The Habesha people currently inhabit central and northern Ethiopia as well as the highlands of Eritrea. This article focuses on the prehistory of the habesha people by examining the hominins that lived in the region during the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras.

What is the Palaeolithic Era?

The Palaeolithic Era, also known as the Old Stone Age, is characterized by the earliest use of stone tools by our ancient human ancestors (around 2 million years ago) and is believed to have lasted until approximately 12,000 years ago. The subsequent epoch, the Neolithic or New Stone Age, began roughly 10,000 years ago, marking significant advancements in tool-making, agriculture, and societal structures1.

Ethiopia & Eritrea are considered pivotal regions in the study of human origins, believed to be the area from which anatomically modern humans first emerged2.

Even though the Paleolithic Era began approximately 2 million years ago, it remains essential to discuss earlier hominins who significantly contributed to our evolutionary history.

Ardipithecus Kadabba

In 1997, paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie discovered a fragment of a lower jaw in Ethiopia, which led to the identification of 11 specimens from at least five individuals. These findings convinced Haile-Selassie of the discovery of a new early human ancestor. Among the recovered fossils were hand and foot bones, partial arm bones, and a clavicle, dated to approximately 5.6–5.8 million years ago. Notably, one specimen, a toe bone dated to 5.2 million years old, exhibited characteristics of bipedal walking. This suggests that the ability to walk on two legs may have evolved earlier than previously believed. The environmental evidence from the site indicates these early humans inhabited areas with a mix of woodlands and grasslands, with ample access to water sources such as lakes and springs3.

In 2002, six teeth were found at the Asa Koma site in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia. The unique dental wear patterns of these fossils led Haile-Selassie, along with Gen Suwa and Tim White, to identify them as belonging to a new species named Ardipithecus Kadabba4.

The name “kadabba” means “oldest ancestor” in the Afar language.

The structure of the found toe bones, suggesting bipedal movement, might support the classification of this species as an early human ancestor, though its official classification remains subject to scientific debate, particularly because the fossil was found approximately 15 kilometres from the main site, raising questions about its direct association with Ardipithecus Kadabba.

Ardipithecus Ramidus

Between 1992 and 1994 a team led by American paleoanthropologist Tim White uncovered the first fossils of Ardipithecus ramidus in the Middle Awash area of Ethiopia. Over the years, White’s team has discovered over 100 fossil specimens attributed to this species. The name Ardipithecus ramidus reflects its foundational place in human evolutionary history, with “ramid” meaning “root” in the Afar language — signifying its proximity to the origins of humanity — and “Ardi” representing “ground” or “floor,” while “pithecus” is derived from Latinised Greek, meaning “ape”5.

The physical stature and skeletal structure of Ardipithecus ramidus offer vital clues into the life and environment of early human ancestors. The most complete specimen found, a female, was approximately 120 cm (about 3.9 feet) tall, with males only slightly larger, similar in size to modern chimpanzees. The anatomical evidence, such as features found in the upper and lower leg bones (femur and tibia), supports the notion that Ar. ramidus was capable of bipedalism, walking upright on two legs. However, their relatively flat feet without arches suggest that they were not adapted to long-distance walking or running6.

The species possessed long and powerful arms, unlike those of quadrupedal apes, which are used for weight-bearing or knuckle-walking. Instead, their finger bones were long and curving, indicating adaptations for grasping branches, pointing to a life that still involved climbing trees.

In 2009, the discovery of a partial skeleton nicknamed ‘Ardi’ added depth to our understanding of Ardipithecus ramidus.

The exact position of Ardipithecus ramidus within the human ancestral tree remains under debate. While some researchers propose that this species was ancestral to Australopithecus Afarensis — and therefore closely related to the lineage leading directly to humans — others question its exact placement.

Ardipithecus Afarensis

On the 24th of November, 1974, paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson made a groundbreaking discovery in Hadar, located in the Awash Valley of Ethiopia. He unearthed the 3.2 million-year-old remains of a hominin, which would later be named Australopithecus afarensis, famously known as “Lucy.” The name “Lucy” was inspired by the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” playing in the camp shortly before the discovery. This finding was monumental as it provided substantial insights into early human evolution7.

