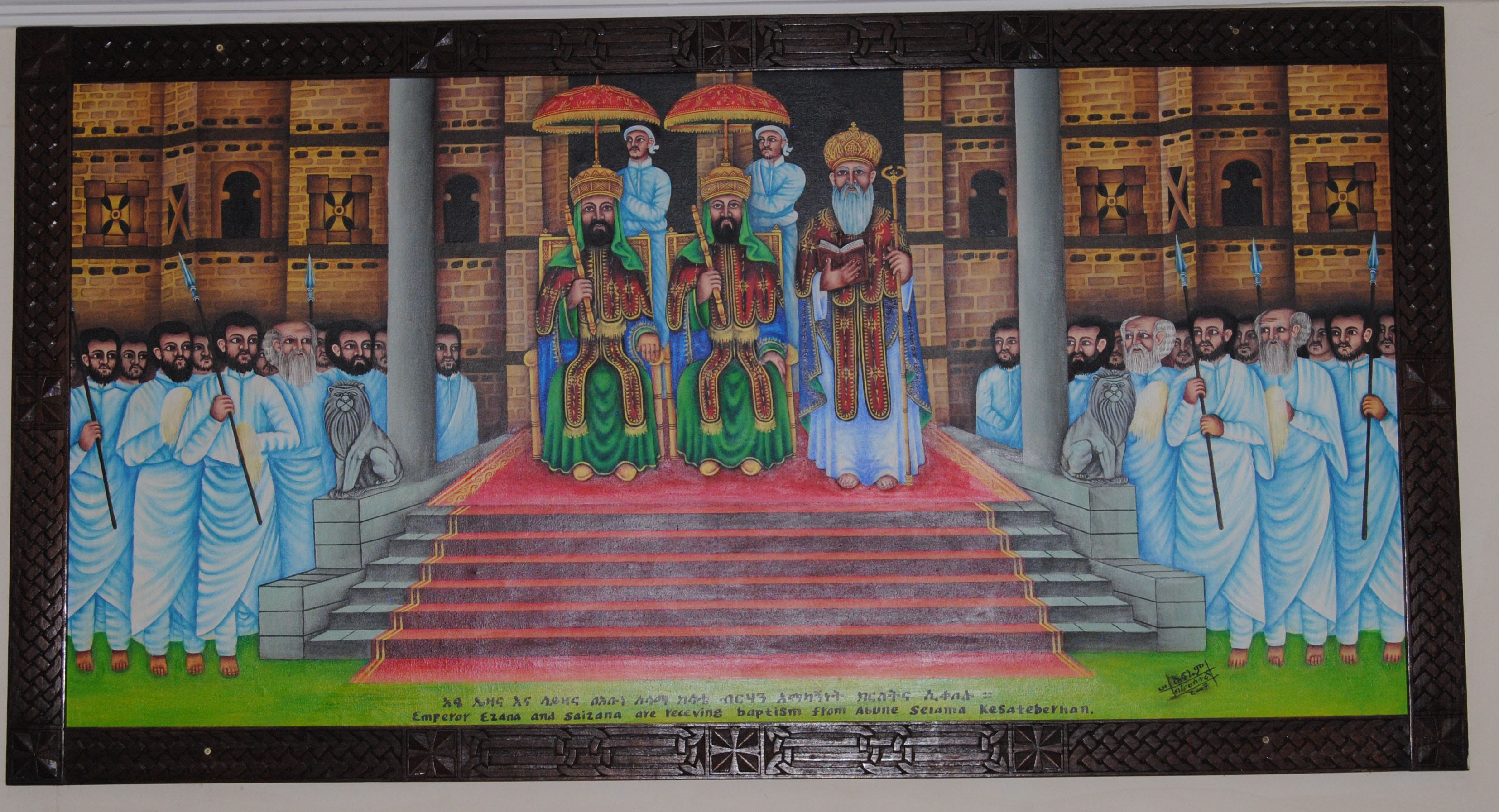

Ezana and Saizana: Two Brothers, Two Emperors, Two Saints. They Crushed Rebellions Throughout The Empire & Officially Converted the Aksumite Empire to Christianity In The 4th Century AD.

Abune/Abuna means “Our Father” in Ge’ez, and is used in reference to the bishops of the Ethiopian & Eritrean Orthodox churchs.

