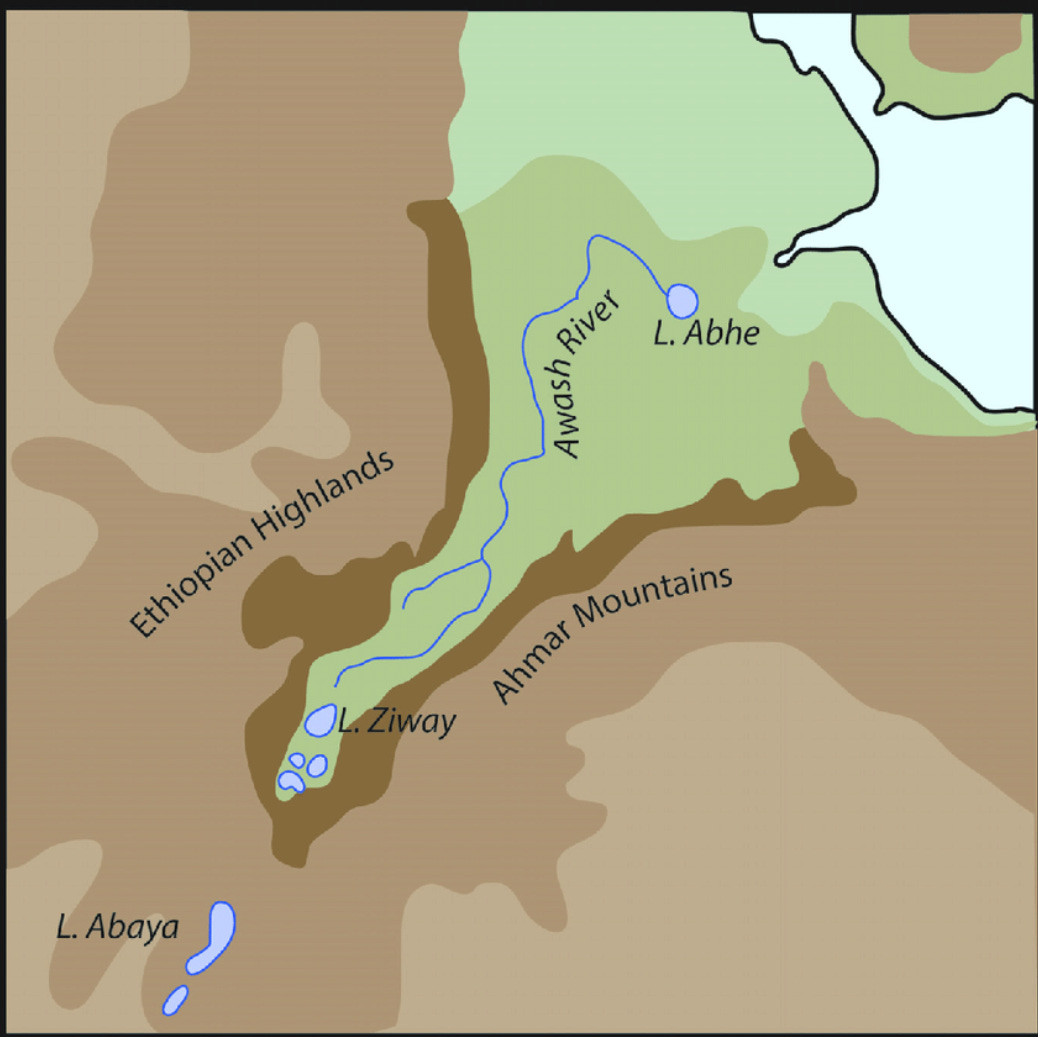

Further Conquests: Lazine, Zaa, and Gabala

After conquering the Semien Mountains, GDRT and his troops likely required rest due to the challenging terrain and battles against the local population. It is plausible that he returned to Aksum to consolidate his previous conquests and resupply his army. From there, he states his next conquests were of the tribes of Lazine, Zaa, and Gabala, who are described as inhabiting mountainous regions with downward slopes and hot springs. This description likely refers to the lowland regions surrounding the Danakil Desert, known for its extreme heat, hot springs, and areas below sea level. These regions are adjacent to the mountainous highlands, suggesting that GDRT led his army from the mountains down into what is now the Afar region, an area still known for its hot springs and one of the harshest climates on Earth.

