The Aksumite Empire set itself apart from other contemporary empires in several ways, one such method was through its distinct craftsmanship. While the Aksumites maintained active trade with civilizations such as South Arabia, Persia, India, Sri Lanka, Egypt, and the broader Mediterranean, over 99% of the pottery discovered was locally produced1. This article serves as a brief introduction to the various types of pottery found, including cauldrons used for cooking, bowls for serving food, and cups, with nobles often using goblets. In addition to pottery, other items such as figurines, necklaces, and ornaments are also explored.

It is important to note that archaeological excavations in the Aksumite region are still in their early stages. Most of the significant work was conducted in the 20th century, with limited progress since then due to various external factors. As more excavations continue, further discoveries are anticipated. This article offers a snapshot of the Aksumite past, focusing on four sections: pottery, metal objects (gold, silver, and bronze), ivory artifacts, and a brief overview of stone objects. Stone objects will be covered more comprehensively in a separate article focused on Aksumite architecture.

Pottery

Pottery artifacts are abundant in both the pre-Aksumite and Aksumite periods. The most common type of pottery is redware, characterized by its high iron content2, although black and grey ware has also been discovered. The pottery primarily reflects indigenous elements, but influences from the Nile Valley, Southern Arabia, and the Mediterranean are also evident3. Most of these objects were used for carrying food, beverages, and storage4. However, other use cases have been found, such as the “Foot-Washer” that had an elevated platform where the feet were placed, and the bowl would then be covered with water (Probably also functioned as a method of cooling the feet), or used for when applying henna on the feet, to provide stability5. Notably, there is no evidence of a pottery wheel being used, suggesting that vessels were likely handmade6. Initially, pottery-making was a simple, domestic activity, but over time, specialized craftsmen became more prevalent7.

Redware: Pottery fired in an oxygen-rich environment, resulting in a reddish colour due to high iron oxide in the clay.

Black ware: Pottery fired in a reduced oxygen environment, creating a dark, often black surface from carbon deposits.

Grey ware: Pottery with a greyish tone achieved by firing in a partially oxygen-restricted environment, resulting in an intermediate colour between black and red.

A “Foot-Washer”, where the feet are placed and water fills the bowl. – Source: Chittick, H. N., 1974, “Excavations at Aksum, 1973-4; a Preliminary Report,” Azania IX, Plate XII

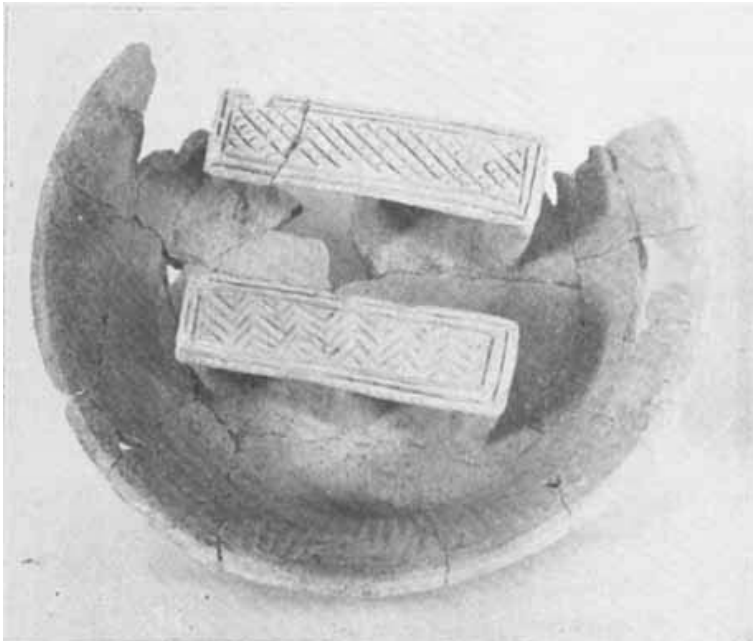

Incense Burner, found at Aksum. ‘ Tomb Of The Arches’. Source: Ancient Ethiopia, pg 66