Loading the Elevenlabs Text to Speech AudioNative Player...

Introduction

Around 320 AD, Emperor Ezana & Saizana ascended to the throne and are now remembered as one of three Aksumite emperors who became saints. Ezana is the second most well-known emperor of the Aksumite Empire, surpassed only by Emperor Kaleb. Unfortunately, Ezana’s father passed away during his childhood, leaving both him and his twin brother Saizana too young to rule. For several years, their mother, Queen Regent Sophia, governed with the support of various court advisors from across the Empire.

Among these advisors were Frumentius and Aedeius, two young men who had been captured and raised by Ezana’s father, Ousanos. (For more information, check out my previous article). These two had tutored Ezana throughout his childhood, undoubtedly influencing his character. By the time Ezana became a teenager, both Frumentius and Aedeius had become highly respected court officials, with Aedeius serving as a cupbearer and Frumentius as the treasurer and advisor to the Queen Regent. They also introduced the royal family to Orthodox Christianity. Traditional accounts suggest that Ousanos and Queen Sophia had converted to Christianity1.

During this period of religious transition within the Aksumite region, particularly within the royal family, the empire faced considerable unrest. The large territories in Nubia, conquered by Ousanos and likely still harbouring dissent, coupled with his untimely death, left the empire in a precarious state. Rebellions were brewing. In the first decade of Ezana’s rule, he focused on quelling these uprisings in the north and south of his empire. After stabilizing the region, Ezana officially declared Orthodox Christianity as the state religion and replaced the crescent and sun symbol on Aksumite coinage with the cross, making Aksum the first nation in history to mint coins bearing the cross. Lastly, he suppressed a rebellion, located in the newly conquered Nubian territories.

Childhood Of Ezana & Saizana (~300AD-~320AD)

Around 300 AD, Emperor Ezana was born. While the exact date of his birth is unknown, it can be estimated based on his reign, which began around 320 AD. Assuming he was between 16 and 20 years old when he ascended the throne, a birthdate around 300 AD seems reasonable. Queen Sophia gave birth to twins, one named Ezana and the other Sazanna, followed by at least one younger brother. Our knowledge about Ezana’s birth and early childhood comes from a traditional account in a manuscript called Gedle Abreha and Asbeha, purportedly first written by Frumentius himself, and copied numerous times ever since, with one of the latest copies located in Abra We Astbeha church in Tigray Ethiopia.

The scholar Sergew Hable Selassie translated important excerpts from this manuscript, as follows:

Family Structure and Early Life

From lines 1-3, we can deduce the family structure of the Aksumite royal family during this time. Tazena most likely refers to Ella-Amida, also known as Ousanos in Aksumite coinage. Their mother was Sophia, and Ezana and Saizana were twin boys.

Fertility Issues and Political Repercussions

Lines 4-5 suggest that Queen Sophia experienced fertility problems, leading to succession issues and revolts. Although the claim about her fertility problems cannot be confirmed with certainty, we do know that multiple rebellions broke out during the reigns of Ousanos and especially Ezana. This period was marked by significant instability, which could have been exacerbated by uncertainties regarding succession.

Religious Influence and Early Protection

In lines 6-8, it is claimed that the twin brothers were baptized as Christians. While there is no concrete evidence that either was Christian before he publicly declared the conversion of the Aksumite Empire at ~340 AD, we know that Frumentius, a key religious figure, was close to both the queen and the king. If the royal family had converted to Christianity, it is plausible that they would have baptized their sons. The text also mentions that the twins were placed in a temple in Aksum for protection. Although this cannot be confirmed, it is plausible that protective measures were taken due to the political instability and potential threats from malicious actors.

The text also reveals another name for Queen Sophia, Ahiyewa, who ruled for three years. This would suggest that Ezana and Sazanna were already teenagers by the time their father died. However, the account by Rufinus, a Roman philosopher and historian, mentions that the boys were just infants when the king died, indicating some discrepancies in the dating of these events. Both accounts refer to a regency taking place, so if anything that fact can be established.