The conquest of these regions would have provided GDRT with control over strategic lowland areas, ensuring access to important natural resources such as salt, which was also historically used as a form of currency.

Conquest of The North: Atalmo and Bega

After Negus GDRT conquered the Dankali region to the west, he pushed north, moving past Adulis and further into Beja territory.

Identification and Hypotheses

Atalmo: The exact location of Atalmo remains uncertain, but it is speculated to be a tribe situated between the Danakil Desert and the Beja territories, possibly north of Adulis, which would make sense since the Beja are the next group that is specified.

Bega: Identified with the Beja people, this conquest extended the emperor’s influence north of Adulis into what is now Suakin, Sudan.

Conquest of the Tangattae

Geographical Reach

The Tangattae, a powerful Beja tribe, were said to border Egypt6. The emperor’s conquest of the Tangattae suggests that his military campaigns extended as far north as Berenice in Egypt, thereby establishing a land route into Egypt under his control.

This aligns with historical records indicating that the Beja, also known as Troglodytes by Pliny, inhabited regions along the Red Sea, up to Berenice. Bernice was the southernmost port for the Egyptians since the Ptolemaic period.

Implications of the Conquest

Conquering the Beja territories extended the empire’s reach into regions critical for trade routes leading into the heart of Africa and towards the Nile Valley. This expansion facilitated control over caravan routes, increasing the empire’s wealth through trade and tribute. By removing the Beja tribes as intermediaries, the empire could now control trade directly with the Romans, eliminating the need to pay taxes to the Beja tribes for goods passing through their territory.

Strategic Significance

By conquering the Beja tribes, the emperor ensured that the northern borders of his empire were secure and that he had control over strategic routes into Egypt. This not only enhanced his political influence but also opened up additional trade opportunities with the Roman Empire and other civilizations in the northern peripheries.

Conquests of The South

Conquests of Annine and Metine

After GDRT had subdued the various Beja tribes, he likely returned to Aksum & further consolidated his new conquests. His subsequent conquests targeted regions to the south of the Ethiopian/Eritrean highlands, specifically near Somaliland.

First, he conquered the Annine and Metine tribes. Although the exact locations of these tribes are unknown, GDRT mentions that they were situated in the precipitous (steep, with downward slope) mountains, possibly referring to the Ahmar Mountains near present-day Dire Dawa. This speculation is supported by his following conquests of the seaside nations (Barbaria) located in Somalia, which is located directly to the west.

Implications of the Campaigns

The emperor’s campaigns in these mountainous regions extended his control over the southeastern highlands & lowlands, bringing more territory under his influence. This expansion was strategic, positioning the empire closer to the coastal regions of Somalia, which were crucial for controlling trade routes along the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Sasea Conquests: Conquest of Rhausi & Solate

Conquest of the Sesea Nation

The Sesea nation, likely located near modern-day Somaliland and Djibouti, was significant due to its strategic position along the Red Sea. Controlling this region meant dominance over crucial maritime trade routes. The emperor’s siege and subsequent conquest of these tribes, who had hidden in the mountains, resulted in substantial loot and prisoners of war, enhancing the empire’s wealth and labour force. The Seasea may have etymological connections with the Issa clan of Somalia, who inhabit northern Somaliland to this day.

Cosmas kindly annotates that the Sesea nations were in reference to Barbaria.

Conquests in Frankincense Country

- Rhausi Tribes: These tribes lived in waterless plains in the interior of the frankincense country, likely inland areas of Somaliland. Known for their production of frankincense, a valuable commodity in ancient trade, controlling these tribes meant a significant economic gain for the empire and assisted with GDRTs further conquests into Arabia later on.

Return to the Sea: Conquest of Solate

Following his inland campaigns, the emperor returned towards the sea and conquered Solate, likely situated further along the coast of Somaliland.