Researchers ultimately agreed that Lucy represented a previously undiscovered species of hominin, thus naming her Australopithecus afarensis, which translates to “southern ape from Afar.” Locally, she is referred to as “Dinqnesh,” meaning “you are marvellous” in Amharic, and the Afar people call her “Heelomali,” meaning “she is special”8.

Although no tools have been directly associated with Australopithecus afarensis, the species had hands capable of controlled use of objects, suggesting they likely used tools to some extent. Australopithecus afarensis individuals, including Lucy, probably foraged both in the tree canopy and on the ground, retreating to the trees at night to avoid predators.

Characteristics and Significance of Lucy

Lucy’s remains are currently preserved in a safe at the Paleoanthropology Laboratories of the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.

Using argon dating techniques on volcanic ash deposits found near her fossil, researchers have dated Lucy to approximately 3.18 million years old. The anatomical structure of Lucy shows a mix of human-like and ape-like characteristics. Her spine, pelvis, and knees exhibit more human-like features, while her skull, arms, and ribcage appear more similar to those of apes.

Lucy weighed about 60 pounds and was identified as a female due to her small size and the evidence of sexual dimorphism existing among hominins of her time. Her diet primarily consisted of plants, including fruits, grasses, and leaves. The discovery of Lucy was crucial for several reasons9:

- At the time of her discovery, she was the oldest and most complete hominin skeleton ever found.

- Lucy provided evidence that bipedalism evolved before the development of large, modern human-sized brains.

- Her existence supported the theory of the gradual process of human evolution.

Scientists estimate Lucy’s height to have been around 104 to 106 centimetres based on the length of her femur, while males of her species were estimated to be closer to 150 cm tall10.

Evidence supporting Lucy’s ability to walk on two legs includes several anatomical details:

- Her femur shows an angle relative to the condyle, which indicates that the leg bone was angled inward toward the knee. This inward angle helped align the center of gravity over the feet, allowing balance on one leg at a time.

- The large size of her femoral condyles suggests an adaptation to the weight distribution associated with bipedalism.

Theories on Lucy’s Death

The state of her dental development, particularly the eruption and wear of her third molars (wisdom teeth), suggests that Lucy was not a child at the time of death. Although modern human females typically develop wisdom teeth around 18 years of age, earlier humans developed faster; hence, Lucy is estimated to have been between 12 and 18 years old when she died11.

Research published in 2016, based on CT scans of Lucy’s bones, found fractures in her shoulder joint and arms that resembled those observed in humans who have fallen from significant heights. The severity of these injuries suggests internal organ damage, leading to the hypothesis that Lucy’s death resulted from falling out of a tree. However, this theory is not universally accepted, with some scientists, including Professor Donald Johanson, proposing alternative explanations, such as the possibility of Lucy being trampled by stampeding animals post-mortem12.

Australopithecus Afarensis survived for at least two million years before being succeeded by its closely related cousin, Australopithecus africanus. Australopithecus africanus made its presence known around three million years ago in the Omo region of Ethiopia.

Transition to Homo habilis

Following the era of Australopithecus africanus, the evolutionary timeline witnessed the emergence of Homo habilis. This species demonstrated a significant leap in tool-making skills, flaking stone to create knives, hand axes, choppers, and other pointed tools for both domestic use and hunting. The successful adaptation and spread of Homo habilis across most parts of savanna Africa marked a pivotal point in early human history. Approximately 1.5 million years ago, Homo habilis evolved into the more robust and intelligent Homo erectus13.

The Rise of Homo erectus

Homo erectus distinguished itself with a larger brain capacity, approximately 1,000 cubic centimetres, and a body size more than twice that of Australopithecus afarensis. This species expanded its territory from the Ethiopian regions of Harer and the Awash valley to the southwest, reaching into the Omo valley and Lake Turkana. The expansion was not limited to Africa; Homo erectus eventually crossed existing land bridges into Asia and Europe about 1 million years ago14.