Speculative Political Dynamics

Lines 9-13 enter more speculative territory, highlighting the lack of unison among the priests and the people within the Aksumite Empire during this period of change. Despite the uncertainties, it is established that Ezana and Saizana were co-rulers for at least part of Ezana’s reign. A letter from the Roman Emperor Constantine I addresses both Ezana and Saizana by name, supporting the notion of dual rulership. As twin brothers, sharing power might have been a strategic decision to prevent civil war and ensure stability. We will see later on that Saizana would play a more militarist role while Ezana assumed an administrative one.

The Beja Rebellion (~320-330AD)

Early in the rule of Emperor Ezana, a significant rebellion erupted in the Beja territories, located in modern-day northeastern Sudan. The Beja people have inhabited these lands since early Greco-Roman times in the 1st millennium BC, if not earlier. By the 1st century AD, Emperor Zoskales ruled over these lands, and in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, Emperor Gadarat of Aksum and his successors also conquered and held dominion over these regions.

The exact reasons behind the Beja tribes’ rebellion during Emperor Ezana’s time remain unclear. However, it is highly likely that the collapse of the Kushite Empire at Meroe, at the hands of Ezana’s father, contributed to increased instability in the northern periphery. The Kushitic Kingdom had played a crucial role in maintaining law and order, especially in the northwestern parts of the Beja territories bordering Kush. The Beja, known as nomadic warriors, probably began pillaging trade routes between Aksum and Egypt due to the lack of authority in the north2. These activities likely escalated into open rebellion, prompting Ezana to respond.