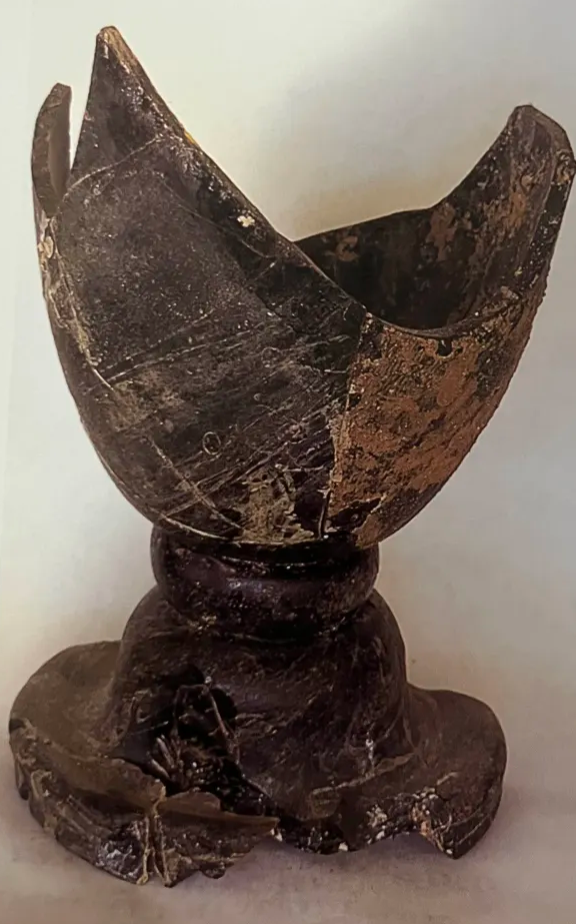

Cauldron from the late aksumite period (400AD-700AD) – Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 51

This Jar has the spout intact. Source: “Axumite Jar with Figural Spout.” 2024. Flickr. Axumite Jar With Figural Spout | In the collection of the Ar… | Flickr. October 4, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2822617017/in/photostream/.

Aksumite Jur Spout, which was once connected to a jar. The Spout is in a shape of a woman wearing a traditional hairstyle. Source: “Axumite Jar Spout.” 2024. Flickr. Axumite Jar Spout | In the collection of the Archaeological … | Flickr. October 4, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2822628227/in/photostream/.

Red-ware pottery is typically associated with the earlier phases of the Aksumite Empire, whereas brown and black wares are more commonly linked to the post-Aksumite period8. During the late Aksumite era, pottery sometimes featured symbolic designs such as crosses. Archaeologists have noted distinctions in Aksumite pottery across the empire, with variations observed between regions like Aksum and Yeha (west) compared to Matarā and Adulis (east)9. Pottery used for grain storage has been found in Aksum, along with evidence of ovens or kilns.10

Late Aksumite Elite Vessel with Cross Symbols, likely used by nobles. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 57

A Bowl with a unique arm and hands pattern found In Matara. Source: Matara: the Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea, figure 36

Large Vessel used to store grain. Les fouilles à Axoum en 1958. — Rapport préliminaire – XIIIA

An ancient furnace/klin used to heat clay. Source: Aspects de L’Archeologie Ethiopienne, figure 22

Tripod Vessel with a spout. Chittick, H. N., 1974, “Excavations at Aksum, 1973-4; a Preliminary Report,” Azania IX, Plate XII

An Aksumite Jar with unqiue patterns. Source: “Axumite Jar.” 2024. Flickr. Axumite Jar | In the collection of the Archaeological Museum… | Flickr. October 5, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2823458908/in/photostream/.

Interestingly a unique figurine of a person holding a stick was also found at adulis, the origin isn’t known, and a sculpture of a head was also found at Beta Giyorgis in Aksum.

Glass

Aksumite Goblet, likely used by nobles. Source: “Axumite Glassware, Ethiopia.” 2024. Flickr. Axumite Glassware, Ethiopia | This is part of a set of ancie… | Flickr. October 5, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2828432854/in/photostream/.

Aksumite Tile, which decorated an elite palace. Source: “Inlaid Metal Wall Tile, Axum, Ethiopia.” 2024. Flickr. Inlaid Metal Wall Tile, Axum, Ethiopia | This is one of seve… | Flickr. October 5, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2823574724/in/album-72157607017385405.