Tributary States and Voluntary Submission

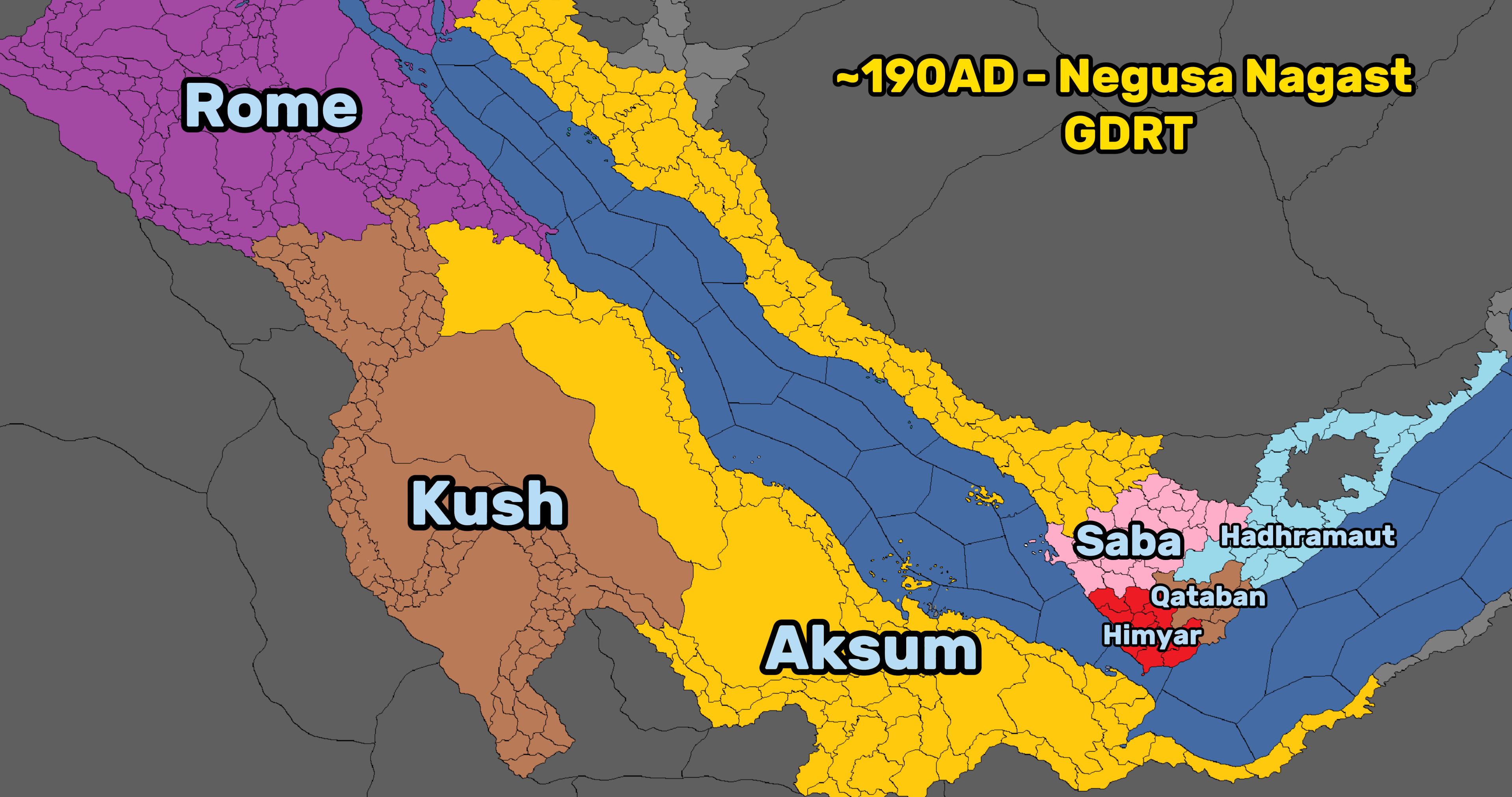

After successfully conquering the lands in Barbaria, GDRT, the Aksumite emperor, took several strategic steps to consolidate his power and expand his empire further. The newly acquired territories provided him with additional resources. such as through taxation and reinforcements for his military forces. With these reinforcements and resources in hand, GDRT returned to Aksum to plan his next major campaign: the conquest of the Arabian states.