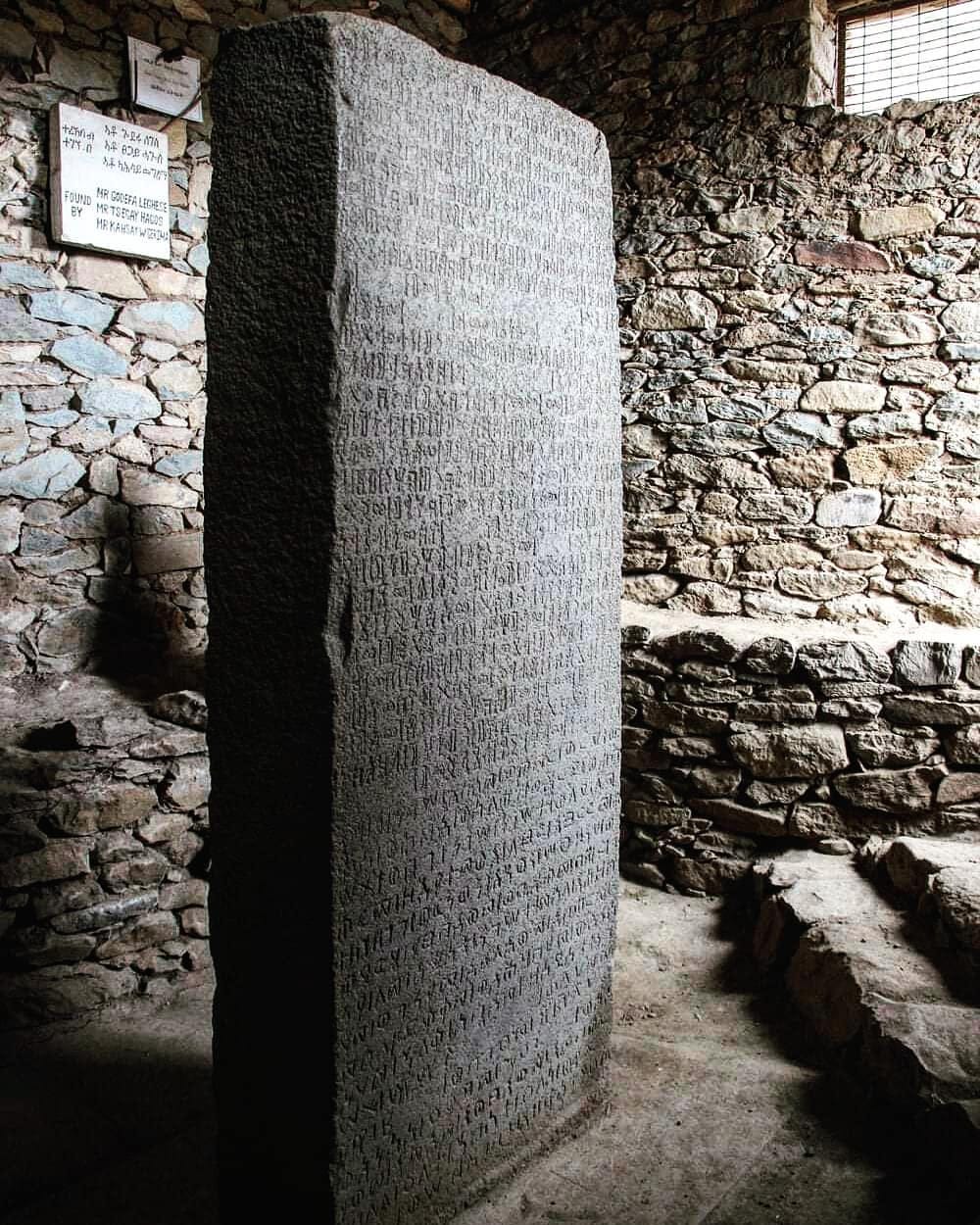

The details of these events are explained in various inscriptions found at Aksum, with the most famous being the Ezana stone, pictured above. According to the inscriptions, Ezana dispatched an expedition to quell the rebellion and restore order. His twin brother Saizana and younger brother Hadefan served as generals during this campaign.

This rebellion occurred early in his reign, we know this because the inscription mentions pagan gods, which he stopped mentioning in inscriptions after his conversion to Christianity.

In the Ge’ez version lines 11-16 mention indigenous variations of the greek gods, Astar(Zeus), Behr (Poseidon), Mahram (Ares). In addition to this an additional paragraph follows: “And as we have erected (this stele), let it be propitious for us and for our country forever. And we have offered to Mahrem a SWT and a BDH”3.

Analysis

Titles and Territories

Emperor Ezana of the Aksumite Empire, styled himself with grand titles. He referred to himself as the “King of the Aksumites, Himyarites, Raeidan, Ethiopians, Sabaeans, Silei, Tiamo, Beja, and Kasu,” along with the grandiose title of “King of Kings” and claimed to be the “Son of the God Ares.” This self-styling highlights his ambition and the perceived extent of his influence.

“Aksumites” represented the core of his region, centred around Aksum and the highlands where predominantly the Habeshas lived, while Ethiopians was a catch-all phrase for the larger area outside of the core, further north, south, east and west.

Doubts About His Rule in Arabia

However, historical evidence casts doubt on Ezana’s actual control over some of these regions, particularly in Arabia. No contemporary South Arabian inscriptions corroborate his rule over Himyarites, Raeidan, or Sabaeans during his time. This discrepancy suggests that his claims might have been more aspirational or propagandistic rather than reflective of actual political dominance4.

Uncertain Territories: Silei and Tiamo

The exact location of Silei remains unknown to historians, and the identification of Tiamo is also ambiguous. Tiamo might be in reference to Debra Damo, but this is just a guess.

The Kasu and Beja Tribes

The Kasu are identified as Kushitic tribes that were part of the former Kushite Empire5. The Beja tribes, located in the region of modern-day Sudan and Eritrea, inhabited the region for over a millennia and were under Aksumite jurisdiction for more than a century at this point.

Military Campaigns and Conquests

Rebellion of the Beja Tribes

When the Beja tribes rebelled against Aksumite authority, Ezana dispatched his twin brother, Saizana and his younger brother Adiphan, to quell the uprising. The military campaign was successful, resulting in the defeat of the Beja tribes.

Was Saizana still a dual emperor at this time, or was he demoted to a general? We don’t know, but the inscriptions only mention Ezana as the ruler. This might suggest that the dual rulership system was quickly removed, with Ezana becoming the sole ruler while Saizana maintained a high status as a general.

Aftermath of the Campaign

Following the victory, there was a significant displacement of the Beja tribes. According to records, 3,112 cattle, 6,224 sheep, and 677 beasts of burden (likely donkeys and horses) were relocated from their original habitats to Matlia (location unknown). Ezana claims that during this displacement, the inhabitants were provided with food and drink. The displacement and the allocation of resources indicate a systematic approach to consolidating Aksumite control over the conquered tribes.

Distribution of Resources

Ezana mentioned that each of the six kinglets of the Beja tribes received 4,190 cows. This distribution of livestock was possibly a strategic move to secure loyalty and establish control over the subjugated tribes.