Glass artifacts from the Aksumite period have also been discovered, affirming the widespread use of glass during this era. While historians and archaeologists agree that most glass goods were likely imported, there is evidence of some local production11, particularly from the late 5th century onward. Local glassmaking may have involved recycling broken or older imported glass objects. Merchants from Egypt, the Mediterranean, Arabia, and Persia likely facilitated the trade of glassware12, however, most were from the East13. Items such as goblets, lamps, bowls, flasks, earplugs, ear studs, bracelets, and beads have been uncovered14. It is believed that objects like goblets and lamps were primarily used by the elite and nobility.

The Oldest Mitad?

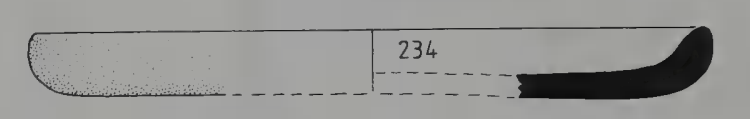

In 1987, archaeologist Richard Wilding published a study after his excavations at Aksum, where he unearthed a clay object closely resembling a mitad—a traditional Ethiopian griddle used for cooking injera. This artifact measured 19 cm in diameter and 1.8 cm in height, about half the size of a typical modern mitad15, but still remarkably similar in design. Wilding also found other similarly sized objects, but this particular one stood out as the closest match to the modern-day mitad. If this object is indeed a precursor to the mitad, it would suggest a nearly 2,000-year history of this cooking tool and potentially the method of preparing injera, a staple food in Ethiopian and Eritrean cuisine.

The relatively few mitads found, combined with the absence of direct evidence linking these artifacts to the production of teff and injera, means that it is not possible to conclusively state that injera was being eaten during the Aksumite period. While the clay objects discovered resemble modern mitads, there is no concrete proof that teff was the grain used or that these griddles were employed specifically for making injera at that time16.