Conquests in the Arabian Peninsula

The Strategic Importance of the Arabian Conquest

GDRT’s ambition to conquer the Arabian states was driven by both military and economic motives. The Arabian states were Aksum’s main competitors in the region. Especially in the incense trade. By conquering these states, GDRT aimed to eliminate these competitors and establish Aksum’s dominance both militarily and economically.

Building a Fleet for the Arabian Campaign

To achieve his goal of conquering the Arabian states, GDRT needed to amass a large fleet capable of transporting his army across the Red Sea. The port of Gabaza in Adulis, an essential Aksumite naval base, played a crucial role in this endeavour. Although the Aksumite Empire already had many ships, including those from the recently conquered Barbarian lands, most of these were trading ships. Therefore, additional shipbuilders were required to construct the necessary military vessels.

Time and Resource Management

The construction of the new fleet took time, during which GDRT ensured that his empire’s resources were effectively managed and utilized. Once the fleet was ready, GDRT launched his campaign, beginning from Leuce Kome. Leuce Kome was a historical port of the Nabataean Kingdom, which had been annexed by Emperor Trajan of the Roman Empire and was largely defunct at the time. While GDRT did not conquer Leuce Kome itself, he established control up to this strategic point, thereby creating a direct and unfiltered trade route with Rome.

Conquests in Arabia

GDRT’s conquests in Arabia were systematic and strategic. He first targeted the Kinaidokolpitai, a tribe inhabiting the northeastern Arabian coastline. After subduing them, he moved further south to conquer the Arabitae, another coastal tribe (See the map illustrated previously in the article). His campaigns extended to all lands up to, but not including, the Sabaeans.