Religious Dedications and Propaganda

Dedication to the Gods

Ezana dedicated his military victory to various deities, primarily to Ares, the god of war. He also paid homage to the gods of earth and heaven. In honour of his triumph, statues made of gold, silver, and bronze were crafted, symbolizing both religious devotion and the grandeur of his reign.

The Ge’ez Stele Inscription

In the Ge’ez version of his inscriptions, it is claimed that the stele commemorating his victory would bring prosperity to the Aksumite Empire. This assertion underscores the role of religious and cultural propaganda in legitimizing his rule and projecting his power, these stele which we see around not only the highlands of Eritrea & Ethiopia but also further south, pre-date the Aksumite Empire however their use as symbols of power is clear from this inscription.

The Agaw Rebellion in the South (~320-330AD)

During Ezana’s reign, an inscription mentions an interaction Emperor Ezana had with the king of the “Agwezat,” which most likely refers to the Agaw people who inhabited the southwest region of Aksum near Lasta. This battle provides important information regarding the armies he used, which were organized into different legion-like structures. The Muhazat were the commandos, the Dakuen were the elephant fighters, and the Hara were the infantry6.

The inscription was written in Ge’eez & reads as follows:

Analysis

The inscription begins by detailing his claimed titles and the regions under his dominion. These titles highlight his power and the extensive reach of his empire. The narrative then shifts to the activities of the Agaws.

Tribute from the Agews

The Agaws, led by their king Aba’alkeo, initially travelled to Angabo to pay tribute to Emperor Ezana. This tribute included camels, donkeys or horses, food, and possibly men and women. The smooth proceedings of this initial tribute-gathering ceremony suggest a semblance of loyalty and submission to Ezana’s authority, at least prior to the rebellion.

Discovery of Aba’alkeo’s Betrayal

However, the situation changed dramatically by the third day. It was then that the perfidy, or betrayal, of King Aba’alkeo was discovered. Perfidy, in this context, implies disloyalty and deception. This sudden revelation raises questions about the timing and prior knowledge of the emperor. It is plausible that Emperor Ezana orchestrated the tribute-gathering as a strategic move to safely position his army within Agew territory, thereby allowing him to suppress any rebellious forces swiftly and without the onset of a larger civil war.

Capture and Humiliation of Aba’alkeo

Following the revelation of Aba’alkeo’s betrayal, Ezana’s forces took decisive action. The town was pillaged, and Aba’alkeo was captured and humiliated by being chained to his throne naked, a significant act meant to embarrass and demoralize. Thrones, symbols of power, were common across Aksum, including in Adulis, and it is reasonable to assume that the Agaw king possessed his own throne.

Rebellions and Military Campaigns

The capture of their king led to uprisings among the Agaws. Emperor Ezana’s forces, notably the armies named Mahaza and Metin, engaged in battles against the Agaw rebels. These forces looted towns such as Asala, Ereg, and Agada. Another army, Dakan, attacked the Agew town of Se’ezot.

Military Reorganization and Further Attacks

After reorganizing and resupplying, including provisions such as water, the armies continued their campaigns. The armies named Daken, Hara, and Metin consolidated their forces at Adyabo. Subsequently, the Hara army attacked the town of Zawa. Finally, the Laken army was dispatched against the towns of Hasabom, Tuteho, Lawa, Asyam andHezaba, where they established a camp before attacking the town of Magaro.

Unfortunately we don’t know the specific locations in the Agaw territory, however considering the mention of several different towns throughout the war, it probably spanned a large territory in modern-day Wag & Lasta in Ethiopia and probably periphery regions…

Ezana’s Conquest Of The Afan (~320-330AD)

Another inscription dating early into the reign of Emperor Ezana before his conversion to Christianity, mentions an expedition into Afan territory. We do not know the location of the Afan but historian Sir E. A. Wallis Budge theorizes it was at the very south of the Aksumite empire, to the point where they didn’t exert much or any direct control7. The events of the inscriptions occur because, as Ezana claims, a merchant caravan passing through the region was attacked by the local inhabitants.