Buya Eritrea

In 1995, the area around Buya in Eritrea was subject to archaeological surveys. A collaborative team comprising Eritrean and Italian paleontologists embarked on a significant journey of discovery between the years 1995 and 1997. During these explorations, they unearthed numerous fossils that provided valuable insights into human evolution.

One of the pivotal discoveries was a skull, named Madam Buya estimated to be around 1 million years old. This particular fossil exhibited characteristics indicative of both Homo erectus and Homo sapiens, representing a possible transitional form15.

Melka Kunture

Melka Kunture, located in the upper Awash Valley, approximately 50 kilometres south of Addis Ababa, is a significant archaeological site that has provided insight into the life of early humans.

Discoveries at Melka Kunture

The site has yielded numerous paleolithic findings, chronicling human activity from the early Palaeolithic through the Neolithic. Notable discoveries include16:

- In 1963, Gerard Dekker found a fossil dating back to 1.7 million years ago.

- Paleoanthropologist Jean Chavillion discovered several Homo erectus fossils aged between 1.5 and 1.7 million years.

- In 1981, a fossil of an infant jawbone, believed to be one of the earliest fossils of Homo Erectus, was discovered by Professor Margherita Mussi, dating to around 2 million years ago.

Lifestyle and Environment

The early residents of Melka Kunture were primarily hunter-gatherers, setting up camps and worksites near the water, an ideal location for hunting as animals congregated by the river. The diet predominantly consisted of meat, supported by the discovery of large quantities of animal bones, teeth, and tusks, alongside occasional hominid fossils17.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the use of fire became common around 400,000 years ago, as evidenced by unearthed hearths with scorched pebbles18. This development marks a significant evolutionary step, impacting the dietary, social, and technological aspects of early human life.

The Emergence of Modern Humans: Homo Sapiens

The evolutionary lineage continued with the emergence of Homo sapiens, first identified in the region by Richard Leakey in the Omo Kibish Formation in Ethiopia. The superior intelligence of Homo sapiens was evident in their advanced tool and weapon manufacturing techniques, signified by a brain capacity of approximately 1,300 cubic centimetres.

Omo Kibish

The Omo Kibish Formation in southwestern Ethiopia holds significant historical importance, particularly concerning the Paleolithic era. This region was characterized by its fertility and the presence of volcanic rock, which proved ideal for crafting tools. In the 1960s, archaeologists discovered two Homo sapiens fossils in this area, referred to as Omo I and Omo II. Initially, these fossils were estimated to be around 160,000 years old. However, more recent research conducted by the University of Cambridge has updated this timeline, suggesting that they are at least 230,000 years old19.

Gabi Rasu

Modern humans, classified as Homo sapiens, are known for their advanced cognitive abilities and complex social structures. Among the significant finds is a fossil discovered near Gabi Rasu in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, part of the expansive Danakil Depression. This fossil includes the skull of a man who lived between 160,000 and 154,000 years ago, marking it as one of the oldest known specimens of anatomically modern humans20.