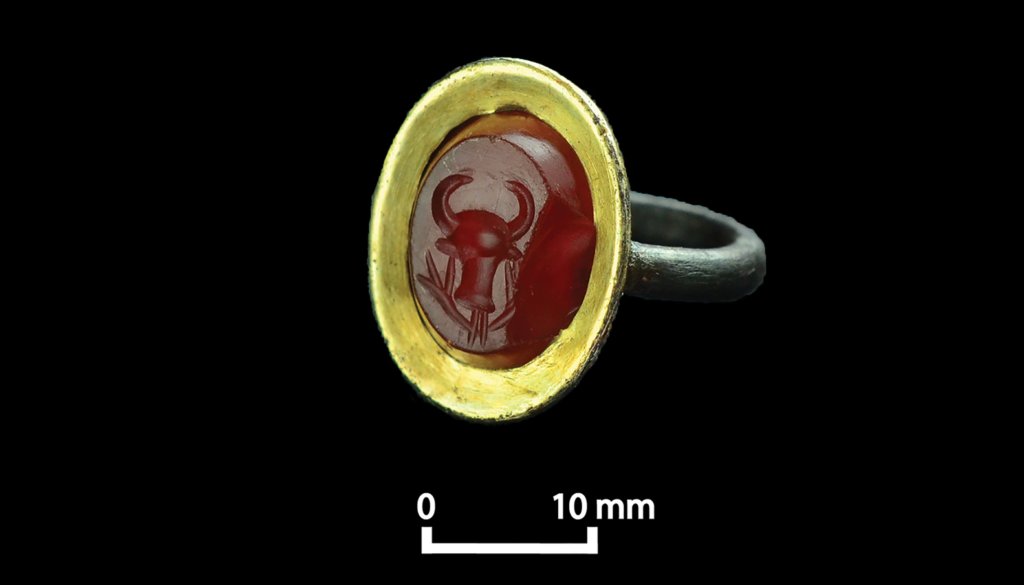

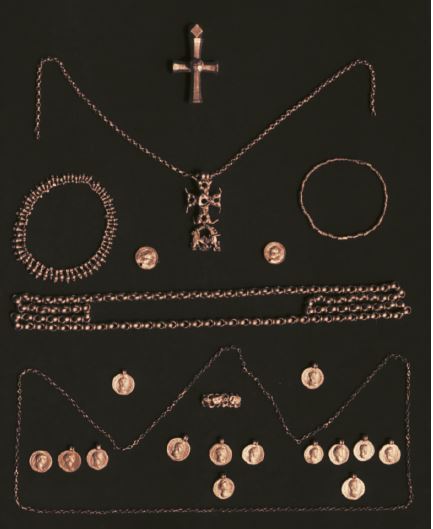

Gold, Silver & Bronze Artworks

Metals played a crucial role in the Aksumite Empire, leading to the creation of a diverse range of artifacts, such as statues, gold coins, and crosses. Archaeological and historical evidence suggests that most of these metals were sourced and processed locally17. However, due to the early stages of excavation and the difficulty in identifying mines, quarries, and smelting sites, clear evidence remains limited18. Gold was primarily used for crafting jewellery, minting coins, and decorating objects, though by the mid-fourth century, gold supplies appeared to have dwindled19, corresponding with the period after Emperor Ezana’s reign. The inscription “Mistah Werki” (“where gold is spread out to dry”) found on stone slabs indicates gold processing activities in certain regions20.

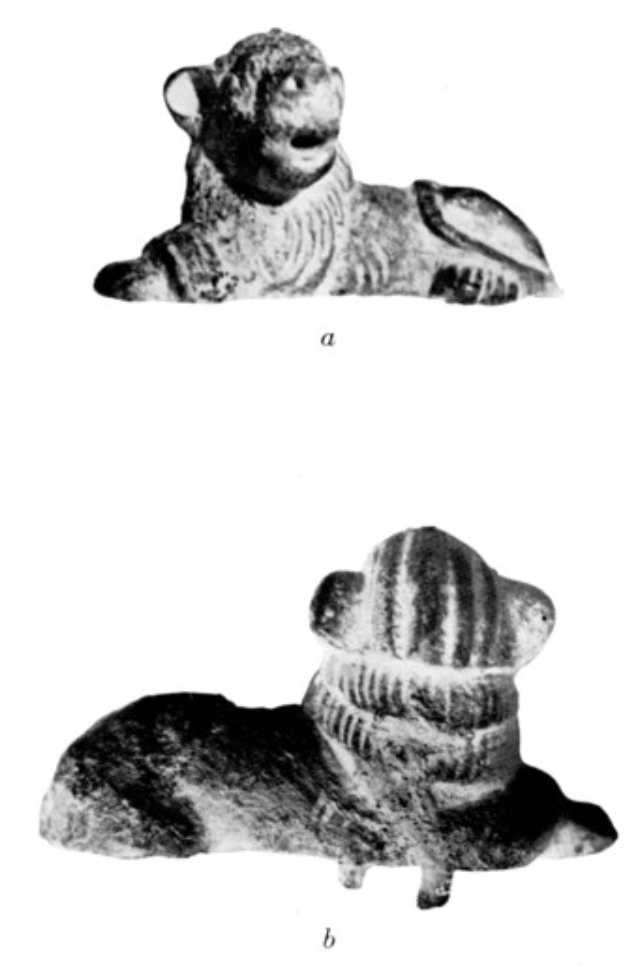

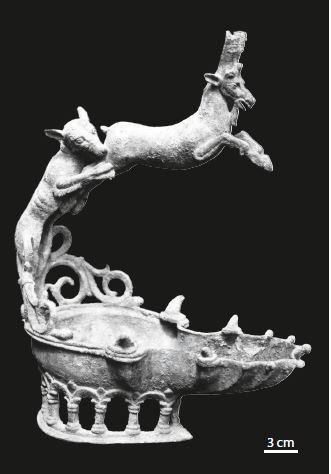

Iron was extensively used for the production of tools and weapons, including saws, hammers, knives, spears, arrowheads, hooks, and nails, all believed to have been produced locally21. While raw gold may have been mined further south, silver was mainly reserved for coinage, with few other uses. The Aksumites also had the expertise to produce alloys like bronze (copper and tin) and brass (copper and zinc), which were used to manufacture items such as lamps, mirrors, nails, hinges, handles, and hooks22. These discoveries highlight the advanced metallurgical knowledge of the Aksumite people.