The inscription reads as follows:

Analysis

Introduction to Emperor Ezana’s Titles

The initial passages in the historical records re-emphasize the various titles held by Emperor Ezana, underscoring his paramount status and authority in the Aksumite Empire.

War Against the Sarane People

The account proceeds to describe a military campaign waged against the Sarane people, who resided within the Afan Kingdom. The catalyst for this conflict was the murder of a merchant and his aides by the Sarane people while they were traversing through their territory.

Deployment of Elite Regiments

Emperor Ezana deployed three of his armies, named Mahaza and Dakuen and Hara, to address the situation. These forces are notable because they had previously been engaged in battles against the Agaws, suggesting that they were elite regiments with significant combat experience. The three armies convened at Alaha, a region friendly towards the emperor, before setting off towards Sa’ne in the Afan Kingdom.

Confrontation and Outcome

Upon arrival, the emperor’s forces encountered several tribes including Sawante, Gema, and Zahtan. During the ensuing conflict, a person named Atila and his children were captured. Although the identity of Atila is not definitively known, it is likely that he was either the king of the Afan or held a position of significant authority within the kingdom.

The campaign resulted in a decisive victory for Emperor Ezana. Records state that over 700 individuals were killed, and more than 300 prisoners were taken. Additionally, the emperor’s forces seized substantial amounts of booty, including over 30,000 cattle and more than 800 donkeys and horses.

Return to Aksum and Celebration

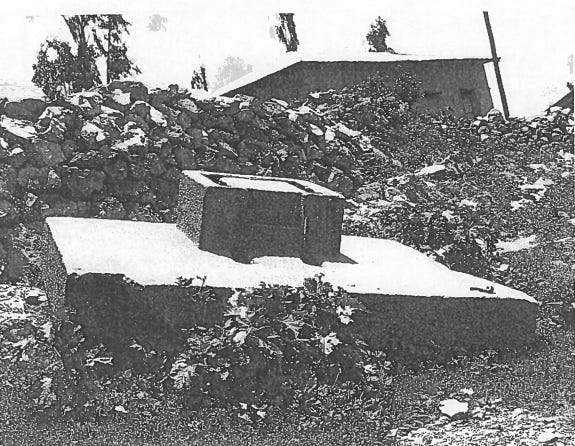

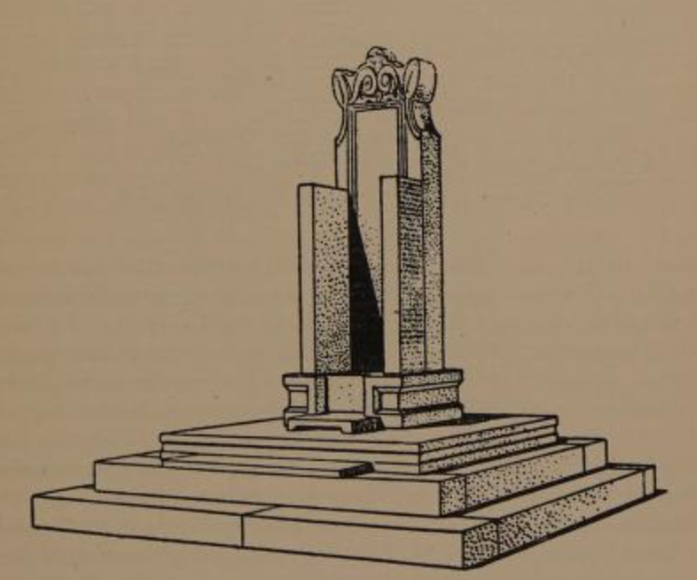

Following the successful campaign, Emperor Ezana returned safely to Aksum. He commemorated his victory by establishing a celebratory throne at Shado (possibly a village in Aksum).

Religious Tributes and Warnings

The concluding passages of the records express tributes to the gods, acknowledging their favour and support. Furthermore, a stern warning is issued to any potential rebels, emphasizing that any future insurrections would be swiftly and decisively crushed.

The Aksumite Empire’s Official Adoption Of Christianity (~330AD-340AD)

Between 330 and 340 AD, Emperor Ezana and his brother Saizana officially established Christianity as the state religion of the Aksumite Empire. This conclusion is supported by the fact that around 343 AD, Constantius II, the son and successor of Emperor Constantine the Great, assumed power in the Eastern Roman Empire. As noted in historical records (the next section will go through this in detail), it was Emperor Constantine I not II who corresponded with the Aksumite emperors regarding Frumentius, the bishop of the Aksumites. Therefore the conversion couldn’t have happened after 343 AD.