Migration and the Development of Homo Sapiens Sapiens

Out-of-Africa Theory and Migration Routes

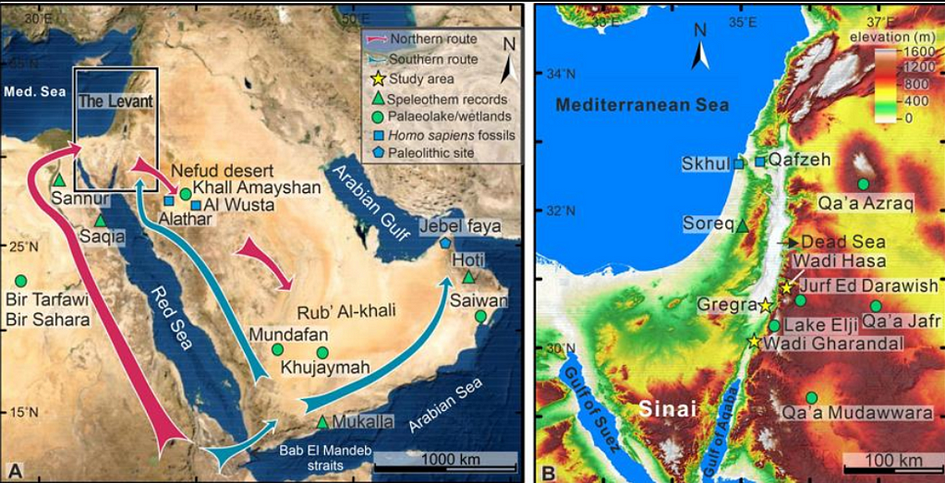

Homo sapiens sapiens, the subspecies to which all modern humans belong, are thought to descend from groups that migrated out of Africa. A key migration route was through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, a narrow passage between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. This route was pivotal for the dispersal of early modern humans out of the African continent and into other parts of the world.

Significance of the Region in Human History

Eritrea and Ethiopia have played significant roles in human history due to their geographical location and archaeological richness. The discoveries made in these regions, from the fossilized remains in Buya to the ancient hominin skulls in the Afar Depression and Awash Valley in Ethiopia, provide critical pieces of the puzzle for our understanding of our origins and migrations in the region that modern Habeshas call home.

Neolithic Era: The New Stone Age

Introduction to the Neolithic Era

The Neolithic period, also known as the New Stone Age, is a term derived from the Greek words “neo,” meaning new, and “lithos,” meaning stone. This era represents a pivotal moment in human history, marking the transition from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural communities in many parts of the world. It spans from approximately 10,000 BCE to 4,000 BCE, ending with the advent of metallurgy. The onset of agriculture during this time fundamentally changed human society, leading to the development of permanent settlements and the rise of complex societies.

The precise end of the Neolithic Era in the Ethiopian/Eritrean region remains ambiguous. Some theorists speculate that this transition occurred around the time of the Land of Punt due to the extensive documented trade between Ancient Egypt, a civilization that had entered the Bronze Age by at least the Middle Kingdom, and Punt. The exchange of metal objects, such as daggers, axes, and necklaces from Egypt to Punt during the era of Queen Hatshepsut around 1500 BCE, strongly suggests that Punt was likely a Bronze Age civilization. Consequently, I have opted to treat the history and development of Punt separtely.

Agriculture and Domestication in the Neolithic Era

During the Neolithic era, the widespread emergence of agriculture was a monumental shift in how human societies structured their lives and economies. This period saw the domestication of various plants and animals, significantly influencing dietary habits and social organization.

The diet of Neolithic inhabitants, particularly in the region now known as Ethiopia & Eritrea, is believed to have included indigenous crops such as teff, which might have been domesticated around 4000 BC21.

The domestication and cultivation of crops such as sorghum have been subjects of debate. While some researchers believe these crops were native to Ethiopia, others speculate they were imported from the Middle East. Notably, Desmond Clark suggested that wheat and barley, originally domesticated in Asia Minor and Iran, were introduced into the Nile region around 10,000 years ago. By the 6th millennium BCE, there is evidence of these crops in Egypt, spreading to southern Egypt by 4500 BCE22, and potentially moving up the Nile Valley into the Ethiopian highlands. This movement allowed for the cultivation of these grains where the climate and soil conditions were favourable.

By the third millennium BCE, the evidence from rock paintings in both Ethiopia and Eritrea and relics such as hand axes and pottery indicate an established presence of agriculture and livestock domestication. Some archaeological findings suggest that these practices could have been introduced from the Sudan up the Blue Nile Valley.

Domestication of Animals

The domestication of animals in the region predates the establishment of agriculture and permanent settlements. Livestock herding, particularly of camels, cattle, sheep, and goats, was a significant aspect of life. Camels, likely introduced from Arabia, have been attested in northern Ethiopia from about 1000 BCE. Horses, central to Ethiopian life for the past millennium, were probably introduced from the Nile Valley, originally from North Africa23.

The donkey, prevalent in the wild across the Horn of Africa, may have been domesticated independently in both Egypt and Ethiopia24.