Gold Jewelry Found AT Matara, Featuring a cross, braclets, necklaces, roman gold coins etc. Source: atara the Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea, pg 26

Lion Statue found in Aksum, measuring 4.9 cm in length and 2.6 cm in height. This artifact is one of the more notable bronze objects unearthed, demonstrating the skill of Aksumite craftsmen. Source: Les fouilles à Axoum en 1958. — Rapport préliminaire – Plate XIV

A Bronze Lamp found at Matara, it illustrates a sacred hunt (a symbol found in southern arabia). Source: Matara: the Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea. Figure 55b

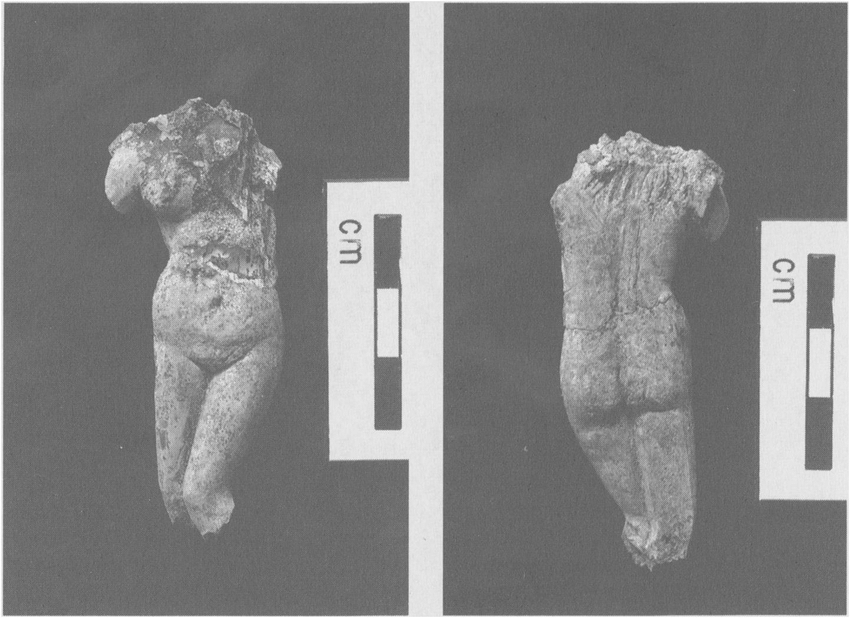

7cm tall, Bronze Statue Found at Matara, depicting a woman, created during the late Aksumite era (6th-8th century AD). Source: Aspects de L’Archeologie Ethiopienne, figure 13

Cross found in matara, with a loop at the top, where it could be attached to a chain and turned into a necklace. Source: Matara: the Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea

, Figure 18

Bronze Balance, found at Adulis used for weighing items. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 76

Weighing Instruments found at Adulis, used when calculating the price of goods. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 78

Lion Head Ornaments found at Adulis, near the church. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 79

Iron Spearheads found at Adulis. Used ontop of sticks as spears for warfare. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 82

Ivory

Ivory was another important material, not only for raw export but also for local craftsmanship. Ivory was sawn, chiselled, and carved into decorative items such as those found in the Tomb of the Brick Arches23, including representations of birds and animals. Ivory chairs and figurines have also been discovered, such as those found in the Tomb of the Brick Arches.

Ivory was among the most significant exports of the Aksumite Empire, playing a vital role in its trade networks. From the pre-Aksumite period, the port city of Adulis was notably recorded by Greco-Roman sources as a major exporter of ivory. This trade continued through to the later stages of the empire, where ivory was not only traded but also used domestically, with artifacts indicating its application in building decorations. For a deeper understanding of the role of ivory in the Aksumite trade and its importance to the empire, you can explore more in the article about Article discussing Adulis.

Ivory Panel, used as decoration in the ‘Tomb of the Brick Arches’ At Aksum. Source: Ancinet Ethiopia, Page 65.

Carveed Ivory Decoration in Aksum, ‘The fourth-century Tomb Of The Brick Arches’. Source: Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 170.

An Ivory Figurine of a woman found at Aksum at the ‘Tomb of the Brick Arches” which is dated to the late 3rd century AD. Source: Punt and Aksum: Egypt and the Horn of Africa, pg 7

Stone

Stone was likely the most extensively used material in the Aksumite Empire, owing to its abundant availability in the northern highlands of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. This natural abundance made stone the go-to resource for various construction projects, and although much of the stonework falls under the category of “architecture,” which will be covered separately, there are notable stone objects worth mentioning.