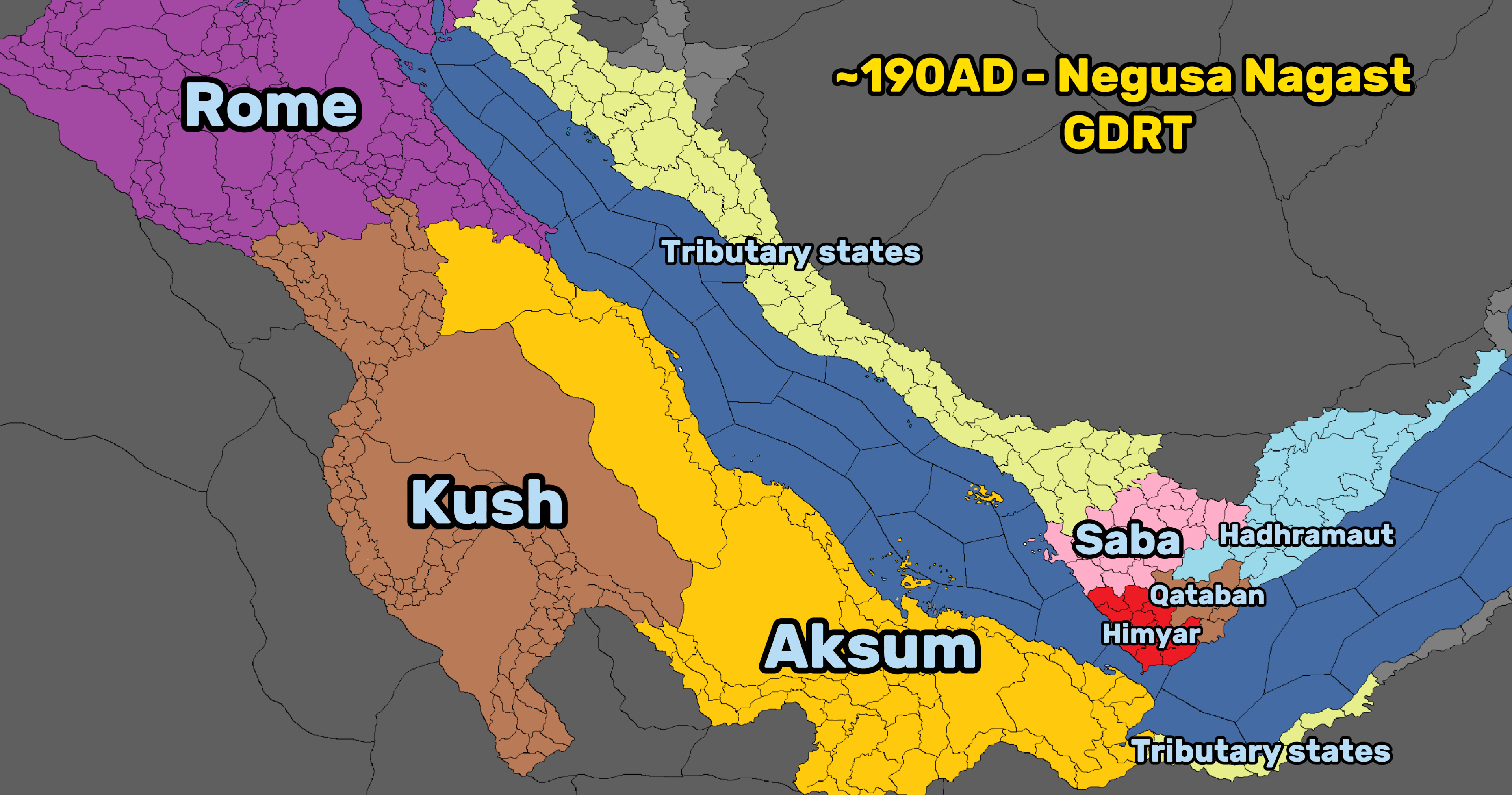

Establishing the Tributary States

These conquests did not imply direct rule over the newly acquired territories as seen in the core of the Aksumite Empire. Instead, these regions became tributary states, required to pay taxes to the Aksumite emperor. This strategy was similar to the previous conquests of the Sesea nations, which also became tributaries. By making these states tributaries, GDRT ensured a steady flow of resources and maintained control over a vast area without the need for direct administrative oversight.

Declaration of Achievements and Gratitude to the Gods

After an extensive campaign of conquest, the emperor successfully dominated regions stretching from Berenice and Leuce Kome in Roman Egypt in the north, to Barberia in the south, and as far west as Sasu. The region of Sasu, noted for its gold mining during the later Aksumite Empire, is likely situated further southwest in Ethiopia, near the Amhara region.

Upon the completion of these conquests, the emperor returned to Adulis, a significant historical site where his ancestors such as Zoskales once ruled. Adulis also housed an ancient stele dedicated to Ptolemy III and the conquests of Alexander the Great. By conquering numerous lands, the emperor mirrored the achievements of these legendary figures. Hence he ordered for a marble Throne to be made right in front of the existing Stele, and on the side of this marble throne he ordered for his conquests to be written in Greek, so travellers from throughout the ancient world would view his conquests when they reached the port city of Adulis.

Proclamation of Success

The emperor proudly proclaimed himself as the first king of his lineage to have achieved such expansive conquests. This declaration was not only a record of his military achievements but also a strategic move to legitimize his rule. By highlighting his military prowess and strategic acumen, the emperor aimed to solidify his authority and command respect from his subjects and allies.

Divine Favor and Military Leadership

Central to the emperor’s narrative was his gratitude to his god Ares, the god of war, whom he credited for his victories. In the local context of Aksum, Ares was known as Mahrem. The emperor’s conquests covered regions to the south and east of Adulis, including the Barbaria states renowned for their production of frankincense, as well as areas west of Ethiopia, such as western Tigray and the Simien Mountains. His leadership was marked by personal involvement in some battles, while in others, he demonstrated his ability to effectively delegate authority to his generals. This balance of direct involvement and strategic delegation underscored his capability as a military leader and ruler.

The emperor’s public expression of gratitude to Ares was a critical element in reinforcing the divine support for his rule and conquests. By attributing his successes to the favour of the gods, he bolstered the legitimacy of his reign. This practice of invoking divine favour was a common strategy among ancient rulers to ensure loyalty and support from their subjects, thereby consolidating their power.

Final Acts

Following his conquests, the emperor returned to Adulis to perform sacrifices to the gods. Zeus, known as Meder by the Aksumites, Ares, and Poseidon (called Behr by the ancient Aksumites) were honoured in these rituals. The emperor believed that Poseidon would bestow good fortune on travellers and merchants journeying by sea from Adulis. In a final act of consolidation, he gathered his army at Adulis and constructed the throne upon which this inscription was written, marking the twenty-seventh year of his reign. This act symbolized the culmination of his conquests and the consolidation of his empire’s power, serving as a lasting testament to his achievements and divine favour.