Neolithic Art

The Quiha Rock Shelter

The Quiha Rock Shelter, situated in the Tigray Province of northern Ethiopia, was the site of excavations carried out by F. Moysey in the 1940s. An analysis by Barnett of the materials found there, which include pottery, stone tools, and animal bones — predominantly teeth from domesticated cattle and possibly from horse family animals — suggests that domesticated animals were present in the area from the earliest levels of excavation. This evidence challenges prior assumptions about when animal domestication occurred in Ethiopia, indicating that domesticated cattle might have been in the region earlier than previously thought, possibly dating back to as early as the 6th millennium BCE25

Neolithic Art in Eritrea

In Eritrea, the Neolithic period is exemplified by the presence of significant rock art, particularly in regions such as Qohaito in Southern Eritrea. These artworks, discovered in caves, primarily depict pastoralist communities and their environments. They include illustrations of animals, humans, and landscapes, showcasing the intimate relationship between these early communities and their surroundings. The primary colours used in these artworks — red, black, yellow, and white — were derived from locally available materials26.

Neolithic Artworks in Ethiopia

Tigray

Several Neolithic Artworks have also been found in Tigray, for example, three different rock art sites can be found in Northern Western Tigray: Bea’ti Shilum, Bea’ti Gae’wa and Mai Lemin27.

Central/Southern Ethiopia

The Shepe site, represents a significant archaeological and cultural location within the Sidamo Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia. Situated approximately 250 kilometres south of the capital, Addis Ababa. The Shepe site was unveiled to the world in 1965 by Fitaorari Selechi Defabatchaw, who was the governor of the Dilla district where the site is found28.

The rock art at Shepe is distinguished by its almost exclusive focus on the engravings of humpless cows.

Environmental Changes

The Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands, once densely forested, provided a conducive environment for the expansion of agricultural settlements from the fourth and third millennium BCE onward. This expansion led to increased population and a shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture and animal husbandry. The existence of old-growth forests in inaccessible locations and large trees in sacred groves indicates the earlier extensive forestation of the region. Additionally, ancient Egyptian & Greco Roman accounts of travels for ivory and animal skins hint at a once-abundant wildlife in present-day Eritrea and northeastern Ethiopia, contrasting with the sparser vegetation seen today.

Bibliography

- https://www.worldhistory.org/Paleolithic/ ↩︎

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04275-8 ↩︎

- https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/ardipithecus-kadabba ↩︎

- https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/ardipithecus-kadabba/?source=post_page—–b1be5883837c——————————– ↩︎

- https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/ardipithecus-ramidus ↩︎

- https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/ardipithecus-ramidus/?source=post_page—–b1be5883837c——————————– ↩︎

- https://iho.asu.edu/about/lucys-story ↩︎

- https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/ ↩︎

- https://iho.asu.edu/about/lucys-story ↩︎

- https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/ ↩︎

- https://iho.asu.edu/about/lucys-story ↩︎

- https://iho.asu.edu/about/lucys-story ↩︎

- A History Of Ethiopia, pg 2 ↩︎

- A History Of Ethiopia pg 2 ↩︎

- https://www.ecss-online.com/eritrea-discovery-of-new-fossil/ ↩︎

- https://www.melkakunture.it/melka-kunture.html ↩︎

- Layers of Time A History of Ethiopia: pg 8 ↩︎

- Layers of Time A History of Ethiopia: pg 8 ↩︎

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/homosapiens ↩︎

- https://newsarchive.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2003/06/11_idaltu.shtml ↩︎

- A History Of Ethiopia, pg 3 ↩︎

- Layers of Time A History of Ethiopia: pg 11 ↩︎

- Layers of Time A History of Ethiopia: pg 11 ↩︎

- https://www.science.org/content/article/single-domestication-donkeys-helped-build-empires-around-world ↩︎

- Quiha Rock Shelter, Ethiopia: Implications for Domestication ↩︎

- http://www.madote.com/2017/04/understanding-rock-art-in-eritrea.html ↩︎

- Explorations of Three Rock Art Sites in Northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia Tekle Hagos ↩︎

- https://africanrockart.britishmuseum.org/country/ethiopia/shepe/ ↩︎