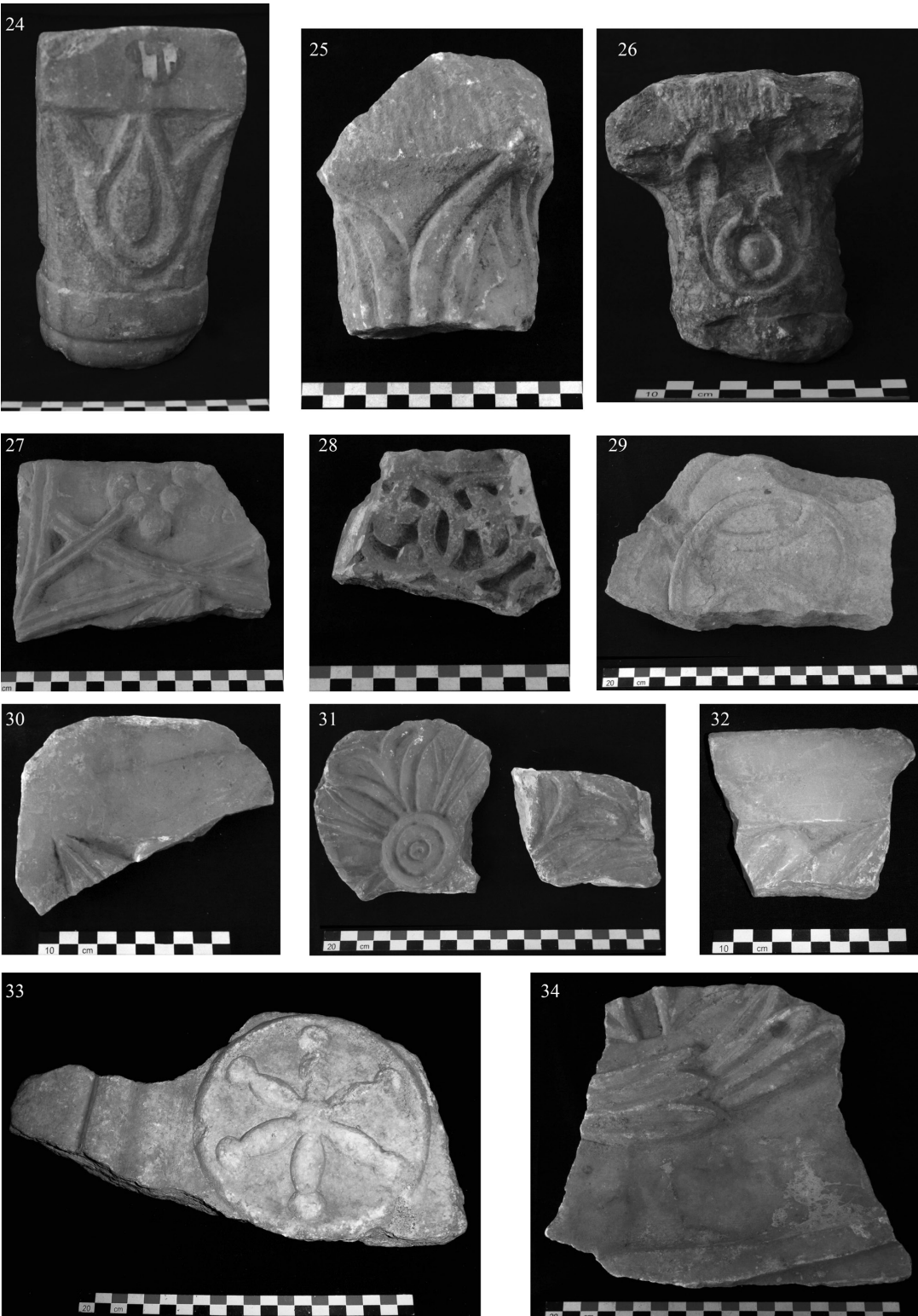

Among these are marble artifacts discovered at Adulis, which were used to adorn churches, reflecting the craftsmanship and religious significance of the time. Additionally, unique feline-headed waterspouts have been uncovered in Aksum. These intriguing pieces were likely used in elite structures, such as palaces or residences of nobles, serving both functional and decorative purposes for fountains.