Post Conquests & The South Arabian Inscriptions Of GDRT

Around 200 AD, significant historical references to the Aksumite ruler GDRT (also known as Gadarat) emerged in South Arabian scripts. These inscriptions provide valuable insights into the conquests and influence of Emperor GDRT during this period, marking a pivotal time in the geopolitical landscape of Southern Arabia.

Geopolitical Landscape of Arabia in the Late 2nd Century

By the end of the second century (~200AD), the Arabian Peninsula was dominated by four major states: Himyar, Saba, Hadhramawt, and Qataban. However, the region was undergoing significant changes:7

- Qataban: Annexed by Hadhramawt between 160 and 210 AD.

- Saba: Engaged in attempts to subjugate Himyar.

Key Rulers of the Period

During this time, the major rulers of the prominent nations were8:

- Aksum: Gadarat

- Saba: Alhan Nahfan

- Himyar: Tharan Ya’ub Yuhan’im

- Hadhramawt: Yada’ub Gaylan

South Arabian Inscriptions and GDRT

The first South Arabian inscription mentioning GDRT dates back to approximately 200 AD and was discovered in Riyām in modern-day Yemen. The inscription was inscribed during the reign of Alhan Nahfan, detailing a treaty with GDRT9.

The inscription reads as follows:

This inscription highlights GDRT presence and actions in the region, signifying the extent of his influence. The inscription reflects a period in the later stages of Gadarat’s conquests, indicating that by this time, he had successfully established a foothold in Arabia and was actively shaping the region’s geopolitics.

Diplomatic Relations Between GDRT and the Sabaean King Alhan Nahfan

From the inscription, we learn that GDRT, (referred to as the Habashite king), had sent a diplomatic delegation to the Sabaean king, Alhan Nahfan. This diplomatic mission aimed to establish both a defensive and aggressive alliance between their kingdoms. The alliance was intended to last for the lifetimes of both kings and beyond. In line 17 of the inscription, it is mentioned that gifts and subventions (monetary support) were exchanged between GDRT and Alhan Nahfan, indicating a strong commitment to their pact.

Geopolitical Locations and Residences

In line 14 of the inscription, there is a reference to “between Silḥīn and Zrrn,” which signifies the territories or residences of the two kings. Silḥīn (vocalized as Salhen) is the name of the palace where King Alhan Nahfan resided, suggesting that Zrrn referred to the palace or residence of King GDRT. This detail highlights the importance of their respective capitals in the diplomatic exchanges.

Line 15 indicates that GDRT had established an alliance with Himyar before forming a new alliance with Saba. GDRT likely leveraged the support of these states during his conquests in the northern Arabian Peninsula.

The First Aksumite War Against Himyar – 220 AD

Key Monarchs

During approximately 220 AD, the following kings ruled over their respective regions10:

- Aksum: GDRT and his son Negus BYGT (vocalized as Baygat).

- Saba: Sha’ir Awtar succeeded Alhan Nahfan after his death around 220 AD.

- Himyar: Li’Azz Yahnuf Yushasdiq.

- Hadramawt: Il’azz Yalut.

Breakdown of Alliances and Regional Shifts

After the death of the Sabaean king Alhan Nahfan around 220 AD, his son Sha’ir Awtar ascended to the throne. The previously strong alliance between Saba and Aksum deteriorated under Sha’ir Awtar’s rule. Subsequently, a new alliance was formed between Sha’ir Awtar and Li’Azz Yahnuf Yushasdiq, the new ruler of Himyar.

The political landscape further shifted with the death of the previous king of Hadramawt, leading to Il’azz Yalut taking the throne. Supported by Sabaean troops, Himyar, under the leadership of Li’Azz Yahnuf Yushasdiq, managed to conquer Hadramawt, significantly altering the balance of power in the region.