Furthermore, this period marks a significant change in Aksumite coinage, with the transition from the pagan sun and crescent symbol to the Christian cross. Coins minted with the cross under Ezana’s reign highlight the Aksumite Empire as the first nation in history to produce coinage bearing the cross symbol.

Emperor Constantine The Great’s Letter To Ezana & Sazenna

Early in the reign of Emperor Ezana and his brother Sazana, around 320-330 AD, the Aksumite Empire was under dual rule. Simultaneously, up north, Constantine the Great had recently become emperor of the Roman Empire and was implementing significant changes. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, his promotion of the faith throughout Roman society, and the establishment of Constantinople as the new capital were transformative events.

Constantine adhered to Arianism, a belief among some early Christians that Jesus Christ was a created being, by God, thus implying a distinction between God, who is uncreated, and Jesus Christ, who was created. This theological stance caused considerable division within the early Christian community. Athanasius, the Archbishop of Alexandria, opposed Arianism and had consecrated Frumentius as a bishop. This opposition brought Athanasius into conflict with Emperor Constantine, leading to his replacement by George of Cappadocia, who was sympathetic to Arianism8.

The appointment of Frumentius as bishop by the ousted Athanasius posed a problem for Constantine. In response, the emperor sent envoys to the Aksumites to have Frumentius re-examined theologically in Alexandria. The Aksumites refused, prompting Emperor Constantine to send the following letter:

It’s unlikely that the Aksumites handed Frumentius over to the Romans, and the letter was most likely ignored. Traditional accounts testify that Frumentius died within the Aksumite Empire. Moreover, Frumentius is venerated as a saint, and the church to this day does not support Arianism.

Ezana’s Wars Against The Rebellious Kushites & Nubians (~340-350AD)

The final military campaign inscribed by Ezana is notable for its size and uniqueness. Unlike previous campaigns, which credited pagan gods for successes, this one attributes victory to a singular God, referencing the Christian deity. This aligns with the Aksumight Empire’s official adoption of Christianity, symbolized by the cross on its coinage in 335 AD. The inscription details the war against the inhabitants of the former Meroitic kingdoms, specifically the Noba (Nubians) and the Kasu (Kushites).

During the late 3rd century AD, under Emperor Diocletian’s reign, the Romans resettled the Nobatai, likely a northern Nubian group originally from the western Desert region of Egypt (the southern west periphery of Egypt, part of the Sahara). The Nobatai were relocated to the border area between southern Egypt and the territories of the Blemmyes and Kushites, known by ancient Greco-Romans as the Dodekaschoinos. This strategic resettlement aimed to use the Nobatai as a buffer against the Beja tribes, who were frequently disrupting Roman trade routes during this period9.

The following is a translation of the inscription, originally in Ge’ez:

This inscription is also the first Ge’ez text found to be entirely vocalized10

Analysis

Introduction and Religious Invocation

King Ezana of Aksum begins his inscription with a reverent acknowledgment of the Lord of Heaven, emphasizing the supreme power and central importance of Christianity in his reign. This invocation sets the tone for the document, underlining that all his actions and successes are attributed to divine will and support.

Titles and Tribal Affiliation

Following the invocation, Ezana lists his titles and his tribal affiliation with Halen.

Justification for War Against the Noba

Ezana reiterates his praise for the Lord of Heaven before recounting the declaration of war against the Noba people. This war is portrayed as a response to rebellions and insults directed at the Aksumites. The Noba had mocked the Aksumites, claiming they would never cross the Takaze River, a tributary between modern-day Sudan and the Ethiopia/Eritrea region. Furthermore, the Noba had repeatedly attacked the Mangurto, Khasa, and Barya tribes. While the identities of Mangurto and Khasa remain unclear, the Barya are recognized as the Nara, who inhabit southwestern Eritrea today.

Differentiation of Ethnic Groups

Ezana notes that the Noba attacked both “blacks” and “reds,” likely referring to Nilotic peoples and Kushites/Semitized Kushites, respectively. This distinction underscores the diverse ethnic landscape of the region and the broad impact of Noba aggression.