Various Marble Artifacts found at Adulis. These were fragments of various objects, panels. Most are Byzantine in nature and were decortative elements for churches. Source: The ancient Red Sea port of Adulis and the Eritrean coastal region, pg 93

Feline-Headed Waterspouts, likely used to decorate a fountation. Source: “Axumite Architectural Fragments.” 2024. Flickr. Axumite Architectural Fragments | I will go out on a limb an… | Flickr. October 5, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adavey/2823506028/.

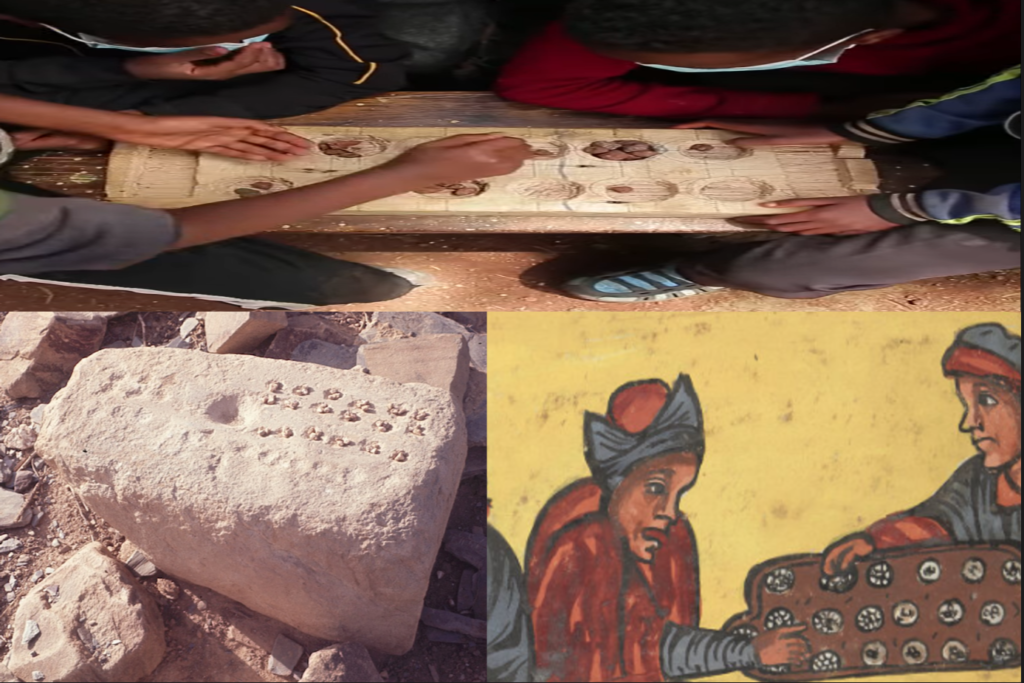

Gebeta – An Ancient Board-Game

/Or 791, f. 151v), and at the top, modern-day Ethiopian children are shown playing Gebeta (Source).

Archaeologists have uncovered stone slabs and clay boards dating back to the Aksumite period that were used to play the traditional game Gebeta (also known as Mancala)24. One significant discovery is a stone slab found in Matara, which stands as one of the oldest known boards of this game, providing evidence of around 2,000 years of Gebeta being played in both Eritrea and Ethiopia. This remarkable finding highlights the long-standing cultural significance of the game in the region. To learn more about how to play Gebeta, you can watch the instructional video here:

Excavation Reports

Bibliography

- Ancient Ethiopia, pg 75 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 233 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 159 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 161 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 235 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 159 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 161 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 234 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 234 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 235 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 162 ↩︎

- Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 239 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 162 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 165 ↩︎

- Excavations at Aksum : an account of research at the ancient Ethiopian capital directed in 1972, pg 268 ↩︎

- Excavations at Aksum : an account of research at the ancient Ethiopian capital directed in 1972, pg 308 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 165 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 165 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 165 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 166 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 166 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 167 ↩︎

- Foundations of an African Civilisation (Eastern Africa Series): Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – Ad 1300, pg 172 ↩︎

- Ancient Ethiopia, pg 30 ↩︎