Betrayal of Saba and the Rise of Himyar

Following the betrayal by Saba and the rising power of Himyar, which had recently conquered Hadramawt, the geopolitical landscape of the region underwent significant changes. Himyar’s increased economic and political influence became a concern for the Aksumite King Gadarat (GDRT). In response, Gadarat declared war on Himyar. He dispatched his army and a fleet of ships across the Red Sea, with his son BYGT (Vocalized as Baygat) leading the invasion. The Aksumite forces managed to occupy the Himyarite capital, Zafar, demonstrating their military might.

By ~220AD, GDRT was reaching nearly 50/60 years old, assuming he was born ~160AD, therefore it makes sense that his son BYGT led the war and was probably in charge of administrating most of the empire.

However, this conquest was short-lived. The Aksumite forces faced a significant defeat from the combined might of both Saba & Himyarite troops and were eventually forced out of the Himyarite region. Despite this setback, Aksum retained control over areas north of Saba, such as Najran, which they had previously conquered.

The inscription is as follows:

The Passing of GDRT

Around 220 AD, King Gadarat passed away, as this is the last recorded mention of him in any inscriptions. His death marked the end of an era for Aksum and led to new challenges and changes in leadership, which I’ll explore in my subsequent articles.

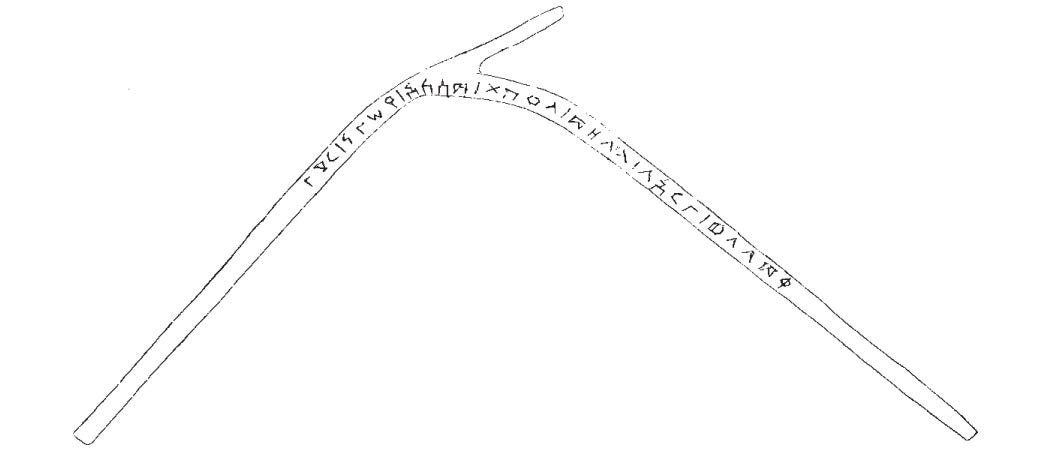

GDRT’s Sceptre

Unfortunately, besides the throne in Adulis and the Sabaean inscriptions, only one other inscription has been found relating to GDRT, on an object that might have been wielded by GDRT. This indigenous copper alloy object includes an inscription stating “GDR NGSY KSM,” which is the unvocalized version of Gadarat, Negus (of) Aksum. This inscription has been dated to around 200 AD11.

Conclusion

GDRT was not only an emperor but also a conqueror, administrator, and strategist. During his reign, he transformed from a petty city-state king of Aksum into an emperor whose influence extended to the borders of Roman Egypt, spanning two continents. Over land and sea, he conquered more than a dozen nations in the Horn of Africa and Arabia. He engaged in the politics of the southern Arabian kingdoms of Saba and Himyar, culminating in an invasion of Himyar. Although this invasion ultimately failed, his legacy endured for centuries, inspiring Emperor Kaleb in the 6th century AD to successfully conquer Himyar.

GDRT, King of Kings, arrived in Adulis when it was a city of stone and left it with a throne of marble.

Sources

In terms of sources, I used a wide range of them. I primarily used primary sources, however, I also read the following books:

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam

- Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC-AD 1300

- Reconsidering Yeha, c. 800–400 BC by Rodolfo Fattovich, pg, 276 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 71 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 20 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 56 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 56 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, pg 51 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 72 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 72 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 72 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 72 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 79 ↩︎