Breach of Oaths and Envoys’ Mistreatment

The Noba had violated their oaths to the emperor by attacking their neighbours, exacerbating the situation. When Aksumite envoys were sent to investigate complaints about the Noba, they were harassed, looted, and killed. This blatant disregard for diplomatic protocol further justified Ezana’s military response.

This gives us further insight into the diplomatic strategy utilized by the Aksumites, prior to wars & rebellions, the Aksumites would use diplomatic means through the use of envoys with the opposing side.

Military Campaign and Victory

Ezana describes how he led his army to the Takaze and the fort of Kemalke. The victory was swift, with the defenders fleeing, prompting Ezana to pursue them for 23 days. The campaign resulted in prisoners being taken, and substantial looting of copper, food, iron statues, and treasures. Executions took place along the Nile’s tributary (Atbarah River), and Aksumite soldiers also raided and sank Noba boats.

Capture of Noba Chiefs

The capture of two Noba chiefs, Yesaka and Butale, who were acting as spies, is highlighted. Additionally, more than five chiefs were killed in battles. Ezana’s campaign extended north, where he fought the Kasu people in the former Meroitic kingdom region. His army, composed of Mahaza, Hara, Damawa, Falha, and Sera, attacked cities like Awla and Daro, resulting in more looting, prisoners taken, and deaths.

Establishment of Control and Loot

Ezana claims to have set up a throne in the conquered Kushitic region, symbolizing his authority. He reports capturing over 600 people, killing 700, and looting over 60,000 animals.

Conclusion and Warning

Ezana concludes by thanking the Lord of Heaven for the victory and issues a warning to potential rebels. The throne he mentions represents not only a seat of power but also the Aksumite right to authority.

The defacement of many such thrones since the aksumite period, suggests subsequent rebellions by local inhabitants or foreign powers targeted these symbols of power.

Legacy of Ezana and Saizana

Influence on Aksumite and Habesha History

Emperor Ezana and Saizana were pivotal figures whose reigns significantly altered the trajectory of the Aksumite Empire and the broader Habesha region. Their most notable achievement was the official adoption of Christianity, a decision that fundamentally shaped the cultural and religious identity of the Habesha people and other peripheral groups in the region. This momentous shift in religious alignment not only redefined the internal dynamics of the Aksumite Empire but also influenced subsequent historical developments for over two millennia.

Under the reign of Ezana and Saizana, Christianity became the state religion, facilitating its spread throughout the empire. This change was embraced by future Aksumite rulers, culminating in the reign of Emperor Kaleb in the 6th century AD. Emperor Kaleb’s campaign against the Himyarite Kingdom, motivated by the persecution of Christians, is often viewed as a pseudo-holy war, demonstrating the deep entrenchment of Christian values in Aksumite politics and society.

Even after the fall of the Aksumite Empire, Christianity remained a central element in the region’s identity and governance. The Zagwe dynasty, which rose to power around the 11th-12th centuries, continued this tradition from their base in Lasta. The dynasty’s adherence to Christianity is exemplified by Emperor Lalibela’s renowned rock-hewn churches, which stand as a testament to the enduring legacy of Christian faith.

The Solomonic dynasty, which succeeded the Zagwe, further entrenched Christianity in the political and cultural life of the region. Ruling for another 700 years, the Solomonic emperors oversaw numerous religious wars, including the notable Gragn Wars, fought to defend and propagate their faith. This era also saw the construction of numerous churches and the solidification of Orthodox Christianity in the daily lives of the Habesha people, influencing their dress, diet (notably fasting practices), and music.

Canonization and Legacy

Due to their substantial contributions to the consolidation of the Aksumite Empire, the suppression of rebellions, and their pivotal role in the adoption of Christianity, both Ezana and Saizana are revered as saints in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Their legacies are honoured and remembered for setting the foundation that allowed Christianity to flourish and shape the region’s identity.

Sources, Q/A, Improvements and Suggestions

Bibliography

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 93 ↩︎

- History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia, pg 244 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 224 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 79 ↩︎

- History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia, pg 249 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 95 ↩︎

- History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia, pg 247 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 100 ↩︎

- The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, 71 ↩︎

- Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 107 ↩︎